A Chilean Pinot Noir made from grapes grown by indigenous Mapuche communities is launching in the UK after ten years of hard graft, lost vintages and cultural differences, writes Sarah Neish. But can it sell?

Changing entrenched beliefs held by a community following generations of exploitation and land theft was never going to be quick or easy work. But Chilean wine company

Viña San Pedro (VSPT), which counts Altair, Leyda and Graffigna among its portfolio of brands, was in it for the long haul when it launched the Tayu project in 2015 in the Malleco Valley, southern Chile.

Since then Tayu has seen more ups and downs than an electric seesaw, and there have been many eye-openers along the way. But ten years later, the product is finally ready to be exported to markets outside Chile, starting with the UK.

So what exactly is Tayu? A collaboration between VSPT and Chile's indigenous Mapuche communities, the project sees Mapuche families plant and tend their own vineyards before selling their grapes to VSPT in order to make a wine from one of the country's most exciting regions for Pinot Noir.

Starting with just two Mapuche families, today the partnership has grown to 11 families cultivating 30ha in Malleco, known for its red granitic soils.

“Everyone is profiting now,” Rachael Pogmore, South America buyer for Tayu's UK importer Enotria & Coe, tells

db. "And the wine has consistency year on year."

Rocky road

It's been a winding path to get here though, and one could have been forgiven for thinking Tayu might not have survived past infancy.

The ethos behind the project was a sound one. VSPT was keen to explore new terroirs, while the Mapuche, which occupy a pocket of Chile with the potential to make exceptional wine, often live in poor communities with little chance to create long-term financial stability. Offering families the opportunity to establish and run a vineyard as their own business could help provide that security for years to come.

But the dialogue wasn't quite so smooth as all that.

Firstly, the Mapuche, which make up about 8% of the current Chilean population, have historically been "agricultural-based rather than viticultural-based," says Ali Cooper MW, who lived in Chile for four years (2002-2006). Speaking at the UK launch of Tayu's 2022 vintage, he explains that while they were experts at tending the land, the Mapuche did not necessarily have the knowledge to cultivate grapes.

The concept of pruning was alien, and suggestions made by VSPT's viticulturists to crop the vines went down like a lead balloon as the advice contradicted deeply held Mapuche values about not wasting the fruits of the land.

"It was a learning and an exchange of ways of seeing the land," says Pogmore diplomatically.

Cultivating vineyards in Malleco also proved technically challenging "because to make wine outside of the easy reach of Santiago is not simple, from getting tools and equipment down there to bringing the grapes back up," Pogmore explains.

A helping hand

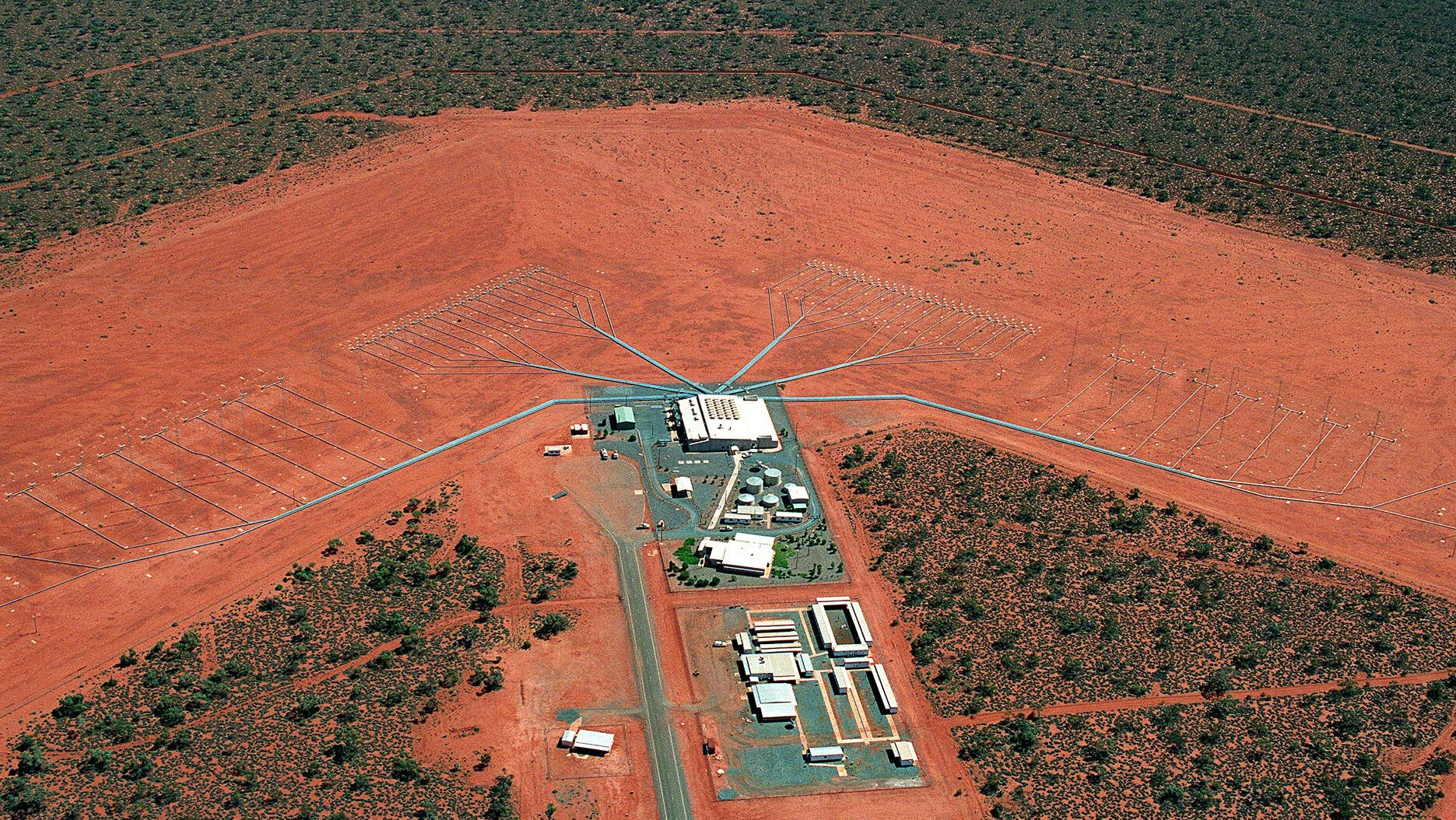

The Chilean government and National Irrigation Commission also had to be drafted in to help Tayu winegrowers fight their biggest threat: frost. Despite having a continental climate, vineyards in Malleco can see as many as 10 frosts per year, and about 1,200mm of rain (more than Bordeaux at 950mm). After some requisite hoop jumping, aspersion irrigation was eventually installed in the region, which according to Cooper "is one of the only ways of saving the crop."

"You need to consistently have water hitting the bud because you get latent heat from that. So you need a constant shower of water when the temperature is below zero," he says.

With yields already low, any loss of crop can make a big difference here. "There are only around 90ha planted in Malleco in total so it's unlikely to ever become a big commercial region because it's tricky to grow here," says Cooper. "But that's what makes it so exciting. It gets very warm in Jan and Feb, then very cool very quickly in March and April, meaning Malleco has a long ripening season, which is good news for Pinot."

The low yields too, are ideal for the concentration that this capricious red variety needs to shine.

Trust issues

Beyond the practicalities of growing grapes in Malleco and training up rookie viticulturists, there was also an undercurrent of suspicion from the Mapuche regarding VSPT's intentions for the partnership. The root cause stretches back almost two centuries.

Until the founding of the Chilean Republic in 1818, the Mapuche had been known as a fearsome warrior community which had halted the march of the Spanish conquistadors. "When the Spanish arrived in Chile in 1537 they conquered their way south until they got as far down as the Mapuche territories, where they found they could go no further," explains Cooper. "The disparate nature of the Mapuche made it difficult to conquer the area because they didn't have one joined up community." This logistical spiderweb led to a ceasefire by the Spanish in 1686, meaning southern Chile remained Mapuche heartland for many years.

However when the Chilean Republic was founded 132 years later, the government formed borders in the south, and the Mapuche became marginalised.

"They were put onto reservations, their land taken and auctioned off to large land owners in the 1930s," says Cooper. "At one point the Socialist government made moves towards giving them back their land, but then Pinochet put paid to that."

According to Pogmore it has "taken years to build the trust [with VSPT]" because of the constant uphill struggles the Mapuche have endured.

"There's a certain amount of scepticism with any big company coming in, and lots of transparency required," she says.

Both ways

The trust issues went both ways. For VSPT, investing in the Mapuche was a sizeable commitment, with the company agreeing to pre-finance the families from the planting of vines right the way through to harvest, as well as provide technical expertise and training over a 10-year period.

"There was an element of 'what happens if the Mapuche decide they don’t want to do this anymore?'" reveals Pogmore.

Ultimately, two factors proved to be gamechangers, fair payment and autonomy. Mapuche families were offered a good price for their grapes, and a 10-year partnership model "which meant they could exit the partnership down the line if they wished," says Pogmore.

The name Tayu was coined, which means "ours", and the first harvest took place in 2018.

Forest fires

Then just as the project was getting off the ground, and more families gradually felt confident enough to join the partnership, southern Chile was

hit by ferocious forest fires in 2023.

This was not only a physical loss (it sadly wasn't possible to produce a 2023 vintage of Tayu due to smoke taint) but also a spiritual one as the fires represented something deeper for the Mapuche. When their native land was stolen by the Republic, it was largely replanted with pine or eucalyptus trees. "Forestry is a polemic issue in southern Chile, with devastating forest fires caused by the monoculture approach," says Cooper, who describes the Mapuche as "incredibly earth-driven, spiritual people, with a deep-rooted connection to the forests and the soil."

Upholding its end of the deal, VSPT paid the Mapuche for their 2023 grapes but decided that for quality reasons it would not make a wine that year. The lost vintage means that while Tayu 2022 has just arrived in the UK market, from there it will switch straight to the 2024 vintage.

Tayu as a commercial product

VSPT has independent retailers and the on-trade in its sights for Tayu 2022, where the wine will be priced at about £30 and £45+respectively.

Tayu "requires a hand sell," says Pogmore. "Because of the low yields and volumes of the wine, we wouldn’t be able to get the Pinot Noir into stores on a commercial scale."

It's a shame because this 13.5% wine has the promise to bewitch everyone from connoisseurs to the masses. A lighter, fresher, more savoury style than the fruit-driven Pinots from Casablanca, there's thyme, sage and mint alongside cherries and an earthiness and racy acidity, which would pair beautifully with duck, lamb or venison dishes, and a host of other cuisines. Around 35% is whole cluster, only native yeasts are used and the wine is aged for 11 months in a mixture of concrete, stainless steel, French oak and untoasted foudre in VSPT's Maipo winery.

Its narrative is pure catnip for somms. After all, if terroir is made up not just of soils but of the people who have tended the land for generations, then Tayu is the ultimate expression of the Malleco Valley. It also challenges misconceptions about Chile, and encourages consumers to engage with the country beyond Cabernet Sauvignon.

"Chile has sometimes lacked a bit of a story, it struggles with its identity," says Cooper. "Back in 2006 I thought Chile wasn’t capable of making really good Pinot Noir. Now I know it can make exceptional Pinot, with real regionality. I think this is what Chile needs."

What's next?

According to VSPT it now plans to cast the net wider in terms of inviting more Mapuche families to join the Tayu fold. "The stretch within this particular community is maximised now, so we will be looking to expand our reach into other communities in the region," says Marcela Burgos Abad, premium sales manager for VSPT.

The families currently involved signed a 10-year contract in 2015 and had to choose this year whether to sell their grapes to rival company Concha y Toro or stick with VSPT. "They chose us. So that’s the beauty of empowering people," says Burgos Abad.

While the Tayu project is exclusively based around Pinot Noir at present, the Malleco Valley is showing strong potential for Chardonnay, with VSPT "likely to make Chardonnay plantings here in the future," says Pogmore, hinting that there may be room for Tayu's portfolio to expand.

With the low yields and limited production of Tayu Pinot Noir, the challenge may be how to cater to demand if the UK, and other markets, fall in love with it.

Changing entrenched beliefs held by a community following generations of exploitation and land theft was never going to be quick or easy work. But Chilean wine company Viña San Pedro (VSPT), which counts Altair, Leyda and Graffigna among its portfolio of brands, was in it for the long haul when it launched the Tayu project in 2015 in the Malleco Valley, southern Chile.

Since then Tayu has seen more ups and downs than an electric seesaw, and there have been many eye-openers along the way. But ten years later, the product is finally ready to be exported to markets outside Chile, starting with the UK.

So what exactly is Tayu? A collaboration between VSPT and Chile's indigenous Mapuche communities, the project sees Mapuche families plant and tend their own vineyards before selling their grapes to VSPT in order to make a wine from one of the country's most exciting regions for Pinot Noir.

Starting with just two Mapuche families, today the partnership has grown to 11 families cultivating 30ha in Malleco, known for its red granitic soils.

“Everyone is profiting now,” Rachael Pogmore, South America buyer for Tayu's UK importer Enotria & Coe, tells db. "And the wine has consistency year on year."

Changing entrenched beliefs held by a community following generations of exploitation and land theft was never going to be quick or easy work. But Chilean wine company Viña San Pedro (VSPT), which counts Altair, Leyda and Graffigna among its portfolio of brands, was in it for the long haul when it launched the Tayu project in 2015 in the Malleco Valley, southern Chile.

Since then Tayu has seen more ups and downs than an electric seesaw, and there have been many eye-openers along the way. But ten years later, the product is finally ready to be exported to markets outside Chile, starting with the UK.

So what exactly is Tayu? A collaboration between VSPT and Chile's indigenous Mapuche communities, the project sees Mapuche families plant and tend their own vineyards before selling their grapes to VSPT in order to make a wine from one of the country's most exciting regions for Pinot Noir.

Starting with just two Mapuche families, today the partnership has grown to 11 families cultivating 30ha in Malleco, known for its red granitic soils.

“Everyone is profiting now,” Rachael Pogmore, South America buyer for Tayu's UK importer Enotria & Coe, tells db. "And the wine has consistency year on year."