This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

All

Autoblog

Autocar RSS Feed

Automotive News Breaking News Feed

Automotive World

Autos

Electric Cars Report

Jalopnik

Automotive News | AM-online

Speedhunters

The Truth About Cars

Aurora releases Safety Report in preparation ...

Mar 25, 2025 0

Market launch of the new Tayron: more space f...

Mar 25, 2025 0

Pioneer recognized by Toyota Motor for string...

Mar 25, 2025 0

VDA: Mobility Innovation Summit opens in Berlin

Mar 25, 2025 0

All

All Stories

All Stories

BioPharma Dive - Latest News

Breaking World Pharma News

Drugs.com - Clinical Trials

Drugs.com - FDA MedWatch Alerts

Drugs.com - New Drug Approvals

Drugs.com - Pharma Industry News

FDA Press Releases RSS Feed

Federal Register: Food and Drug Administration

News and press releases

Pharmaceuticals news FT.com

PharmaTimes World News

Stat

What's new

Keeping fit and building muscle could increas...

Mar 23, 2025 0

Continued medication important for heart fail...

Mar 23, 2025 0

All

Breaking DefenseFull RSS Feed – Breaking Defense

DefenceTalk

Defense One - All Content

Military Space News

NATO Latest News

The Aviationist

War is Boring

War on the Rocks

NATO Secretary General meets the President of...

Feb 9, 2025 0

NATO Secretary General meets the President of...

Feb 9, 2025 0

NATO Secretary General meets the Minister of ...

Feb 9, 2025 0

Allies agree NATO’s 2025 common-funded budgets

Feb 9, 2025 0

All

Advanced Energy Materials

CleanTechnica

Energy | FT

Energy | The Guardian

EnergyTrend

Nature Energy

NYT > Energy & Environment

PV-Tech

RSC - Energy Environ. Sci. latest articles

Utility Dive - Latest News

Enhanced Zinc Deposition and Dendrite Suppres...

Mar 25, 2025 0

Customized Design of R‐SO3H‐Containing Binder...

Mar 25, 2025 0

Ultralong‐Life Aqueous Ammonium‐Ion Batteries...

Mar 25, 2025 0

Synergistic Improvement of Structural Orderin...

Mar 25, 2025 0

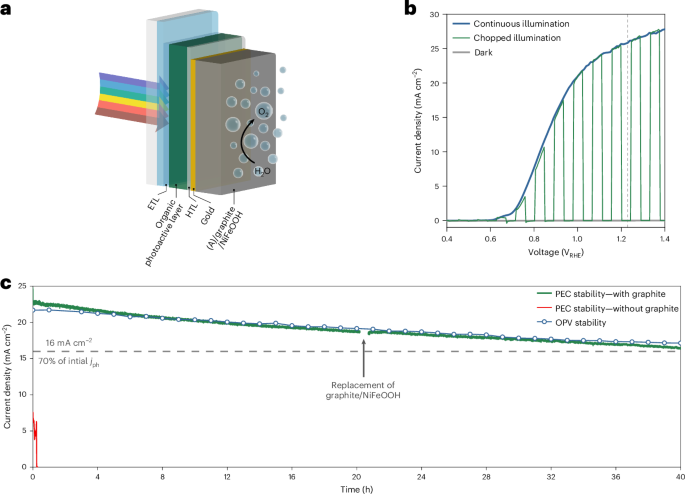

Rate matters

Mar 25, 2025 0

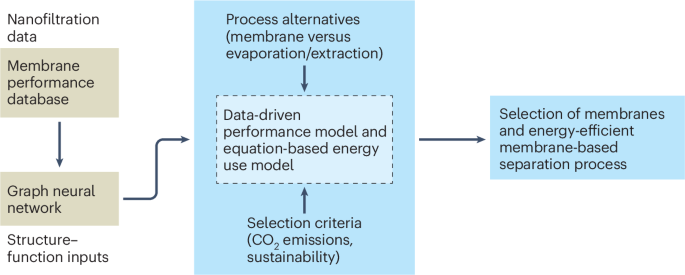

Amine oxides step up

Mar 25, 2025 0

- Contact

- Agriculture

- Automotive

- Beauty

-

Biopharma

- All

- All Stories

- All Stories

- BioPharma Dive - Latest News

- Breaking World Pharma News

- Drugs.com - Clinical Trials

- Drugs.com - FDA MedWatch Alerts

- Drugs.com - New Drug Approvals

- Drugs.com - Pharma Industry News

- FDA Press Releases RSS Feed

- Federal Register: Food and Drug Administration

- News and press releases

- Pharmaceuticals news FT.com

- PharmaTimes World News

- Stat

- What's new

- Defense

- Energy & Water

- Fashion

- Food & Beverage

- Healthcare

- Legal

- Manufacturing

- Luxury

- Medical Devices

- Mining

- Real Estate

- Retail

- Science Journals

- Transport & Logistics

- Travel & Hospitality