This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

All

Agriculture and Farming

Agriculture and Food News -- ScienceDaily

CropLife

Farming Today

Modern Farmer

National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition

How Maryland Hit Its 30x30 Goal

Apr 22, 2025 0

South Carolina Says PFAS-Contaminated Farmlan...

Apr 21, 2025 0

How Maryland Hit Its 30x30 Goal

Apr 22, 2025 0

South Carolina Says PFAS-Contaminated Farmlan...

Apr 21, 2025 0

How Trump’s Tariffs Could Hurt US Farmers and...

Apr 20, 2025 0

Strawberries Aren’t Ripe for Africa? His Farm...

Apr 20, 2025 0

The Ultimate Guide to Guest Post: Boost Your ...

Mar 8, 2025 0

All

Autoblog

Autocar RSS Feed

Automotive News Breaking News Feed

Automotive World

Autos

Electric Cars Report

Jalopnik

Automotive News | AM-online

Speedhunters

The Truth About Cars

Driving experience in a class of its own: BMW...

Apr 21, 2025 0

Hyundai Motor deploys zero-emission ELEC CITY...

Apr 21, 2025 0

Hyundai Motor Group and POSCO Group agree to ...

Apr 21, 2025 0

BorgWarner showcases electric mobility techno...

Apr 21, 2025 0

All

All Stories

All Stories

BioPharma Dive - Latest News

Breaking World Pharma News

Drugs.com - Clinical Trials

Drugs.com - FDA MedWatch Alerts

Drugs.com - New Drug Approvals

Drugs.com - Pharma Industry News

FDA Press Releases RSS Feed

Federal Register: Food and Drug Administration

News and press releases

Pharmaceuticals news FT.com

PharmaTimes World News

Stat

What's new

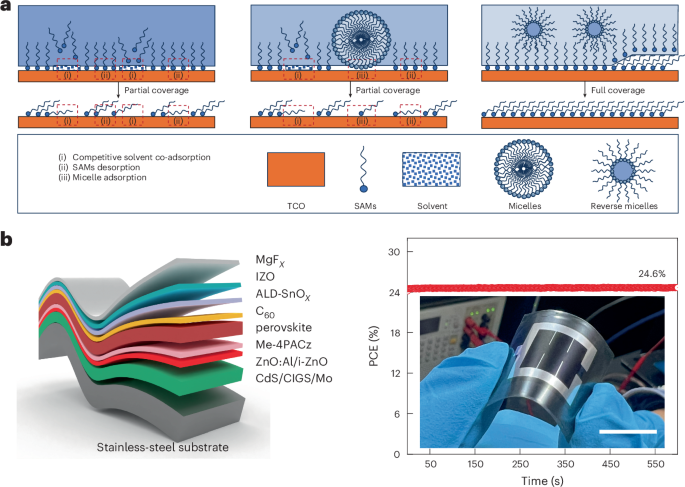

Scientists achieve record-breaking growth in ...

Apr 20, 2025 0

Popular diabetes medications, including GLP-1...

Apr 20, 2025 0

Potential treatment for Parkinson's usin...

Apr 20, 2025 0

Researchers develop an LSD analogue with pote...

Apr 20, 2025 0

All

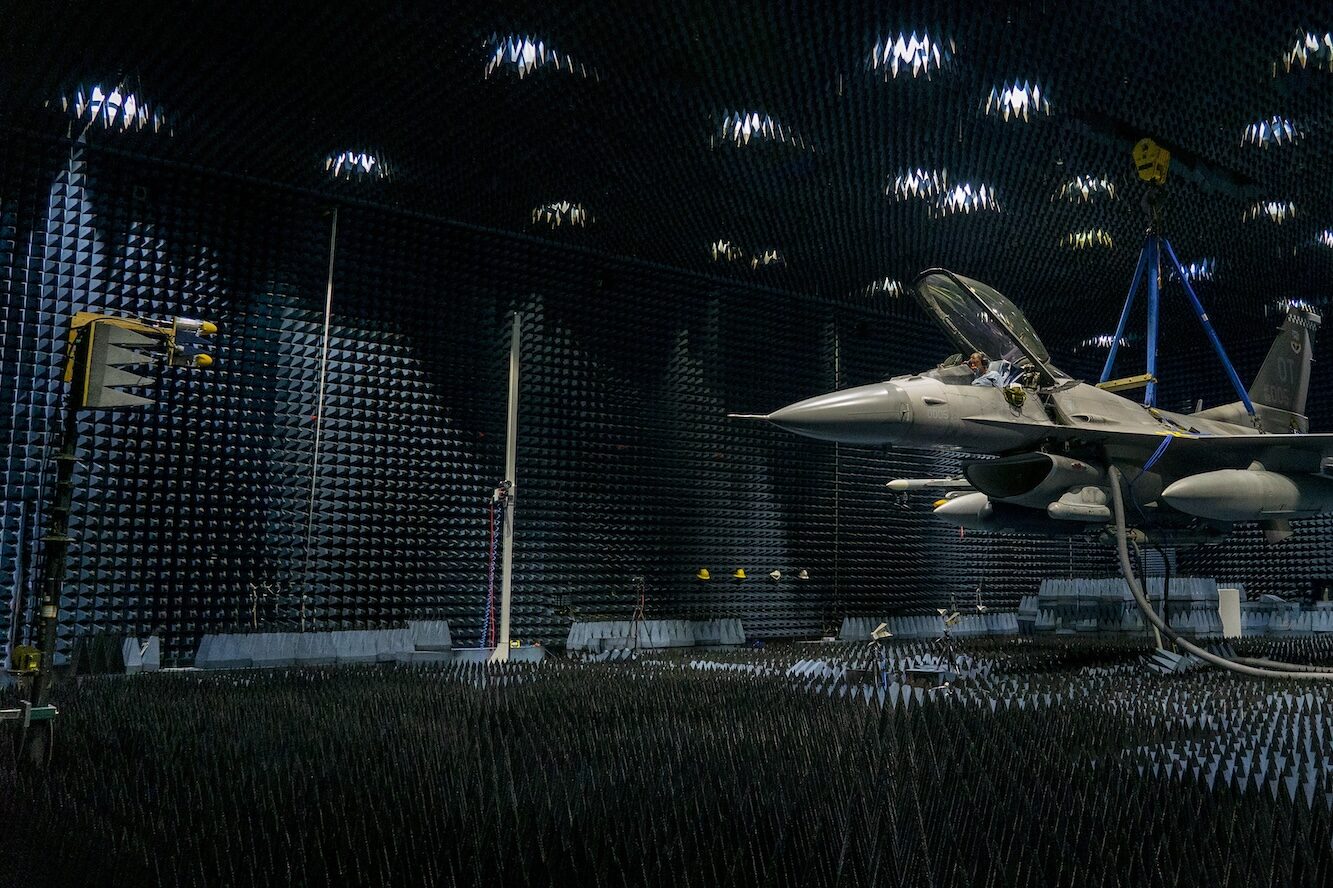

Breaking DefenseFull RSS Feed – Breaking Defense

DefenceTalk

Defense One - All Content

Military Space News

NATO Latest News

The Aviationist

War is Boring

War on the Rocks

Informal meeting of NATO Ministers of Foreign...

Apr 17, 2025 0

Ceremony to mark the 70th anniversary of Germ...

Apr 17, 2025 0

Military Committee in Chiefs of Defence Session

Apr 16, 2025 0

Joint press statement

Apr 16, 2025 0

All

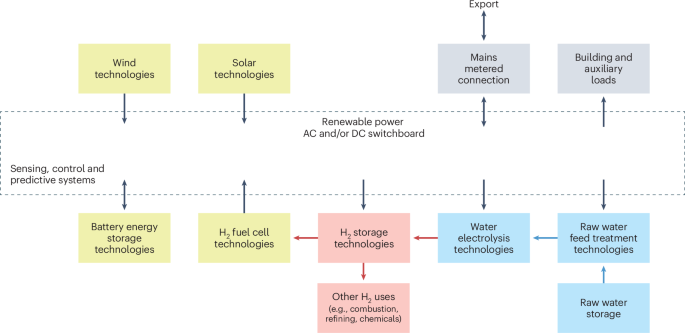

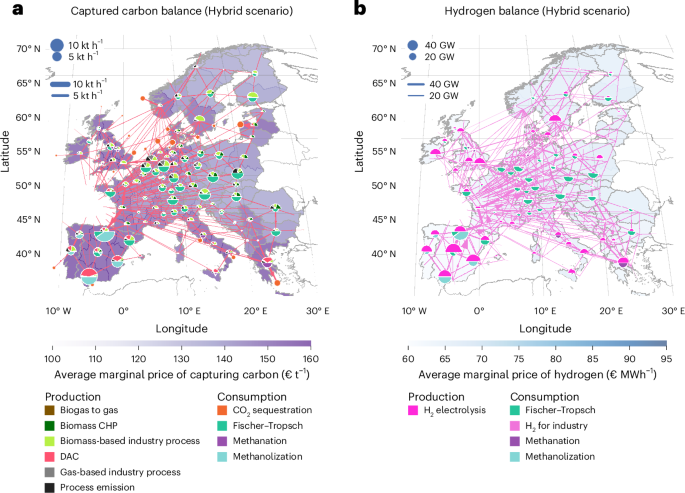

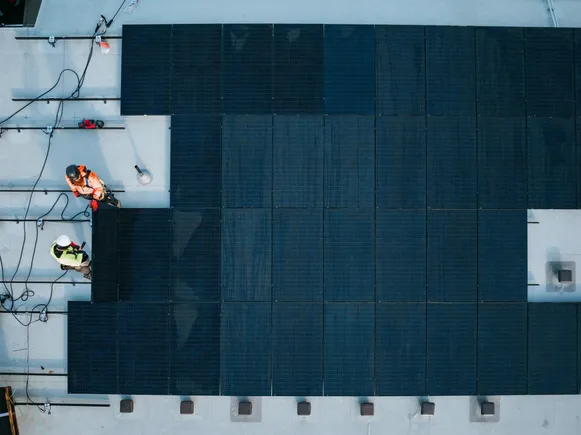

Advanced Energy Materials

CleanTechnica

Energy | FT

Energy | The Guardian

EnergyTrend

Nature Energy

NYT > Energy & Environment

PV-Tech

RSC - Energy Environ. Sci. latest articles

Utility Dive - Latest News

Streamlining Ni‐Rich LiNixMnyCozO2 Cathode Bl...

Apr 21, 2025 0

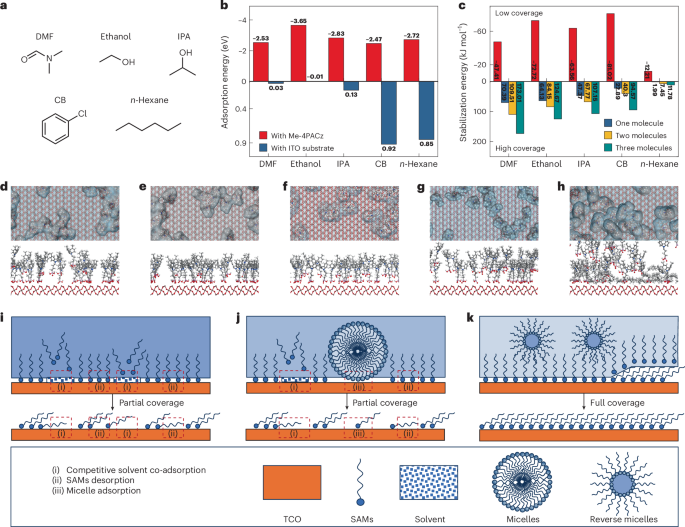

Intermediate‐Phase Homogenization Through Int...

Apr 21, 2025 0

Multivalent Dipole Interactions‐Driven Supram...

Apr 21, 2025 0

Constructing Oxygen Vacancy to Stable Anionic...

Apr 21, 2025 0

Green Solutions to Fight Louisiana Flooding

Apr 22, 2025 0

A Funeral Director Brought Wind Power to Rock...

Apr 22, 2025 0

- Contact

- Agriculture

- Automotive

- Beauty

-

Biopharma

- All

- All Stories

- All Stories

- BioPharma Dive - Latest News

- Breaking World Pharma News

- Drugs.com - Clinical Trials

- Drugs.com - FDA MedWatch Alerts

- Drugs.com - New Drug Approvals

- Drugs.com - Pharma Industry News

- FDA Press Releases RSS Feed

- Federal Register: Food and Drug Administration

- News and press releases

- Pharmaceuticals news FT.com

- PharmaTimes World News

- Stat

- What's new

- Defense

- Energy & Water

- Fashion

- Food & Beverage

- Healthcare

- Legal

- Manufacturing

- Luxury

- Medical Devices

- Mining

- Real Estate

- Retail

- Science Journals

- Transport & Logistics

- Travel & Hospitality

.jpg)