How Native Water Protectors Champion Water Quality

Leanna Goose grew up ricing manoomin (wild rice) as a member of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe. “Wild rice is culturally significant to Aniishinabe people here in Minnesota. It’s our connection to the land, water and our ancestors…I had a friend say that Aniishinabeg people, if we were to lose this plant, we […] The post How Native Water Protectors Champion Water Quality appeared first on Modern Farmer.

Leanna Goose grew up ricing manoomin (wild rice) as a member of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe.

“Wild rice is culturally significant to Aniishinabe people here in Minnesota. It’s our connection to the land, water and our ancestors…I had a friend say that Aniishinabeg people, if we were to lose this plant, we would lose a huge chunk of ourselves,” Goose says.

“My sister and I this past fall were finishing our rice, and I had so much respect for my ancestors and how hard that work is —to dry the rice, parch it, and winnow it—is a whole process from start to finish.”

Goose is also passing the sacred traditions on to future generations – as much as she can. Wild rice is under threat from climate impacts, unchecked pollution and overdevelopment, causing contamination, sea level rise, disruptions of freshwater wetlands and more.

TAKE ACTION

How to better support Indigenous food sovereignty initiatives.

But Native people have been the stewards of the waters in their territories for tens of thousands of years, just as we have been stewards of the land. In this second part of our two-part series, we dive deeper into some challenges of water stewardship and how Indigenous voices in regions across the continental U.S. rise to the call of Mother Àwęˀkęhaˀnęˀ (Water, Skarure) to protect her and all life dependent on water.

Saying no to pipelines

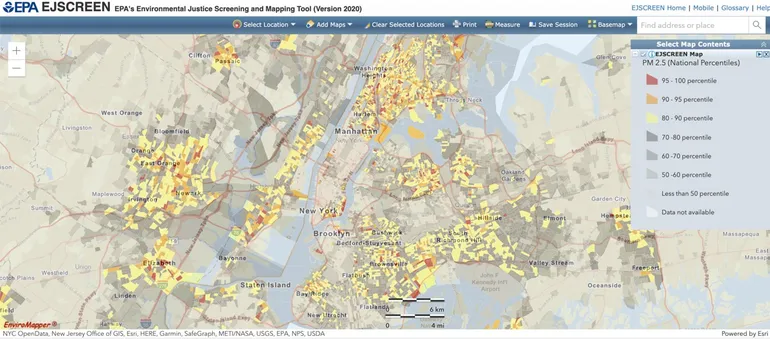

In the Great Lakes Region and Midwest, Enbridge, a Canadian-based pipeline operator in the Great Lakes, has faced controversy for decades.

Their 1960s Line 3 pipeline through the Great Lakes region caused one of the biggest inland oil spills in US history in 1991. Occurring in Grand Rapids, Minnesota, it spilled 1.7 million gallons into Prairie River – a tributary of the Mississippi.

The line weakened over time. The Minnesota Dept of Commerce reports 15 failures since 1990, resulting in more than 50 barrels of oil per incident. Corrosion and cracking prompted over 950 excavations since 2000 alone, and 10 times as many “anomalies” per mile than any other pipeline in the Mainline corridor. All told, Enbridge has since paid more than $11 million to address environmental damage from Line 3.

In 2010, they had the second largest inland oil spill, estimated at 843,000 gallons at Talmadge Creek and the Kalamazoo River, a tributary to Lake Michigan.

Ogimaa Giniw Ikwe is a citizen of Miskwaagamiiwi-Zaagaiganing (Red Lake Nation), where she’s been “deeply involved with the work of water protection and conservation and those types of things throughout Minnesota for probably the last dozen years.”

She’s not convinced that Enbridge is doing all they can to preserve wetlands, like those in Minnesota where their Line 3 pipeline runs. “In places with shifty ground, they took steel panels and drove them in so the pipeline was stabilized, and fractured a number of underground aquifers, including artesian aquifers that are not easily replaceable,” Giniw Ikwe says.

An estimated 280 million gallons of groundwater spilled from the ruptures, largely tracked and reported by environmental and Indigenous groups. Thermal imaging showing 45 spots along the pipeline where warmer groundwater appeared to surface. There were four major sites in or near tribal lands, treaty territories or wild rice lakes, from 2021 to 2023.

The water losses occurred while climate change is rapidly shifting weather patterns. Minnesota endured multi-year drought, even severe drought conditions, increasing risk of wildfires.

But the officials did not lay blame on these massive industrial leaks. There was controversy raised as officials primarily blamed farmers, claiming over-pumping of aquifer water to crops. Giniw Ikwe disagrees.

“I think that aquifer damage had a much stronger play in what’s happening,” says Giniw Ikwe.

“Then this stuff (contaminants) sinks to the bottom, damaging delicate wetlands areas, which filters out clean water and ensures water in Minnesota can trickle down into aquifer systems, and that’s where they laid this pipeline. So it’s been really contentious.”

She refers to the resulting pooling mix of breached aquifer water, drilling fluid and grout used to patch the breaches as a potential hazard to the wetlands and groundwater, even after so-called repairs.

Looking to the future

Many people across the region were deeply opposed to the installation of a new/reparative pipeline, questioning its need. And states like Michigan are still fighting in court over a cease and desist issued years prior to stop the flow entirely.

But groups are pumping out solutions as well.

Leanna Goose works as a co-facilitator and organizer for Rise and Repair, an alliance of organizations advancing legislative climate justice in Minnesota. She does research in the Protecting Manoomin for the Next Seven Generations project, which studies wildlife and addresses challenges proactively.

There are more than 17 species of wild rice indigenous to her research area listed as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. They are essential to biodiversity and support a thriving ecosystem, clean water, and human life. It’s particularly sensitive during the “floating leaf” stage, and water fluctuations can disrupt an entire rice bed.

“This past ricing season was a tough one for manoomin. A lot of the rice beds were washed out in the spring. There was a lot of precipitation, and then a drought the last part of summer,” Goose says. With Rise and Repair, Goose is advancing legislation to hopefully make future ricing seasons easier.

“We’re trying to recognize the inherent right of wild rice to exist and thrive – that all living beings have a right to be here just like we do. This legislation brings that culture of respect to all of Minnesota and creates systemic change, where we don’t just view the world around us as natural resources, but as living beings we share this earth with – as relatives.”

Beth Roach is a Nottoway tribal leader, seedkeeper, entrepreneur, and Water Protector. She’s also national campaign manager for the Sierra Club, one of the most historic grassroots environmental organizations in the country.

“For the last two years, I’ve been building a new national water conservation campaign for the Sierra Club that advances water protection under the Clean Water Act,” Roach says.

The work she does is a personal imperative as much as a professional one. She talked about the Dakota Access Oil Pipeline Protest slogan “Water is Life”, and how that moment of championing clean water rights lifted many tribal voices protecting our waters throughout Turtle Island (The Americas).

READ MORE

Meet the farmer training Indigenous youth

“We often see our ancestors, ourselves, and future generations of the earth itself, therefore we are instructed to nurture and steward these gifts as if all life depends on them,” says Roach.

“When I’m cleaning trash off shorelines and pulling tires out of the river, I have an embodied feeling that those items will not be doing harm to my waters anymore. When I’m advocating for stronger policies, I know that I’m demanding a future that we need to see. When I’m planting seeds and tending to the soil, I know that I’m doing my part to pass on this knowledge to the next generation. When I’m learning about climate adaptation strategies, I know that I’m giving the next generation a fighting chance.”

The post How Native Water Protectors Champion Water Quality appeared first on Modern Farmer.