This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

All

Autoblog

Autocar RSS Feed

Automotive News Breaking News Feed

Automotive World

Autos

Electric Cars Report

Jalopnik

Automotive News | AM-online

Speedhunters

The Truth About Cars

AVL: Multi-year technical partnership for hyd...

Mar 14, 2025 0

Change on Volkswagen Supervisory Board: Chris...

Mar 14, 2025 0

“This is the future of motoring!”, says Brad,...

Mar 14, 2025 0

VDA survey of medium-sized automotive compani...

Mar 14, 2025 0

All

All Stories

All Stories

BioPharma Dive - Latest News

Breaking World Pharma News

Drugs.com - Clinical Trials

Drugs.com - FDA MedWatch Alerts

Drugs.com - New Drug Approvals

Drugs.com - Pharma Industry News

FDA Press Releases RSS Feed

Federal Register: Food and Drug Administration

News and press releases

Pharmaceuticals news FT.com

PharmaTimes World News

Stat

What's new

NHS urged to offer single pill to all over-50...

Mar 9, 2025 0

Naturally occurring molecule rivals Ozempic i...

Mar 9, 2025 0

Future drugs may snap supply chain fueling br...

Mar 9, 2025 0

Researchers reveal key mechanism behind bacte...

Mar 9, 2025 0

PhV non-compliance notification contact point...

Mar 14, 2025 0

Template for late submission of ICSRs to EV

Mar 14, 2025 0

All

Breaking DefenseFull RSS Feed – Breaking Defense

DefenceTalk

Defense One - All Content

Military Space News

NATO Latest News

The Aviationist

War is Boring

War on the Rocks

How To Check Transmission Fluid Best Step By ...

Mar 4, 2025 0

NATO Secretary General meets the President of...

Feb 9, 2025 0

NATO Secretary General meets the President of...

Feb 9, 2025 0

NATO Secretary General meets the Minister of ...

Feb 9, 2025 0

Allies agree NATO’s 2025 common-funded budgets

Feb 9, 2025 0

All

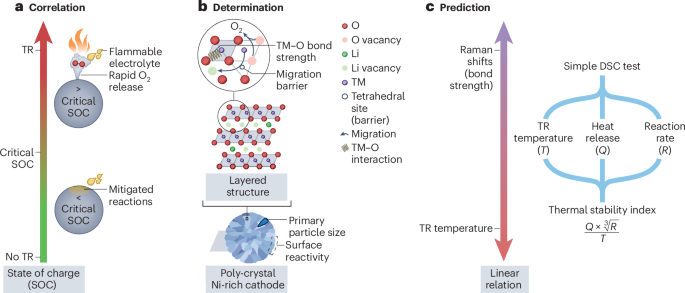

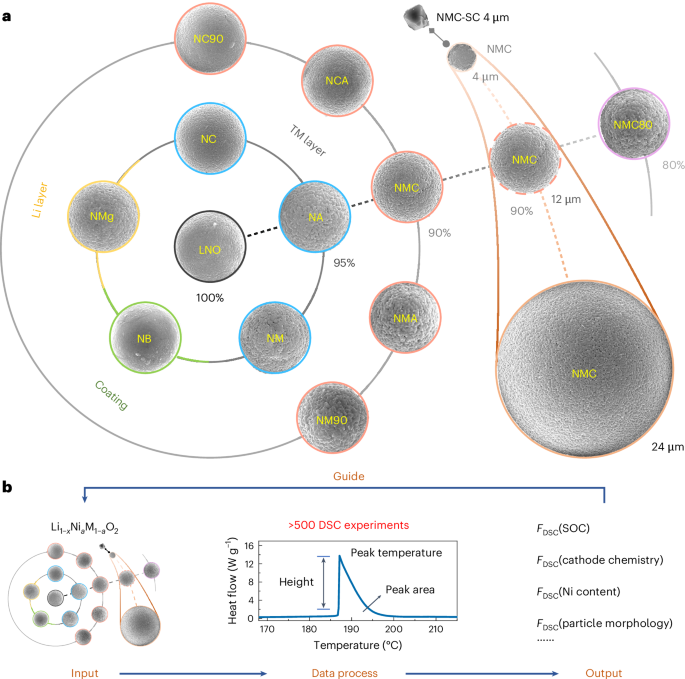

Advanced Energy Materials

CleanTechnica

Energy | FT

Energy | The Guardian

EnergyTrend

Nature Energy

NYT > Energy & Environment

PV-Tech

RSC - Energy Environ. Sci. latest articles

Utility Dive - Latest News

Postpone Interfacial Impoverishment of Zn‐Ion...

Mar 14, 2025 0

Dual‐Aspect Control of Lithium Nucleation and...

Mar 13, 2025 0

Toward Complete CO2 Electroconversion: Status...

Mar 13, 2025 0

Foldable Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells Enab...

Mar 13, 2025 0

- Contact

- Agriculture

- Automotive

- Beauty

-

Biopharma

- All

- All Stories

- All Stories

- BioPharma Dive - Latest News

- Breaking World Pharma News

- Drugs.com - Clinical Trials

- Drugs.com - FDA MedWatch Alerts

- Drugs.com - New Drug Approvals

- Drugs.com - Pharma Industry News

- FDA Press Releases RSS Feed

- Federal Register: Food and Drug Administration

- News and press releases

- Pharmaceuticals news FT.com

- PharmaTimes World News

- Stat

- What's new

- Defense

- Energy & Water

- Fashion

- Food & Beverage

- Healthcare

- Legal

- Manufacturing

- Luxury

- Medical Devices

- Mining

- Real Estate

- Retail

- Science Journals

- Transport & Logistics

- Travel & Hospitality