As space becomes more crowded, Space Force turns to AI

The newest service wants to understand where automation can augment—or even replace—humans in monitoring space for threats.

Long gone are the days when a single airman observed one satellite or space object to make sure it wasn’t acting strangely or veering toward possible collision, Seth Whitworth said. Now, one of the big questions for the Space Force is how many space objects can a single guardian fly, monitor, or track at once, with the possible help of automated tools.

“What trust level is required where I now can have one guardian reviewing 10, 20, 1,000? I don't know what that number is. It's the conversations that we're having,” he said.

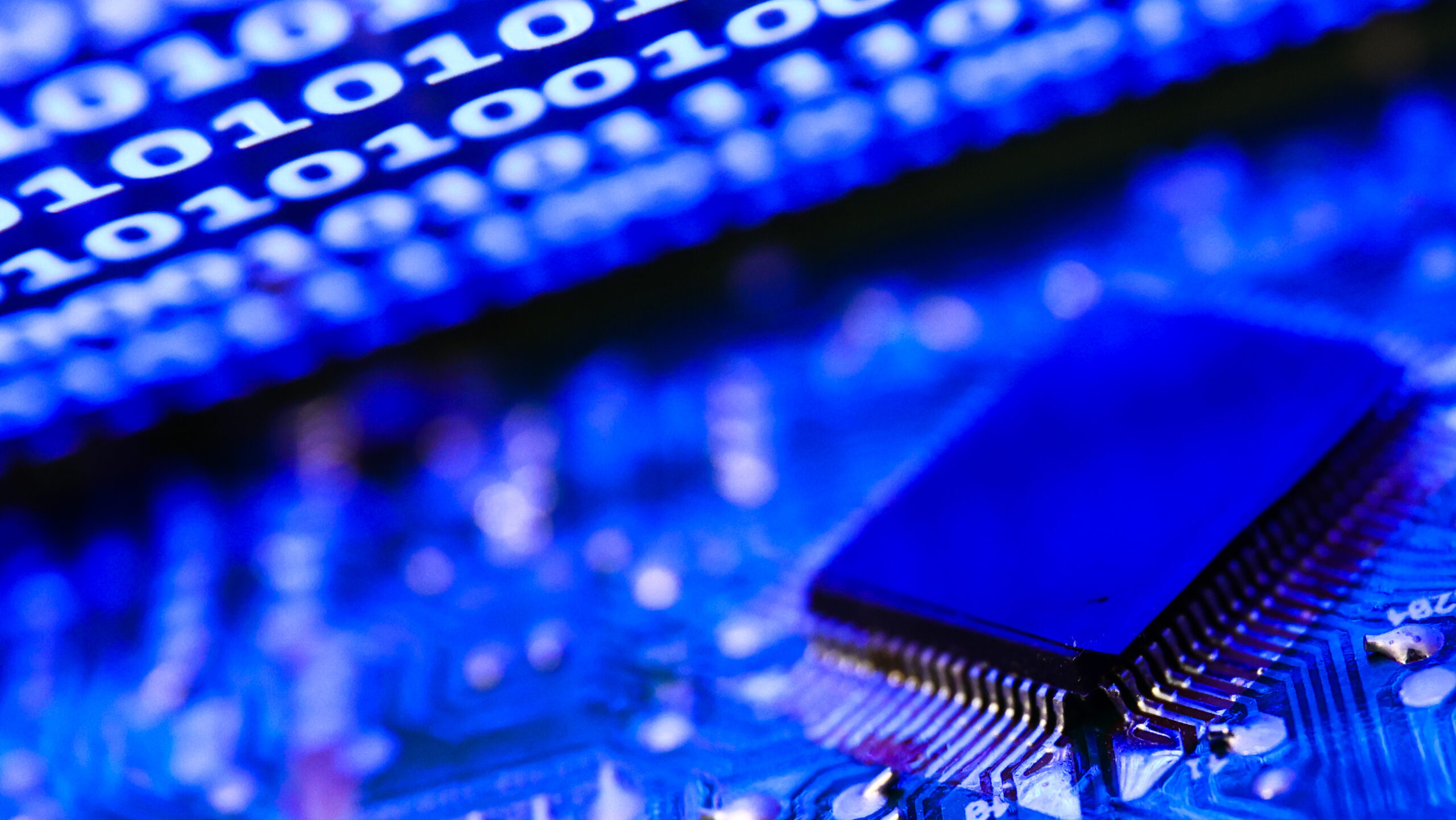

Guardians are now training automated tools on their activities and processes, in order to understand and build trust for the tools and find safe applications for AI, he said, such as helping to draft performance reports or participating in wargames. But establishing that trust will need to be a rigorous, ongoing process.

“If you go out and talk to guardians, I think they would say that they want a chat-like capability,” Whitworth said.

Nate Hamet, the founder and CEO of Quindar, a Colorado start-up that builds AI tools for monitoring space missions, said the company has already created a type of chatbot for space operators, based on “the conversations that we see our users” having. Those conversations include questions about the rules for particular maneuvers, propulsion systems for different objects in view, and more.

But the sheer volume of space objects—and thenew data about those objects—means the Space Force must also consider ways to deploy AI for other missions, like tracking or flying satellites.

“We have to evaluate the risk of, where can we pull guardians out? Where is that trust level,” necessary to hand that role over to an automated agent, said Whitworth.

Pat Biltgen, a principal at Booz Allen Hamilton focused on artificial intelligence, said that as the human task of monitoring the space domain and responding to possible attacks becomes more challenging, the military must consider allowing automated agents to do much more. Relying on a so-called “human-on-the-loop” to monitor automated systems may speak to present-day concerns about human control, but as AI entities become more effective, interconnected and safe, highly-distracted human monitors could actually detract from safety, he said.

He described a hypothetical “worst nightmare” scenario in which reliance on human judgement becomes a liability, as a tired, isolated human operator is presented with too much data to make the best decision, but still retains authority to do so.

“There's this massive, multi-billion dollar system …It's all designed to work together in network-centric warfare. And there's one person on Christmas Eve that is the lowest-ranked person, stuck with the least amount of leave, that has a big red button that says, ‘Turn off the United States.’” ]]>