Inside the lab where BMW is making EVs even quieter

The German marque has installed all kinds of high-tech sound testing gear in Munich With the shift to EVs and their near-silent drivetrains, the pressure to scrutinise noise generation from wind, tyres and vibration is getting even stronger, especially for premium manufacturers. BMW recently opened a new test facility called the Aeroacoustics and Electric Drive Centre (AEC) to replace its acoustic wind tunnel, which is almost 40 years old. Located at the BMW Group Research and Innovation Centre (the FIZ) in Munich, the new facility follows the addition of the Environmental Test Centre to the FIZ back in 2010. Geared up for the fast development of electric vehicle drivetrains, the AEC consists of two parts. One is multifunctional, housing workshops for prototype work and testing equipment, the other an aeroacoustic wind tunnel, which is claimed to be the quietest and largest in the world, at 100m long, 45m high and 25m wide. Not surprisingly, designing a wind tunnel to be capable of measuring the noise levels of and in cars that are already intrinsically quiet poses challenges not just in terms of the equipment used but in the construction too. The two buildings were built in a giant pit to decouple them from the surrounding area, with a 3m-thick fl oor slab and a sound-insulated façade to isolate them from external noise and vibration. The buildings are partially separated from each other, with the second building (which BMW likens to a “semi-detached house”) housing workshops, testing and measurement stands and prototype assembly lines. This section occupies 15,000 square metres over several floors, with a further 800 square metres set aside for manufacturing future inverters in cleanroom conditions. The main test chamber has a background noise level of 54.3dBA with a car travelling at the equivalent of 87mph on the built-in rolling road, which BMW describes as the equivalent of speaking in hushed tones or the noise made by a quiet air-conditioning system. With intrusive noise being at such low levels, measuring the noise of headwind accurately is much more precise. The maximum wind speed the tunnel can generate is 155mph, thanks to a 4.5MW blower, which at that speed is moving 100,000 cubic metres of air through the tunnel every minute. The chamber is rated as an acoustic semi-free-fi eld space, meaning none of the surfaces apart from the floor reflects any sound at all. One of the latest gadgets used to measure sound is a 216-microphone ‘acoustic camera’ that can pinpoint the source of a sound to within a centimetre. The wind tunnel also has a laser vibrometry system for measuring mechanical vibration of the entire vehicle surface using laser light rather than mechanical contact. Cars can be acoustically tested while stationary or while running on a fourwheel-drive rolling road dynamometer, with or without wind in both cases.

The German marque has installed all kinds of high-tech sound testing gear in Munich

The German marque has installed all kinds of high-tech sound testing gear in Munich

With the shift to EVs and their near-silent drivetrains, the pressure to scrutinise noise generation from wind, tyres and vibration is getting even stronger, especially for premium manufacturers.

BMW recently opened a new test facility called the Aeroacoustics and Electric Drive Centre (AEC) to replace its acoustic wind tunnel, which is almost 40 years old.

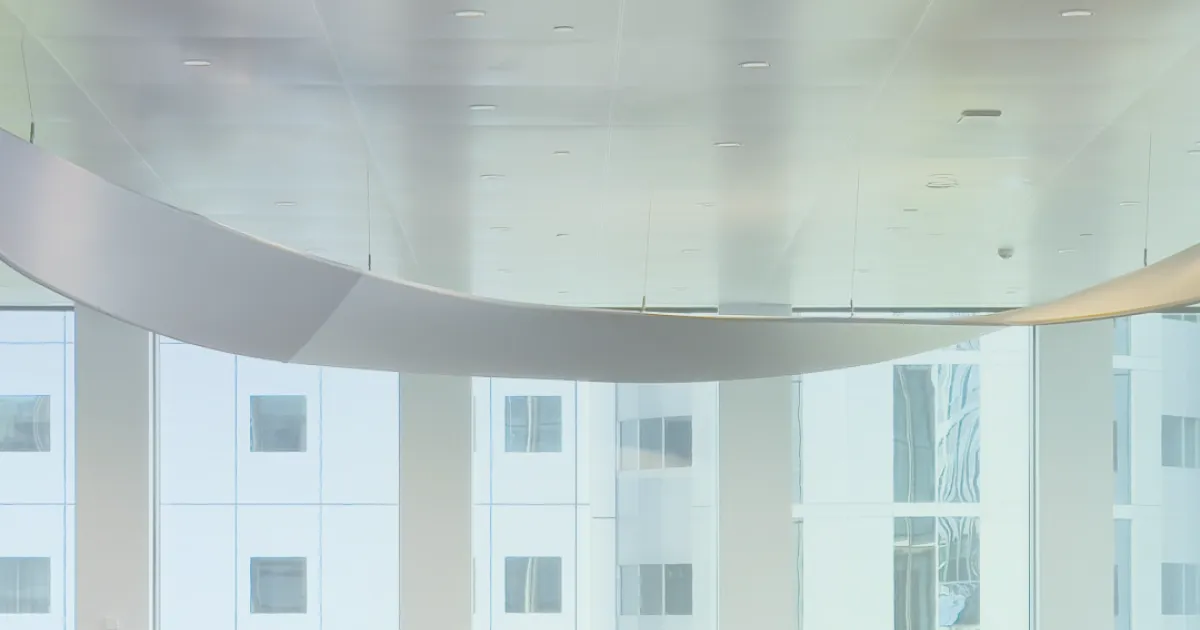

Located at the BMW Group Research and Innovation Centre (the FIZ) in Munich, the new facility follows the addition of the Environmental Test Centre to the FIZ back in 2010.

Geared up for the fast development of electric vehicle drivetrains, the AEC consists of two parts.

One is multifunctional, housing workshops for prototype work and testing equipment, the other an aeroacoustic wind tunnel, which is claimed to be the quietest and largest in the world, at 100m long, 45m high and 25m wide.

Not surprisingly, designing a wind tunnel to be capable of measuring the noise levels of and in cars that are already intrinsically quiet poses challenges not just in terms of the equipment used but in the construction too.

The two buildings were built in a giant pit to decouple them from the surrounding area, with a 3m-thick fl oor slab and a sound-insulated façade to isolate them from external noise and vibration.

The buildings are partially separated from each other, with the second building (which BMW likens to a “semi-detached house”) housing workshops, testing and measurement stands and prototype assembly lines.

This section occupies 15,000 square metres over several floors, with a further 800 square metres set aside for manufacturing future inverters in cleanroom conditions.

The main test chamber has a background noise level of 54.3dBA with a car travelling at the equivalent of 87mph on the built-in rolling road, which BMW describes as the equivalent of speaking in hushed tones or the noise made by a quiet air-conditioning system.

With intrusive noise being at such low levels, measuring the noise of headwind accurately is much more precise.

The maximum wind speed the tunnel can generate is 155mph, thanks to a 4.5MW blower, which at that speed is moving 100,000 cubic metres of air through the tunnel every minute.

The chamber is rated as an acoustic semi-free-fi eld space, meaning none of the surfaces apart from the floor reflects any sound at all.

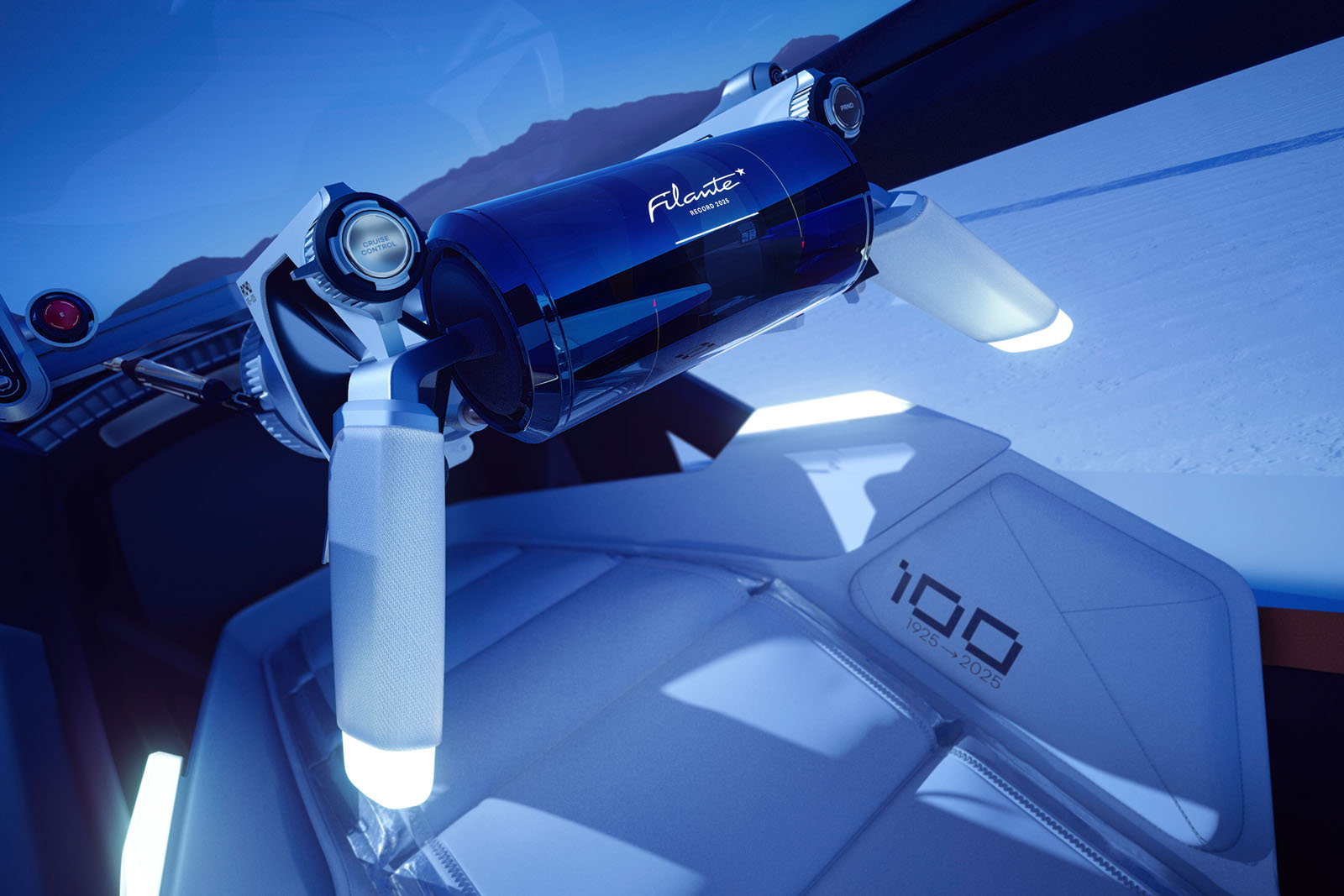

One of the latest gadgets used to measure sound is a 216-microphone ‘acoustic camera’ that can pinpoint the source of a sound to within a centimetre.

The wind tunnel also has a laser vibrometry system for measuring mechanical vibration of the entire vehicle surface using laser light rather than mechanical contact.

Cars can be acoustically tested while stationary or while running on a fourwheel-drive rolling road dynamometer, with or without wind in both cases.

.jpg)