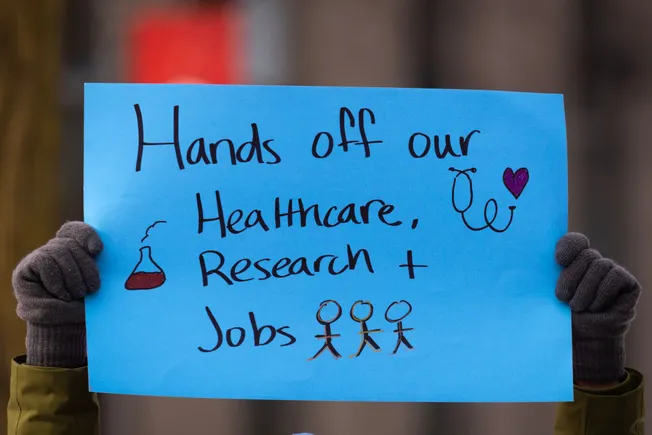

The Shared DNA of Roe and Dobbs: Potential Life as a Tool of Subordination

For the Balkinization Symposium on Legal Pathways Beyond Dobbs. Kimberly Mutcherson [1] In Roe v. Wade and Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health, Justices Blackmun and Alito claim they are not choosing a theory of life and/or declaring when life begins nor are they declaring a fetus to be a constitutional person. While the two opinions come to very different conclusions about the existence of a right to an abortion in the federal constitution, they share the common thread of failing to take serious account of the rights of the pregnant woman — a person whose life and personhood are not in question. Thus, rather than avoiding declaring a theory of life, the Court has consistently articulated a theory of pregnant life by refusing to accord pregnant women rights of autonomy and bodily integrity given to any other competent adult person in the vast majority of circumstances. In Dobbs, Alito essentially erases pregnant women altogether in favor of protecting the right to life of a fetus, presumably at any point during a pregnancy. In Roe, Justice Blackmun’s majority opinion created a structure that assumed that the desires of a person living an actual life could be forced to yield to “potential life”[2] at least during the 3rd trimester of pregnancy when a fetus is presumably “viable.”[3] Given the deep commitment to protecting bodily integrity that permeates U.S. law, those who subordinate pregnant women to the nascent lives they carry bear the burden of articulating a secular account of potential life as paramount to lives in being, and the Court’s abortion jurisprudence consistently failed to do so. The theory of pregnant life that emanates from abortion cases remains the centerpiece of the jurisprudence of pregnancy. As such, it subordinate pregnant women by holding that what is owed to potential life, even before viability is, or at least can be, greater than what a parent owes to a child who exists in the world. To the extent that abortion jurisprudence reflects a theory of parenthood in which a woman becomes a mother from the moment she becomes pregnant, then it would seem logical that the same theories of obligation to children should apply between parents and their living children as between pregnant women and the future children they gestate. Yet these obligations are not coextensive. Thus, a central conundrum is how the state interest in potential life can be so compelling, potentially from the moment of fertilization, that a state can force a person to submit to the months long risks and rigors of pregnancy, but the state interest in life post-birth is too shallow to force anyone, including a parent, to submit to bodily intrusions to save their child.One way to illustrate the conceptual problem discussed here is to consider hypotheticals related to pregnancy and risk to a fetus, including the risk of demise, versus a parent faced with decisions about the life of a child already in existence in the world. Imagine that a state orders a pregnant woman with severe anorexia nervosa (AN) to increase her calorie count, perhaps through forced feeding, and limit rigorous exercise to lessen the risk of miscarriage and the demise of her fetus. Presumably, under an Alito formulation of potential life, the state could take this step even before legal viability because waiting potentially increases the risk of pregnancy loss. Now imagine if a woman refused bedrest ordered by a physician. Justice Alito’s theory of pregnant life would allow the state to order her to comply with her physician’s dictates to protect potential life. Perhaps, for the near term, the state’s power would not extend to monitoring a pregnant person’s diet or an order enforcing bed rest, but existing jurisprudence could certainly be used to justify these orders. For instance, there are already accounts of criminal court judges remanding pregnant women into custody to “protect” their fetuses and cases of court-ordered or coercive obstetrical interventions, though typically closer to when a pregnancy is almost at term. The steps states are taking to further entrench their anti-abortion stances only increase the possibility of draconian orders directed toward pregnant women becoming more ubiquitous. In contrast to the pregnant women described above, imagine a parent whose very sick toddler needs a liver transplant. The parent is the only person who is capable of providing a portion of her liver to save her child’s life, but she refuses. One would be hard-pressed to find a family court judge that would order the parent to consent to the bodily invasion of surgery for the benefit of her child. Even if the child needed a stem cell transplant that requires the donor to submit to a less invasive procedure than surgery, a court would not order the parent to subject herself to this procedure in order to save her child’s life. None of this is to say that there could not or would not be moral and ethical pressures brought to bear on this parent, but those press

For the Balkinization Symposium on Legal Pathways Beyond Dobbs.

Kimberly Mutcherson [1]

In Roe v. Wade and Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health, Justices Blackmun and Alito claim they are not choosing a theory of life and/or declaring when life begins nor are they declaring a fetus to be a constitutional person. While the two opinions come to very different conclusions about the existence of a right to an abortion in the federal constitution, they share the common thread of failing to take serious account of the rights of the pregnant woman — a person whose life and personhood are not in question. Thus, rather than avoiding declaring a theory of life, the Court has consistently articulated a theory of pregnant life by refusing to accord pregnant women rights of autonomy and bodily integrity given to any other competent adult person in the vast majority of circumstances. In Dobbs, Alito essentially erases pregnant women altogether in favor of protecting the right to life of a fetus, presumably at any point during a pregnancy. In Roe, Justice Blackmun’s majority opinion created a structure that assumed that the desires of a person living an actual life could be forced to yield to “potential life”[2] at least during the 3rd trimester of pregnancy when a fetus is presumably “viable.”[3] Given the deep commitment to protecting bodily integrity that permeates U.S. law, those who subordinate pregnant women to the nascent lives they carry bear the burden of articulating a secular account of potential life as paramount to lives in being, and the Court’s abortion jurisprudence consistently failed to do so.

The theory of pregnant life that emanates from abortion cases remains the centerpiece of the jurisprudence of pregnancy. As such, it subordinate pregnant women by holding that what is owed to potential life, even before viability is, or at least can be, greater than what a parent owes to a child who exists in the world. To the extent that abortion jurisprudence reflects a theory of parenthood in which a woman becomes a mother from the moment she becomes pregnant, then it would seem logical that the same theories of obligation to children should apply between parents and their living children as between pregnant women and the future children they gestate. Yet these obligations are not coextensive. Thus, a central conundrum is how the state interest in potential life can be so compelling, potentially from the moment of fertilization, that a state can force a person to submit to the months long risks and rigors of pregnancy, but the state interest in life post-birth is too shallow to force anyone, including a parent, to submit to bodily intrusions to save their child.

One way to illustrate the conceptual problem discussed here is to consider hypotheticals related to pregnancy and risk to a fetus, including the risk of demise, versus a parent faced with decisions about the life of a child already in existence in the world. Imagine that a state orders a pregnant woman with severe anorexia nervosa (AN) to increase her calorie count, perhaps through forced feeding, and limit rigorous exercise to lessen the risk of miscarriage and the demise of her fetus. Presumably, under an Alito formulation of potential life, the state could take this step even before legal viability because waiting potentially increases the risk of pregnancy loss. Now imagine if a woman refused bedrest ordered by a physician. Justice Alito’s theory of pregnant life would allow the state to order her to comply with her physician’s dictates to protect potential life. Perhaps, for the near term, the state’s power would not extend to monitoring a pregnant person’s diet or an order enforcing bed rest, but existing jurisprudence could certainly be used to justify these orders. For instance, there are already accounts of criminal court judges remanding pregnant women into custody to “protect” their fetuses and cases of court-ordered or coercive obstetrical interventions, though typically closer to when a pregnancy is almost at term. The steps states are taking to further entrench their anti-abortion stances only increase the possibility of draconian orders directed toward pregnant women becoming more ubiquitous.

In contrast to the pregnant women described above, imagine a parent whose very sick toddler needs a liver transplant. The parent is the only person who is capable of providing a portion of her liver to save her child’s life, but she refuses. One would be hard-pressed to find a family court judge that would order the parent to consent to the bodily invasion of surgery for the benefit of her child. Even if the child needed a stem cell transplant that requires the donor to submit to a less invasive procedure than surgery, a court would not order the parent to subject herself to this procedure in order to save her child’s life. None of this is to say that there could not or would not be moral and ethical pressures brought to bear on this parent, but those pressures would not come from a court order to donate.

An argument likely to be made by those drawing a distinction between the pregnant women and the parents in the above hypotheticals is that when a pregnant woman chooses abortion, she is engaging in an affirmative act to end the pregnancy whereas abortion restrictions and parents who decline to subject themselves to physical interventions to save their children are simply maintaining the status quo. To this I say that being pregnant is not to exist in a state of rest or inaction. A pregnant woman’s body is at work 24/7. Pregnancy is dynamic and physically demanding experience. For most women, pregnancy can bring many pleasures, but it also brings burdens in the form of prenatal visits, invasive testing, changes to eating patterns, interference with work and pleasure, physical and psychic scars, discomforts, permanent changes to one’s body, pains, and new and sometimes unsettling or even permanently life-altering experiences. To bear this experience willingly is far different than being forced to remain pregnant against one’s will.

It is difficult to articulate a plausible reason why a state’s interest in a potential life would be more potent than a state interest in actual life. Yet our current legal regime rests on the idea that the state has more power to override autonomy for potential life than it does for a life in being. This state of affairs has a dizzying array of implications beyond an amorphous concept of privacy and missing from the majority opinions in the abortion cases is limiting language that countenances against the state demanding that parents, caretakers, friends, neighbors or regular citizens make their bodies or body parts available to save the lives of others in a way that is remotely comparable to what restrictive abortion laws require of pregnant women. The answer to this dilemma is not to create more burdens on parents and caregivers, but to re-evaluate what it means to have a constitutional right to bodily integrity for people who are pregnant.

Kimberly Mutcherson is Professor of Law, Rutgers Law School in Camden. You can reach her by e-mail at kim.mutcherson@rutgers.edu.

[1] This short essay draws from a longer work-in-progress that I have written with the same title.

[2] Supreme Court opinions use various formulations to talk about embryonic and fetal life including liberal use of the phrase “potential life.” To the extent that potential life implies a life in formation and not a life in existence, I reject the notion that fetal life is not true life but only the possibility of life. I do not concede that this ends the discussion of whether abortion should be allowed. Instead, in the tradition of Judith Jarvis Thomson’s A Defense of Abortion, even if a fetus is a life or even a person, the question of when, if ever, a pregnant woman is obliged to preserve that life against her wishes remains open.

[3] The looseness of the term viability and its detachment from medical practice is a perennial problem in abortion jurisprudence.

![F/A-XX hints, icebreaker ambitions and previewing day two of Sea Air Space [VIDEO]](https://breakingdefense.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2025/04/250407_SAS_2025_indopac_WELCH-scaled-e1744076170241.jpg?#)