How to leverage US nukes overseas

The US should use an international desire for nuclear weapons as geopolitical bargaining chips, write two nuclear experts.

An Air Force Global Strike Command unarmed Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missile launches during an operational test at Vandenberg Air Force Base, Calif., Sept. 2, 2020. (U.S. Air Force photo by Vandenberg Air Force Base Public Affairs)

As Beijing accelerates its nuclear buildup and Moscow brandishes its nuclear weapons against NATO, there’s an opportunity to leverage America’s overseas nuclear weapons deployments to check Russian and Chinese nuclear misbehavior.

France is making noise about expanding a nuclear umbrella to other European nations. Poland and South Korea are publicly calling for Washington to deploy US nuclear weapons on their soil and Sweden has announced its willingness to host US nuclear weapons in wartime. Vice President J.D. Vance, meanwhile, has expressed misgivings about such deployments. Even if the US unambiguously committed to the deployments that these allies seek, there is a further complication: The legal and strategic foundations for US nuclear sharing are no longer convincing — if they ever were.

The United States stations more nuclear weapons overseas than any other country. Crucial to this defense posture is the interpretation that the United States places on the word “control” in Articles I and II of the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT). The US and Russia negotiated over the word “control” nearly 60 years ago. A shared understanding of the word that the two then-Superpowers reached made US forward deployments permissible so long as Washington retained “control” over the weapon’s use, as the Soviets wanted to prevent West Germany from ever firing US weapons on its own. The US insists that this understanding is binding today — and that any prohibition on transferring control would disappear if war were to break out.

Initially, this bilateral understanding was secret. By the end of 1968, the year that the NPT was opened for signature, 56 countries had signed the Treaty. Most, however, were unaware of the US-Russian interpretation of what “control” meant under the treaty.

Today, China, Egypt, Indonesia, Mexico, and a broad bloc of developing countries insist that US nuclear sharing violates both the letter and spirit of the treaty. Their skepticism has grown louder at each of the NPT Review Conferences since 1995. The Chinese have recently done extensive analysis taking aim at Washington’s arguments on the binding nature of its 1967 agreement with the USSR, including the US position that, in the event of war, the US is at liberty to transfer control of nuclear weapons to allies.

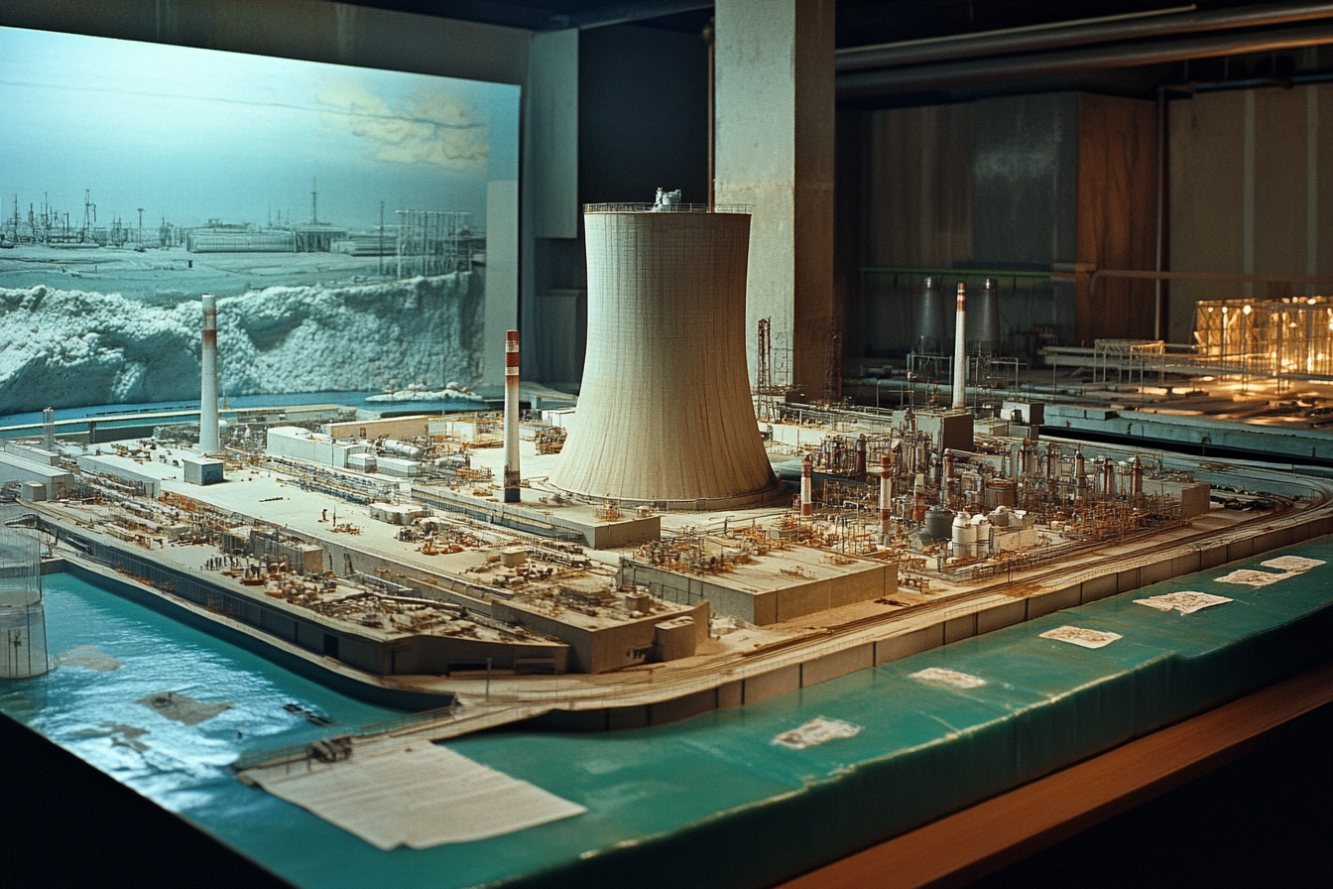

Meanwhile, Russia deployed nuclear weapons to Belarus in 2023 — its first deployment abroad since the Cold War. This coincided with a new Russian doctrine authorizing preemptive nuclear strikes in response to conventional threats. And China’s nuclear stockpile has surged past 600 operational warheads and its expansion is supported by expanding plutonium production, including new fast reactors and reprocessing plants. With its buildup, China aims to deter the US from defending Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, and it comes as China refuses to engage in serious arms control talks.

These nuclear developments have reignited calls from allies in Europe and East Asia for America to deploy its nuclear weapons on their soil. Answering these calls with more deployments, however, would be a mistake.

The United States originally deployed thousands of nuclear weapons overseas because it had no quicker way to get them to the front line. With today’s much-improved methods of delivery — ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and intercontinental range bombers — that rationale no longer holds. Moreover, withdrawing forward-deployed nuclear weapons at the end of the Cold War removed what effectively were target sinks; sending these weapons back now would only reintroduce these vulnerabilities.

Of course, US allies want to be reassured, but rather than give in to their demands and send more US weapons overseas, Washington should use this moment to reframe its nuclear posture and diplomacy.

First, in Europe, the US should condition any removal of US nuclear weapons in NATO on reciprocal Russian steps — specifically, relocating Russia’s theater nuclear forces to verifiable sites east of the Urals. This would shift attention back to Moscow’s aggression and give NATO a principled basis for maintaining the status quo unless real arms control progress is made.

Second, in Asia, Washington should publicly link any future regional deployments to China’s plutonium production and its refusal to enter arms control negotiations. If Beijing verifiably halts its reprocessing activities and engages seriously under Article VI of the NPT, the US could pledge not to station nuclear weapons in the region.

Third, for allies like South Korea and Poland, the US should consider alternatives to forward basing. One model, proposed by RAND and the Asan Institute, would allow South Korea to fund the refurbishment of US warheads held in reserve exclusively for its defense — without deploying them abroad and increasing exercises and preparations for their possible transfer in war. This approach, combined with efforts to restrain Russian and Chinese nuclear advances, could bolster allied confidence without incurring the legal and strategic downsides of basing warheads abroad.

These steps wouldn’t weaken America’s nuclear umbrella — they’d reinforce it. They would also position the US as a more credible steward of the NPT ahead of the 2026 Review Conference.

Vice President Vance is right that sending more nuclear weapons abroad should give us pause. What shouldn’t is leveraging Russia’s and China’s fears of their possible redeployment. That we need to get on with.

Henry Sokolski is executive director of the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center in Arlington, Virginia, served as Deputy for Nonproliferation Policy at the Pentagon (1989-93), and is author of China, Russia and the Coming Cool War (2024).

Thomas D. Grant is a senior fellow at the Lauterpacht Centre for International Law at Cambridge, served as Senior Advisor for Strategic Planning in the Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation at the US State Department under the Trump administration (2019–21), and is author of Nuclear Arms Control in Peril (2025) and Aggression Against Ukraine (2015).