How Significant Will The European Emissions Rollback Actually Be?

Europe is relaxing CO2 emission targets after receiving feedback from automakers. The industry is concerned that the present regulatory conditions are going to cost them a fortune, so the European Commission is throwing them a bone by delaying some of the financial penalties. But whether or not this will actually yield positive results for consumers is debatable.

Europe is relaxing CO2 emission targets after receiving feedback from automakers. The industry is concerned that the present regulatory conditions are going to cost them a fortune, so the European Commission is throwing them a bone by delaying some of the financial penalties. But whether or not this will actually yield positive results for consumers is debatable.

Volkswagen expressed concerns that it would need to spend €1.5 billion in fines for failing to meet the limits for 2025. But that's not for a lack of trying. Keep in mind that VW was likewise among the first mainstream brands to try and pivot toward electrification after the Dieselgate issue in 2015. But Renault and Stellantis have confronted similar hardships, with the latter now backpedaling away from electrification plans due to lower-than-anticipated sales.

Reports allege that most of the large automakers have been petitioning European leadership for months to soften standards a bit. Those pleas have not fallen upon deaf ears, especially now that there’s been a visible decline in new vehicle sales.

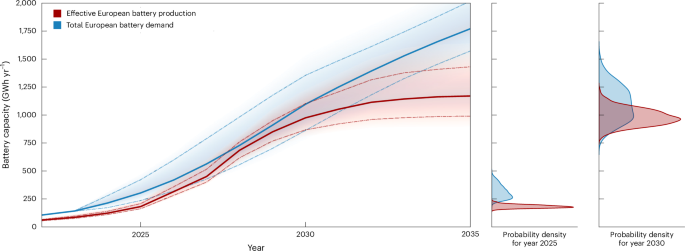

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen issued an announcement earlier this month that manufacturers would receive a two-year extension for meeting the planned tighter CO2 emissions rules for 2025. But the region is still targeting mandatory electrification and will be advancing tighter emission limits in 2025, 2030 and 2035. From there, all new automobiles will have a legal obligation to be considered “zero emissions.”

The only relevant change is that Europe will now average automakers’ regulatory performance between 2025 and 2027. Companies that underperform in one year will be allowed to make up for it in another before incurring any fines. Everything else will remain the same.

Fleet-wide average CO2 emissions are still supposed to decline by 15 percent between 2025 and 2029. Then, they’ll be required to decline by another 50 percent from 2030-2035 before the formal combustion bans take effect.

“We will stick to our agreed emissions targets but with a pragmatic and flexible approach,” Von der Leyen said.

The flexible approach isn’t really a softening of emissions regulations so much as it is delaying targets for European automakers. Sales are down within the region, including EV sales. This has been attributed to a combination of fresh competition from China, a lackluster economy, elevated production costs, and consumers not pivoting toward all-electric models as quickly as anticipated. However, the European Commission seems largely blind to the fact that increased regulations have effectively resulted in manufacturers boasting new-vehicle lineups that are prohibitively expensive and ultimately less appealing to consumers.

Whether we’re discussing Europe or North America, the problem is largely the same. But often so is the solution. The government establishes tightening regulatory targets with the end result being ubiquitous electrification (often supported by automakers because of subsidies) that have resulted in costly automobiles with questionable reliability, lackluster serviceability, and features nobody really seems to want. Sales predictably decline because consumers are either disinterested or simply cannot afford the resulting products and the government suggests everyone just wait a couple of years, assuming buyers will eventually change their minds.

It’s not a serious compromise and it’s difficult to imagine it actually doing much to improve sales within the region. In fact, while the European Commission gently stalls the timeline for manufacturer emission quotas, it wants to issue new rules to force more commercial work vehicles (which make up a majority of the European market) to become EVs.

“Europe’s emission standards for new cars and vans provide long-term certainty for investors. So they remain,” Apostolos Tzitzikostas, the European Commissioner for “Sustainable Transport and Tourism,” told the media. “But we must also be pragmatic.”

The trading bloc has also said it wants to spend €1.8 billion over the next two years in the hopes of improving the supply chains necessary for the production of EV batteries. But this could very easily advantage China, as it remains the battery production capital of the world, and is poised to continue pushing companies toward electrification by creating more financial incentives for the industry.

That said, some analysts are claiming that the planned changes could save European automakers up to €3 billion. This is assumed to stem from a combination of being able to field models that will sell a little better and avoiding having to pay emission fines to the government.

Reception of the plan has been predictably mixed. The European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) has endorsed the measures taken. But it still said a few things were missing — namely increased government incentives for EV, assistance in helping to lower production costs, and more money for charging infrastructure.

“The proposed flexibility to meet CO2 targets in the coming years is a welcome first step towards a more pragmatic approach to decarbonisation dictated by market and geopolitical realities,” said Sigrid de Vries, Director General of ACEA. “It holds the promise of some breathing space for car and van makers, provided the much-needed demand and charging infrastructure measures now also actually kick-in.”

Groups prioritizing electrification have called it a slap in the face, however. We’ve even seen some limited protesting from environmental activists. This is despite the changes not really doing much more than briefly stalling some of the financial penalties incurred by automakers. The European Union is still on track to effectively ban internal combustion engines within the next decade.

Automakers with above-average EV sales were likewise less enthusiastic than those struggling to sell them. Geely-owned Volvo has suggested that other automakers had sufficient time to make the necessary changes. It and other EV-focused brands (e.g. Tesla) now run the risk of losing money they expected to make by selling carbon credits to rivals that were deemed out of compliance.

Regardless of how you feel about the regulations, there is a staggering amount of money tied up in everything at this point. Consumers are sick of overpriced vehicles with features they don’t want, impacting sales. The government is worried about balancing fines with subsidies designed to promote electrification. Automakers are bickering about whether or not they’ll be able to avoid fines or sell off their carbon credits, depending on whether or not they could sell the right type of vehicles from a regulatory standpoint. But they’ve also spent billions in order to build EVs that aren’t selling as quickly as hoped.

With so much political hysteria and money involved, It’s almost impossible to imagine a realistic scenario that would please all the parties involved and even fewer that would directly benefit the typical European car buyer. That particular demographic presently seems to be the very last priority for both automakers and regulators.

[Image: Volkswagen Group]

Become a TTAC insider. Get the latest news, features, TTAC takes, and everything else that gets to the truth about cars first by subscribing to our newsletter.

.jpg)