Who Decides? Rethinking the Corporate Franchise from a Stakeholder Perspective

There’s an old political aphorism that if you’re young and conservative, you have no heart, and you’re old and liberal, you have no head. Idealism, in other words, crumbles over time into realism. Youth imagines humanity’s potential and ideals, while older folks have seen people acting at their worst. For at least a century, corporate […]

Grant M. Hayden is the Richard R. Lee Jr. Endowed Professor of Law at Dedman School of Law, and Matthew T. Bodie is the Robins Kaplan Professor at University of Minnesota Law School. This post is based on their article forthcoming in the Minnesota Law Review.

There’s an old political aphorism that if you’re young and conservative, you have no heart, and you’re old and liberal, you have no head. Idealism, in other words, crumbles over time into realism. Youth imagines humanity’s potential and ideals, while older folks have seen people acting at their worst.

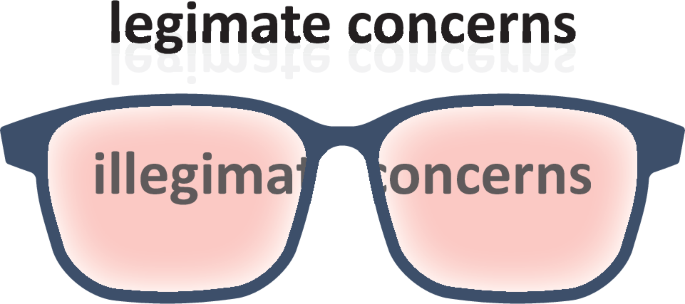

For at least a century, corporate governance has wrestled between the theories of shareholder primacy and stakeholderism. Shareholder wealth maximization presents a mendacious view of human nature focused on self-interest and greed, but it theoretically channels these traits to power the engines of commerce and maximize societal efficiency. Stakeholderism, on the other hand, endeavors to meet the needs of all, envisioning corporate board members as Platonic guardians or mediating hierarchs who can wisely balance competing interests and sidestep crippling internal conflict. With its narrow focus on individual self-interest, shareholder primacy has no heart—it seeks to make shareholders as rich as possible, with hopefully positive secondary effects. Stakeholderism has no head—it fuzzily bestows its corporate leaders with heroic attributes and hopes everything will work out.

In A Democratic Participation Model for Corporate Governance, we introduce a bit more realpolitik to stakeholderism. Instead of hoping for the best or acceding to the worst, we argue that corporate law should change the structure of corporate governance to better balance power between participants. Taking stakeholders seriously means giving them voting rights. The longstanding puzzle remains, however: how? The shareholder franchise appears easy to administer and weigh, with each share assigned voting power at the moment of its creation. In comparison, what stakeholders should get the right to vote, and how much voting power should they have relative to each other? (more…)