A 3D-printed submarine? Not likely, but maybe something close

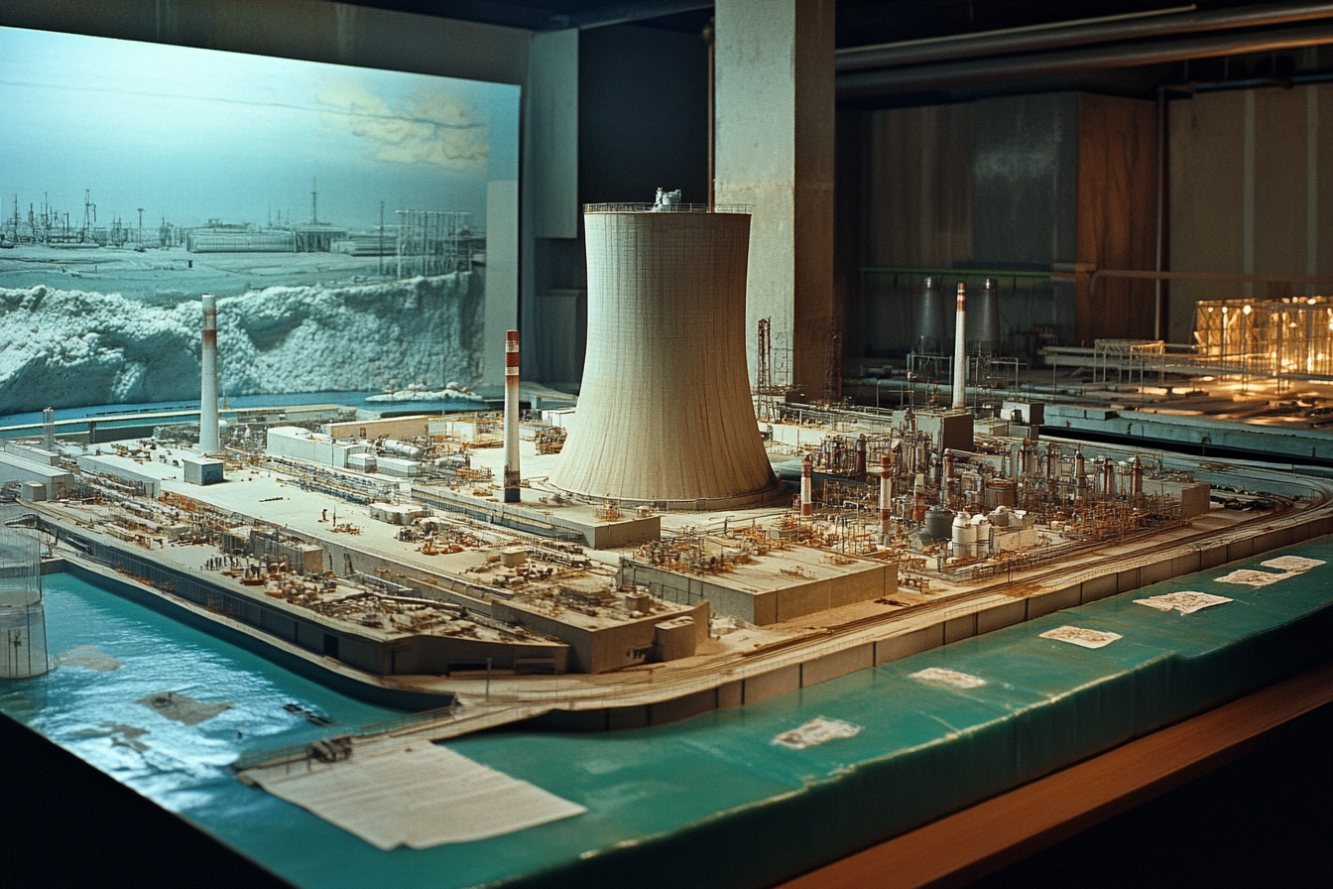

The Navy is bumping up its use of additive manufacturing to make critical, delay-prone submarine parts, said Christopher Miller, NAVSEA’s executive director.

“I could go anywhere in the Navy, and you will see additive manufacturing, but it's not solving our biggest problems," Christopher Miller, the executive director of Naval Sea Systems Command, said during Govini's Defense and Data Summit in Washington, D.C., on Wednesday.

But in the last year, the Navy—especially its Maritime Industrial Base Program office—have been upping their efforts.

"We have really pressed the accelerator in going after the really hard problems. Not the simple polymer things, but really hard material combinations that really do provide parts into our availabilities,” Miller said.

For example, one boat is using additive manufacturing for more than 100 critical parts. But it’s taken time to get the supply chain and technical communities comfortable and skilled with the technology.

"We are starting to see a return on additive manufacturing," Miller said. "We've spent, in the last couple years, over $200 million just in added manufacturing areas to try to accelerate this area...but we still have a lot of work to do."

He said it’s unlikely that any U.S. sub will ever be fully 3D-printed.

"I'm not sure it'll ever be 100 percent but clearly we can do better than we're doing today," Miller said. "We can build bigger components...the challenge is some of these things get to be very, very large, and so you still have to be able to bring these together, integrate them, stack them on top of one another. But we have been having some really good conversations about how far [we can] really press those materials to build bigger and bigger, because we all recognize there's great opportunity there."

Additive manufacturing is also key to the trilateral AUKUS agreement. Earlier this year, Australian tech manufacturing company AML3D announced delivery of prototype tailpiece components made of copper-nickel for the Virginia-class nuclear submarine. Production took five weeks, a fraction of the 17-month average, according to the news release.

Efforts to boost production

As the Navy has been struggled with a years-long backlog in submarine production, officials have suggested that 3D-printing might be the only way to get parts fast enough. But that hasn’t stopped the service from trying a lot of other things as well.

From 2014 to 2023, the Pentagon poured nearly $6 billion into the shipbuilding industrial base in a bid to get more ships faster, according to a Government Accountability Office report released Feb. 27. That number, which includes contract incentives and direct investments, is expected to double to $12.6 billion through fiscal year 2028.

The investment is an attempt to correct decades-long slowdown in naval shipbuilding capacity and an atrophied workforce that goes with it. But it's unclear whether those investments will have a lasting impact.

"The Department of Defense (DOD)—specifically the Navy and Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD)—spent billions to support the shipbuilding industrial base. This included funding for infrastructure and workforce improvements for shipbuilders and their suppliers. But it has yet to fully determine the effectiveness of that support (i.e., its return on investment), though it has taken steps to do so," GAO wrote in its report.

The Pentagon and Navy have awarded contracts to look into supply-chain needs and evaluate how investments are spent. But those efforts, broadly, have not been coordinated "to prevent duplication or overlap in spending. For example, the Navy and OSD do not coordinate across all investment efforts—such as between submarines and surface ships—though they both make related investments in workforce and infrastructure for these ship categories," GAO wrote.

Moreover, the Navy hasn't created performance metrics to measure investments' effectiveness.

"Without better visibility across investments and established performance metrics, the Navy and OSD cannot ensure their investments in the shipbuilding industrial base are an effective use of federal funds to help build a larger fleet," the report states.

On the workforce side, one of those investments is the Navy-backed ad campaign—”We Build Giants”—often seen at sporting events which promotes the job-hunting site Buildsubmarines.com.

Miller said the ad campaign seems to be going well, but the jury is still out on turning clicks into careers.

"It's working in terms of getting people interested," he said. "I just want them in the workforce," whether that's for the Navy or at a public or private shipyard.

Then he said: "What I'm really monitoring right now is our ability to retain...we have to show commitment to that workforce, keep them actually excited about the work, get them in the game, and get them to stay in the game."

Workforce constraints are a frequent point of contention as the Navy pushes to make more submarines in preparation for a potential conflict with China in the Indo-Pacific region---an issue is likely to be a major focus of the Trump administration.

"There's a lot of turnover---higher than what you would normally see in attrition. And so that's what I think is our next big challenge. I think that we're getting there in terms of recruiting, we're partnering with the regional community college and then tech, tech schools. The next big thing is we got to talk about all the other stuff that keeps people into the job," from creature comforts like HII's Chik-Fil-A in the shipyard to quality of life needs such as childcare and housing.

"This generation coming into the workforce has a desire to serve...but they also have a very short tolerance until they really want to start seeing where they're making a difference. And so we've got to do more," Miller said.

"We've put over $500 million in workforce development, but we’ve got to work closely with the states and the regions to make sure we're addressing these things. A lot of these issues are regional...but we’ve got to attack it everywhere we can so those people actually stay on the job."

Brent Sadler, senior research fellow at the Heritage Foundation said the turnover rate for commercial and naval shipyards can be as fast as six months--which is a problem for highly technical jobs.

"The only way you're going to get through that is you have to push through it and just keep [up] those demands for contracts for work. And eventually that 10 percent that decide to stay for 20 years will compound and you'll actually have a much more robust, much more capable," workforce, Sadler said during the Govini panel on shipbuilding and manufacturing.

But the regional challenge is a bit trickier because there have to be considerations about where shipyards are built near a population that would want the jobs.

"Are we building ships where people want to build ships? Not the customer or the industry, but the workforce," Sadler said. "Moving to the southeast makes sense...but also from strategic perspectives, the lakes, Great Lakes, but also looking over to the West Coast. Because if we do get into a war with China, we're going to need to have places on the west coast to do the repairs. And so if you have yards big enough to build a Virginia-class submarine, build a four class aircraft carrier. In that region, the country, you can also repair them if they get hit and they have to be repaired quickly to get back into the fight with China. So there's a geographic piece to this that also is informed by a labor demographic." ]]>