The ‘reveal and conceal game’: Air Force wargamers see value in mid-conflict deterrence

A pair of future-thinking US Air Force generals tell Breaking Defense how the service is honing its wargames to account for more nuances in combat and the unconventional use of conventional capabilities.

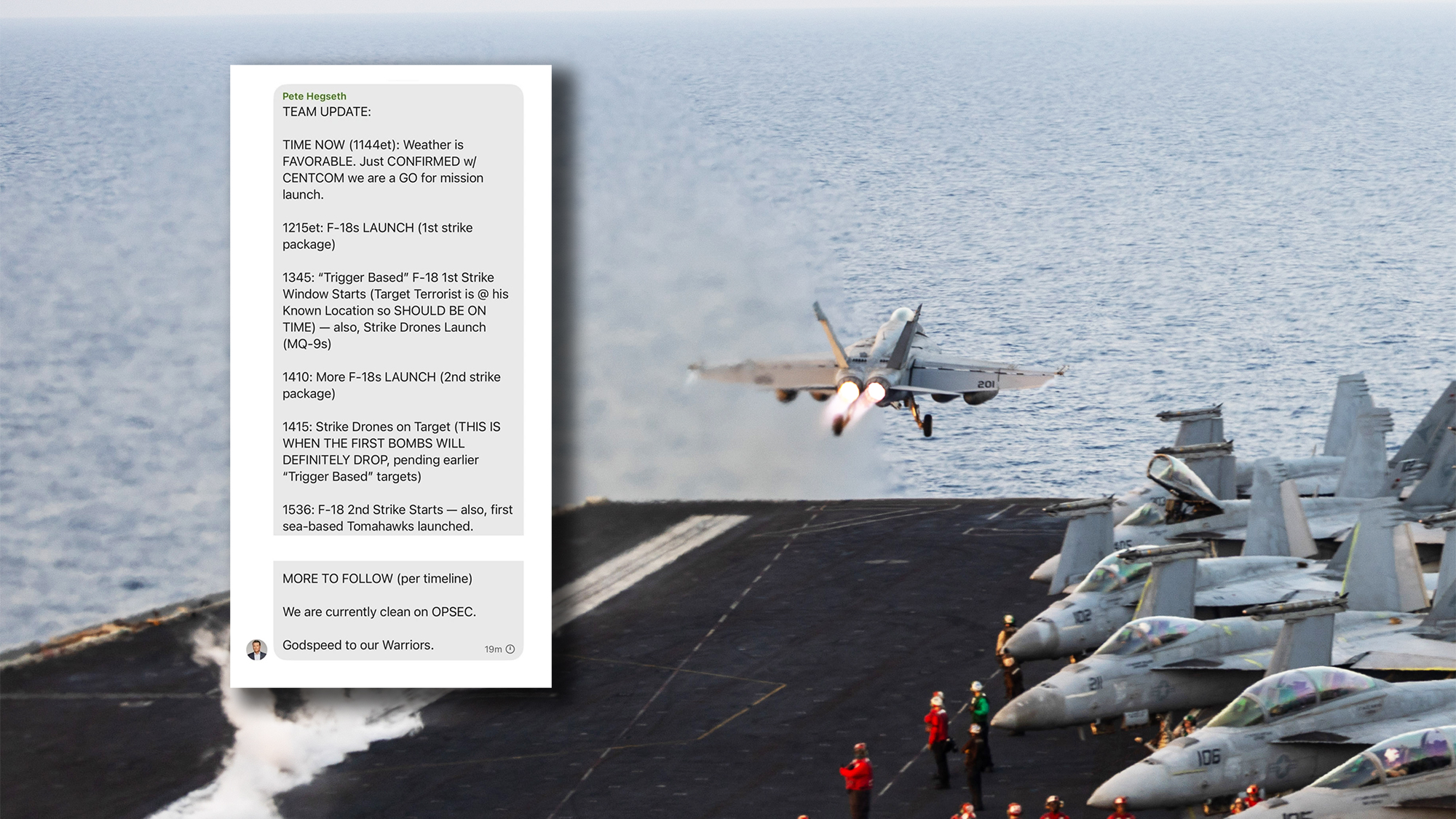

U.S. Air Force and Navy aircraft line up on the runway during an elephant walk at Kadena Air Base, Japan, Nov. 21, 2023. (U.S. Air Force photo by Airman 1st Class Tylir Meyer)

AVALON AIR SHOW — In the not-so-distant future, fears building for years have come to pass, and war has broken out in the Indo-Pacific between the US and China. Yet amid fierce fighting, the US military quickly introduces a new capability to the field — perhaps thousands of drones — and startled by the revelation, Beijing recalculates, backs down, and seeks an “off-ramp” with Washington to bring an end to the conflict.

Just such a scenario is being explored by US Air Force wargamers, who a senior officer said are investigating new uses of conventional, non-nuclear capabilities and advanced tech acquisition not just to prevent war or wage one if necessary, but to surprise an enemy so thoroughly in the course of fighting that they leave the field.

“We want to prevent wars, and that’s what America expects of us,” Maj. Gen. Joseph Kunkel, the Air Force’s director of force design, integration and wargaming, said in an interview on the sidelines of the AFA conference in Aurora, Colo, in early March. “In order to do that, in the words of [Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth], you’ve got to have the most badass military there ever was, and you’ve got to put yourself in a position where you introduce doubt into the mind of the adversary that they’re going to be successful.”

That includes even after hostilities have broken out.

Reaching for a pen and paper, Kunkel began to illustrate his point. First, he drew a steadily rising line on a graph, signifying how much adversaries study and know about US military capabilities. At a certain point, they may become confident they know enough to act. Just before that point is America’s first chance to avert conflict.

“What we want to do in this conventional deterrence is before they reach this point,” he said, pointing to a rising line on the graph, “we want to introduce something — and it’s a whole reveal and conceal game — that’s deeply troubling to them. Hey, you guys thought you had this figured out, but you know, did you ever think of that? All these problems you thought you solved, they are no longer solved.”

But even if the US is unsuccessful in deterring an adversary from beginning hostilities, that doesn’t mean the approach is no longer valid.

“Once we get into conflict, we’ve got to continue to do the same thing, where we provide them off-ramps, where we continue to give them tough problems, which is different from what we’ve done before,” he added. “How are we playing that in war games, and how are we introducing that in war games? The closest thing we’re getting to is we’re finding ways to create off-ramps” that would encourage an adversary to stop fighting.”

RELATED: A ‘bloody mess’ with ‘terrible loss of life’: How a China-US conflict over Taiwan could play out

Kunkel used his own experience flying sorties during Operation Allied Force, NATO’s military intervention in Yugoslavia in the late 1990s, as a counter-example.

“On day one, the capabilities we started out with were GBU-24, Paveway III laser-guided bombs, the most advanced bombs ever. … We were using those for about the first three weeks,” he said. Then as the war continued, pilots would go to their jets and find decreasingly precise munitions, eventually down to dumb bombs.

“Instead of our capabilities increasing as we fought, they decreased,” he said. “If you’re going to continue to give the adversary dilemmas, your capabilities have got to increase.”

That’s where, he said, an aggressive “innovation pipeline” comes into play that can feed the US military not only the capabilities it needs to fight that day, but to provide advanced tech in such numbers that the enemy is always having to rethink its odds.

Wargaming With Asymmetry, And Working Backwards

Speaking in a separate interview at AFA, Lt. Gen. David Harris said the service is honing wargames in another way: reflecting the greater “asymmetric” advantages America enjoys, listing capabilities all the way up in space down to undersea depths.

“Where do we have a competitive edge?” Harris asked. “I think that when you start looking at where we are in space, when you start looking at some of the things we see in undersea warfare, when we start looking at the developments that we’re doing in the air and space domains together, combining those, there’s something to this deterrence piece.

“I think [those are] an important part of the equation that we need to start adding into the war games,” he said.

Another recent tweak on war games, he added, comes in the form of “excursions,” essentially a data-driven deep dive into particular elements of a game to assess underlying assumptions. For example, in the event the service finds itself in an unfavorable condition, wargamers can work upstream to prevent the conditions from arising in the first place.

“It’s like playing chess,” Harris explained, where a wrong move might result in an event like an unnecessary sacrifice of a piece. “How do I unwind that and watch the tapes like football players would do, and then go back to make sure that I don’t make that move in the future?”

RELATED: As Air Force lays out Force Design, top strategist warns service is ‘underfunded’ to face China

An adversary’s economic conditions, Harris added, should also play a role in thinking about how to build a military force.

“When you put the studies together about where the adversaries are going from an economic point of view and where we go from a military point of view about what capabilities [are needed], you can’t just separate those out, they do connect,” he said.

And like Kunkel, Harris said deterrence will play a large part in a new Force Design he’s helped spearhead for the service.

“When you talk about rebuilding the military and what you need, I now have a framework,” Harris said of the new Force Design. “The fact that we’re adding in this deterrence piece of it, and what are the things that we need to continue doing? What are the things that we need to probably avoid conflict in the first place? That’s the reestablishing deterrence part of that. So in those two areas, I think we’re good.

“I think the how we rebuild the military, what capabilities are needed,” he continued, “that’s one where we have to have a conversation with the new administration and get their ideas about, how do you see the threat, what’s important to you?”

.jpg)