The Navy needs a high/low mix of manned and unmanned platforms

Steven Wills, in this op-ed, argues that the Navy will always need larger ships, and that an “all or nothing” approach relying on unmanned vessels simply won’t work.

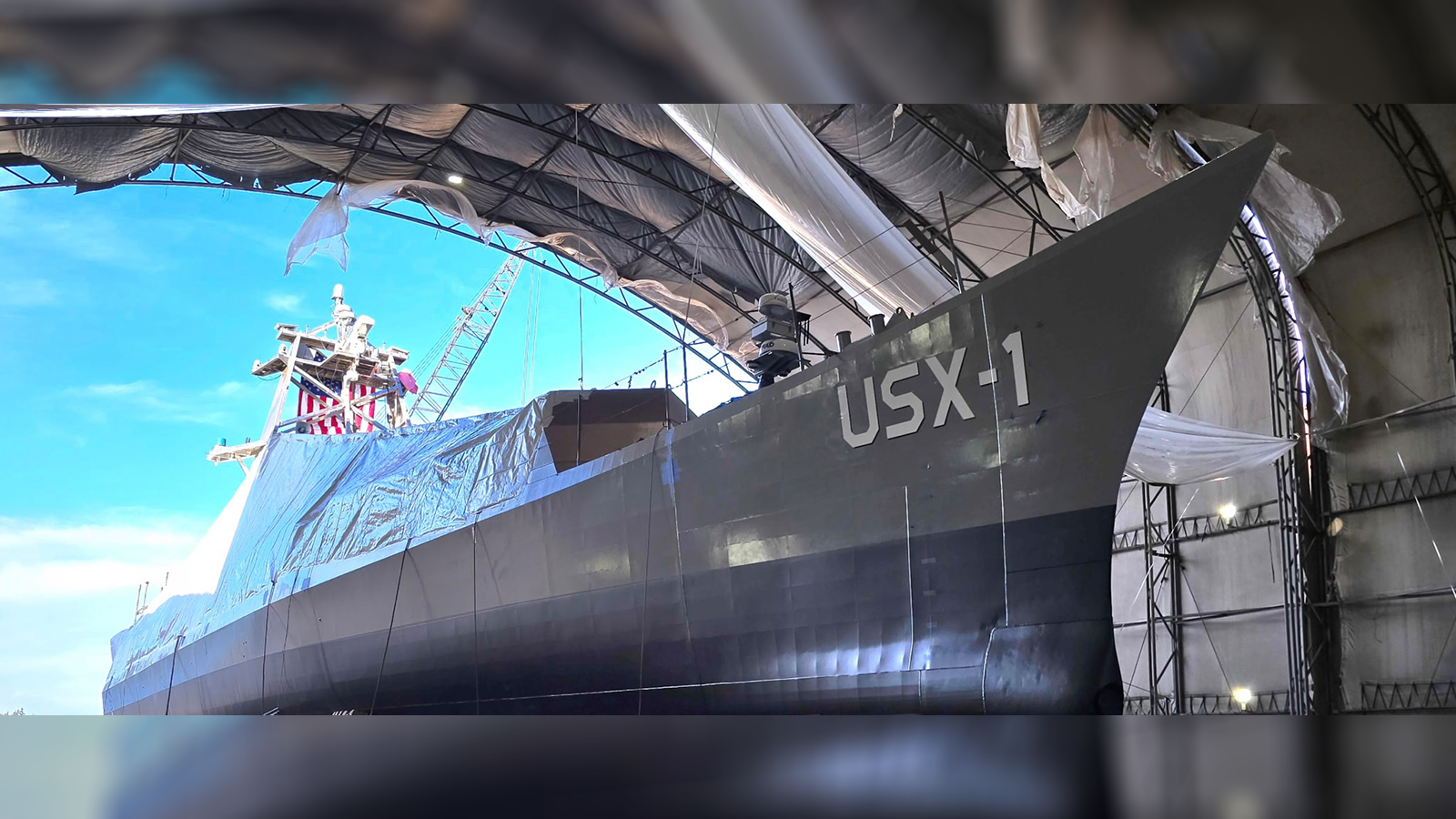

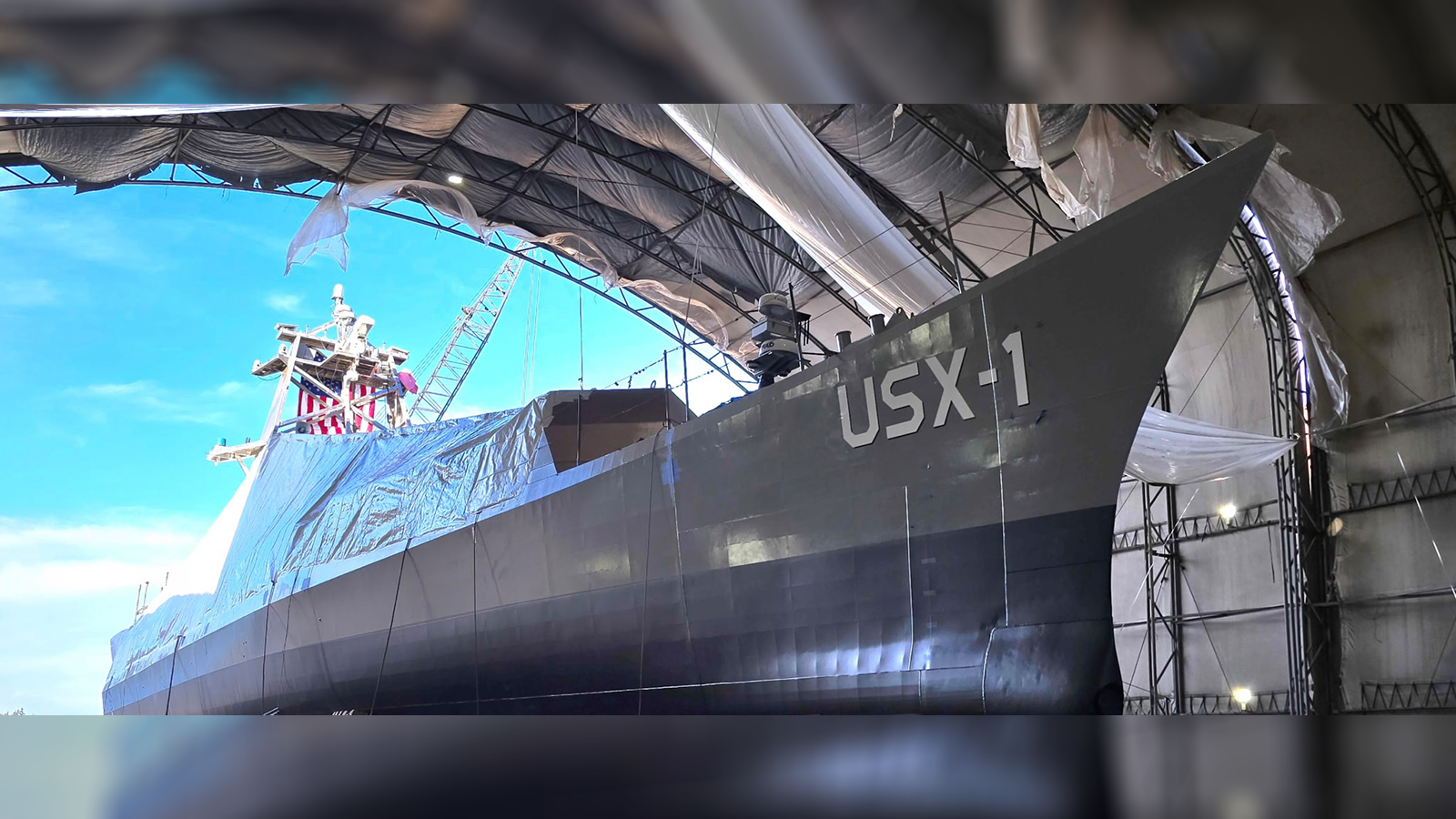

DARPA’s NOMARS is a 180-footlong warship designed from the ground up to not have humans aboard. (Photo courtesy of DARPA)

A recent Breaking Defense opinion piece by retired Army general John Ferrari suggests a massive restructuring of the Navy away from manned aviation, largely by shrinking the numbers of larger surface ships in favor of AI-driven, unmanned small ships like gunboats or patrol craft, and cheap, attritable drone aircraft.

The Navy does have several shipbuilding challenges that need to be corrected, but the replacement of existing ships by small (i.e., cheap) ships, something critics have been saying since the 1982 Falklands war, is not the solution. In truth, this approach is fundamentally at odds with the global battlespace where the Navy operates, often far from land base support.

Combat in Ukraine is often used as the example that suggests mass swarms of small, attritable drones will overcome “legacy” weapons like the tank, the helicopter, and the surface warship. But the applicability of the Ukraine situation to sea, especially with the large oceans that would be in play in a great power battle, is limited. Land battle offers infinite space from which to deploy these small drones, often in short-range combat well within their operating parameters. That’s why naval combat in the Black Sea by Ukraine has been primarily land-based in terms of its launch point.

Naval combat outside the immediate littoral space usually takes place over much longer ranges and/or at a much faster pace, as shown recently in Red Sea missile and drone engagements. Iranian and Houthi drones were forced to travel hundreds of miles at relatively low speeds due to power limitations to reach their potential targets. There was plenty of time for US surveillance assets and systems to locate, target and destroy those drones. Drones, like other weapons such as cruise missiles, are best employed at shorter ranges, and littoral areas where drones work best are already dangerous for surface warships, with cruise missiles and mines being the most significant threats. The Navy will need to better prepare for drone threats in those confined waters, but that’s just another component of what the ghost of Donald Rumsfeld would say is a “known known.”

Focus on the short-range drone conflict in Ukraine also fails to understand the Navy’s operational geography. The Navy must bring all its assets to any fight from remote locations including the continental United States. Gunboats and small platforms, manned or unmanned, take time to cross global ocean spaces to the fight, often arrive in theater not ready for operations due to damage incurred from weather or just crew fatigue and require more frequent servicing with fuel and weapons to remain in the fight.

Unlike ground forces, the Navy must stage operations from the sea and needs larger platforms to carry, support and provide force protection to smaller units. There will always need to be a sizable number of larger and more capable ships to support a sustained fight in the maritime and littoral environments, and if needed later, over the beach and ashore. No mass pivot to smaller warships will support such forward-deployed operations.

These realities are why the Navy has focused on the concept of manned and unmanned teaming, rather than the wholesale replacement of manned systems. While Ferrari acknowledges that, “longer ranges will require larger unmanned systems due to weight and power,” he does not suggest how such systems will be controlled in a contested environment — another major challenge. AI alone is not enough, and the Navy’s current approach of manned and unmanned teaming represents a better method for an expeditionary force without land bases to best operate unmanned systems.

Air teaming of manned and unmanned units is demonstrated in the short film “Sea Strike 2043,” which details the use of unmanned strike and electronic warfare units with the F-35C in a future scenario. The DARPA Defiant unmanned/minimum manned ship, with sixteen vertical launch missile cells, has been suggested for employment as an adjunct magazine, electronic warfare support and possible fuel carrier for surface ships.

Finally, the ORCA large unmanned underwater vehicle is moving toward dangerous missions like minelaying and reconnaissance inside hostile waters. These platforms and larger units can all bring small, numerous unmanned systems and drone weapons to the fight as well. None of the Navy’s unmanned systems have the full potential to support operations in the absence of manned warships, whose mission they ultimately support.

All-or-nothing force structure changes are often ill-informed and fail in global combat. Germany’s World War two decision to drop focus on its surface fleet and naval air arm and exclusively build submarines condemned those submersibles to destruction at the hands of Allied air and surface forces they could not combat. A US Navy shift to a much larger fleet of small, unmanned and drone units would be equally disastrous in the operational and tactical levels of war.

Manned and unmanned teaming represents the best way forward for unmanned weapons employment. It’s not a 180-degree course change, but rather a continuous turn to take advantage of the revolution of the unmanned systems.

Steven Wills, PhD is the navalist at the Center for Maritime Strategy at the Navy League of the United States. He is the editor of Returning from Ebb Tide, Renewing the United States Commercial Maritime Enterprise, published by Marine Corps University Press this year, Strategy Shelved, the Collapse of Cold War Maritime Strategic Planning, published by U.S. Naval Institute Press in 2021, and with former Navy Secretary John Lehman, Where are the Carriers, U.S. National Strategy and the Choices Ahead, published by Foreign Policy Research Institute in 2021.

.jpg)