When I quit road testing, I want to be a driving instructor

Road testers' habits die hard, even driving a pick-up truck in a quarry This may well say more about my own lack of reflection on the subject than anything else, but the job of a road tester seems to me to be quite particular and the skills that it requires a little, shall we say, non-transferable. I’ve always imagined that I personally would be ill-matched to the corporate culture of life as a modern automotive development engineer, quite aside from being woefully unqualified for the technical requirements. I wouldn’t make it out of my first week I’m not talented or fit enough for a career in motorsport. Not diplomatic or patient enough to work in modern corporate communications either. Even among other media people, us car testing types are frequently accused of living life on Road Test Island (Iran’s petrol prices, the Isle of Man’s speed limits, a Kwik Fit on every corner, no internet and a legally enforceable limit on magazine publishing frequency of once a quarter). The one other line of work that I might consider, it seems to me, is instruction. Not driving instruction of proper learner drivers reversing around corners and doing three-point turns, I hasten to add: advanced road or track driving tuition of the kind that a working life misspent driving a disproportionately powerful selection of cars on and in a diverse mix of circuits and environments might at least partly prepare one for. Honestly, if only for a moment or two, I’ve thought about it (we all have bad days, after all). The most recent occasion was on the UK press launch of a pick-up truck that involved some off-roading in a purpose-built demonstration venue. I was paired with a lovely chap who’d had his own rally team and was therefore well used to challenges far more serious than the muddy tracks we were dealing with. So his first trick was in effortlessly and instantly putting me at ease before we’d even turned a wheel. As we went around, we simply talked cars. And planes, and engines, and electric motors – and, very occasionally, he told me to stop and select low range, hold onto a gear, avoid a rut, use more power (or indeed less) or wiggle the steering wheel a bit to help dig us out of a hole. There was an art to what he did, because never did I feel like I was being lectured or dictated to, that I’d erred or offended or displayed any inability to follow simple instructions (which, at some point, I no doubt did). This gent just allowed me to concentrate on and enjoy what I was doing, didn’t put himself in the way and gave me the odd gentle prompt when I needed it. Something similar happened on the press launch of the Land Rover Defender Octa earlier this year. Land Rover has a lot of practice when it comes to running demonstration drives suited to showing off the capabilities of its vehicles, and this one took in rock-crawling, rally stage-like handling testing and sand-duning. I wasn’t quite a novice at any of it but, as I habitually do, I went at it with nothing to prove, curious about what I could learn and treating the fellow next to me like a fellow human being whom I wouldn’t want to make uncomfortable in any case. Apparently my sand driving in particular showed at least some natural aptitude – which is just another way of saying that an expert instructor finds a way to make you feel good about what you’re doing. Could I do it? Perhaps – but I reckon I’d prefer off-road enthusiasts to millionaire customer prospects and sand dunes to circuits. And I’m in no hurry to give up this lark just yet.

Road testers' habits die hard, even driving a pick-up truck in a quarry

Road testers' habits die hard, even driving a pick-up truck in a quarry

This may well say more about my own lack of reflection on the subject than anything else, but the job of a road tester seems to me to be quite particular and the skills that it requires a little, shall we say, non-transferable.

I’ve always imagined that I personally would be ill-matched to the corporate culture of life as a modern automotive development engineer, quite aside from being woefully unqualified for the technical requirements. I wouldn’t make it out of my first week

I’m not talented or fit enough for a career in motorsport. Not diplomatic or patient enough to work in modern corporate communications either.

Even among other media people, us car testing types are frequently accused of living life on Road Test Island (Iran’s petrol prices, the Isle of Man’s speed limits, a Kwik Fit on every corner, no internet and a legally enforceable limit on magazine publishing frequency of once a quarter).

The one other line of work that I might consider, it seems to me, is instruction. Not driving instruction of proper learner drivers reversing around corners and doing three-point turns, I hasten to add: advanced road or track driving tuition of the kind that a working life misspent driving a disproportionately powerful selection of cars on and in a diverse mix of circuits and environments might at least partly prepare one for.

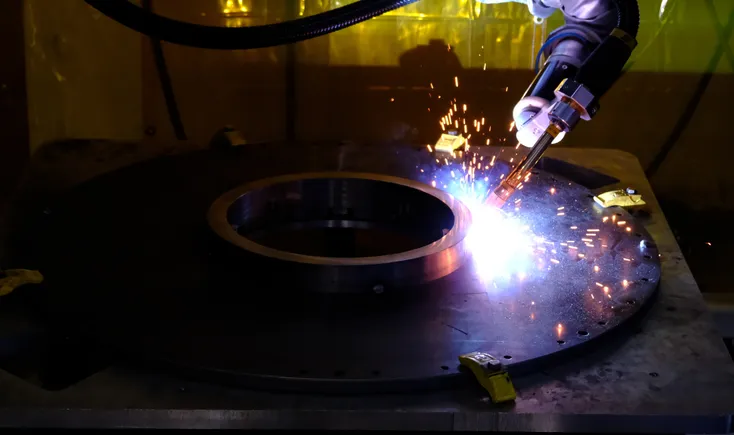

Honestly, if only for a moment or two, I’ve thought about it (we all have bad days, after all). The most recent occasion was on the UK press launch of a pick-up truck that involved some off-roading in a purpose-built demonstration venue.

I was paired with a lovely chap who’d had his own rally team and was therefore well used to challenges far more serious than the muddy tracks we were dealing with. So his first trick was in effortlessly and instantly putting me at ease before we’d even turned a wheel.

As we went around, we simply talked cars. And planes, and engines, and electric motors – and, very occasionally, he told me to stop and select low range, hold onto a gear, avoid a rut, use more power (or indeed less) or wiggle the steering wheel a bit to help dig us out of a hole.

There was an art to what he did, because never did I feel like I was being lectured or dictated to, that I’d erred or offended or displayed any inability to follow simple instructions (which, at some point, I no doubt did).

This gent just allowed me to concentrate on and enjoy what I was doing, didn’t put himself in the way and gave me the odd gentle prompt when I needed it.

Something similar happened on the press launch of the Land Rover Defender Octa earlier this year. Land Rover has a lot of practice when it comes to running demonstration drives suited to showing off the capabilities of its vehicles, and this one took in rock-crawling, rally stage-like handling testing and sand-duning.

I wasn’t quite a novice at any of it but, as I habitually do, I went at it with nothing to prove, curious about what I could learn and treating the fellow next to me like a fellow human being whom I wouldn’t want to make uncomfortable in any case.

Apparently my sand driving in particular showed at least some natural aptitude – which is just another way of saying that an expert instructor finds a way to make you feel good about what you’re doing.

Could I do it? Perhaps – but I reckon I’d prefer off-road enthusiasts to millionaire customer prospects and sand dunes to circuits. And I’m in no hurry to give up this lark just yet.

![What you need to know before you go to Sea Air Space 2025 [VIDEO]](https://breakingdefense.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2024/05/Screen-Shot-2024-05-14-at-12.19.19-PM.png?#)

.jpg)