How Vauxhall lost its independence to Opel

Chevette, launched in the UK as a Vauxhall in 1975, was merely a renosed Opel Kadett Opel produced cars on the continent while Vauxhall built cars at Luton and Ellesmere Port Stellantis’s UK boss recently reassured us that Vauxhall has a future and reaffirmed that it legitimately is a British car brand – things that executives have had to do repeatedly for the half century since it was effectively subsumed into German manufacturer Opel. Vauxhall launched its first car in 1903, was bought by America’s General Motors in 1925 and in the 1960s became the UK’s third-largest car maker, with its old Luton home and new plant up at Ellesmere Port. Opel made its first car in 1899 and became a GM subsidiary in 1929. Post-war it grew to become Germany’s second-largest car maker, with a production total nearly five times higher than Vauxhall’s in 1969. Although both were owned by GM and shared parts, they were distinct from each other. Indeed, they operated in many of the same markets: Vauxhall was one of the UK’s major exporters (some 83,000 cars went as far afield as Ghana, Canada and Malaysia in 1968) and Opel was permitted to make a post-war return to the UK market in 1967, as the nation negotiated its entry into the European Common Market and Brits bought ever more foreign cars, and as “GM felt that Opel products do not duplicate the Vauxhall range too markedly”. It all started to go badly wrong for Vauxhall as the 1970s dawned. Ford was dominating sales more than ever before, while the character of Luton’s creations was best summed up by respected engineer Ralph Broad, who said: “How Opel can get it so right and Vauxhall can get it so wrong I shall never understand.” Productivity was terrible, too: Opel was Europe’s best performer in this regard, and Vauxhall was operating at just 59% of its level, losing production to rising costs and labour disputes. Although that problem was endemic: Ford in Dagenham was at 69% of Opel’s level, compared with 95% in Germany, while Leyland and Chrysler were at just 44% and 41%. Enjoy full access to the complete Autocar archive at the magazineshop.com Naturally, Vauxhall’s losses were soaring, too: from about £2 million in 1969 to almost £9.5m in 1970. It was an easy decision for GM, then, to consolidate developmental operations in Germany. So when the group’s first global platform was ready, responsibility for European ‘T-car’ development went to Opel, and the 1975 Vauxhall Chevette, although made in the UK, was merely a renosed and rebadged Opel Kadett – rendering the 1972 Victor the final genuine Vauxhall. With perhaps a hint of bitterness, we noted after Vauxhall launched a restyled Opel Ascona: “The Cavalier is not really a Vauxhall at all. But never mind. It will show on the statistics as one, although the 1972 Trade Descriptions Act requires it to have ‘Made in Belgium’ prominently displayed somewhere upon it. GM Europe president John McCormack (formerly of Opel) later explained to us: “All of our research and development work for cars is now regrouped in Germany. We are in no position to create a brand-new car in Britain. But we have a small team at Vauxhall charged with adapting Opel projects to the British market.” In 1979, we reported on the result of ‘Opelisation’: “Vauxhall went through what might be called, to put it mildly, a bad patch. The recovery achieved in the past four years has been little short of remarkable. It has swung back from a 7.4% UK share in 1975 to 8.2% of a much-increased market last year. “Some credit must be given for clever marketing. With still some resistance to any sort of imported car in this country, the acceptable Vauxhall name gave the advantage of concealing the origin of the cars.”Vauxhall’s boss agreed, telling us in 1983: “It turned out to be a good decision. We got our act together.” But there was also regret, as Luton East MP Graham Bright had expressed in 1981: “We have lost a tremendous number of skills. Unless there is the possibility of the design and engineering returning to Britain, those skills will disappear for ever. "We have also surrendered the European dealerships; Vauxhall cars are no longer permitted to be sold in Europe. "Within GM, in real terms, Vauxhall has been downgraded. Britain has lost the design capability and manufacturing experience that it needs. It is sad.”

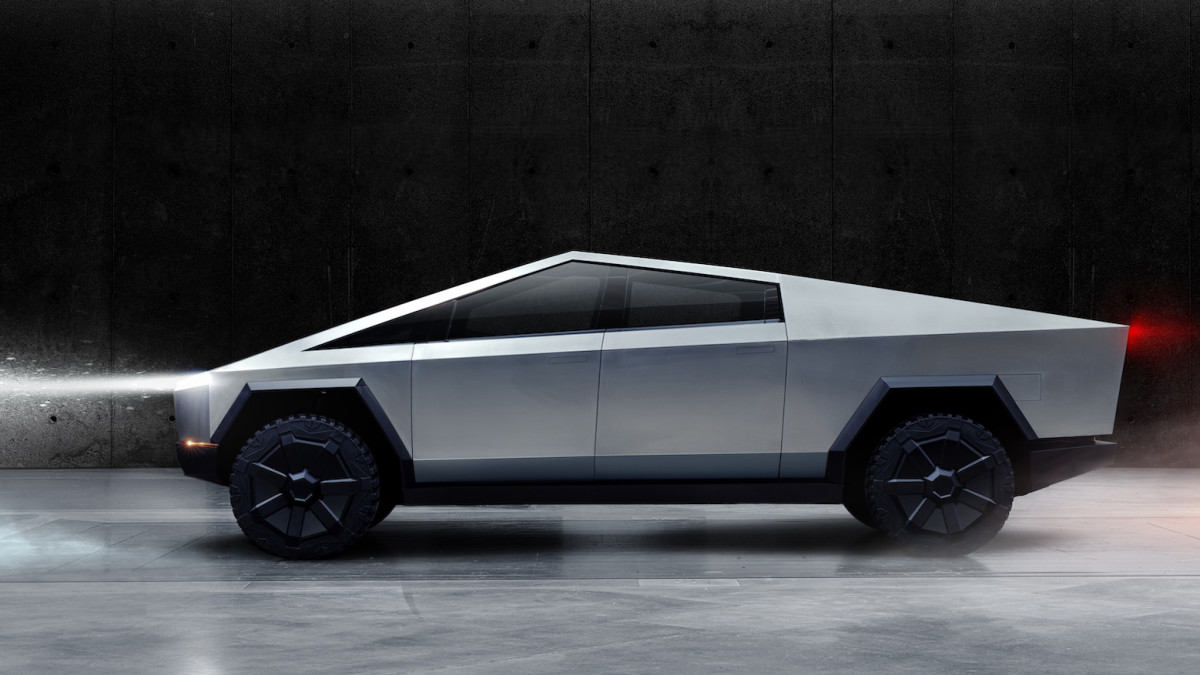

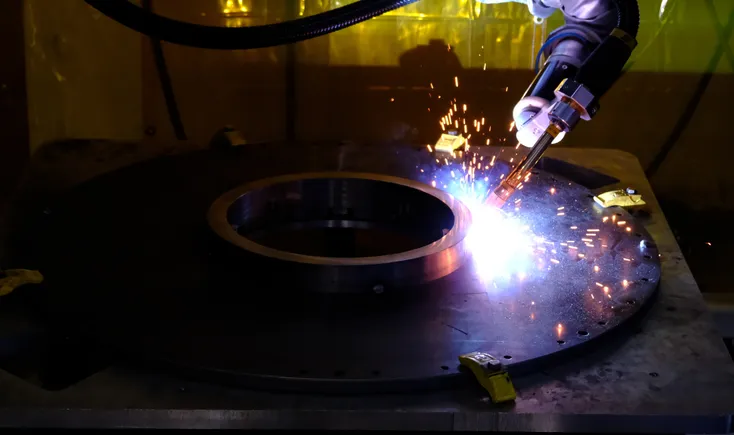

Chevette, launched in the UK as a Vauxhall in 1975, was merely a renosed Opel KadettOpel produced cars on the continent while Vauxhall built cars at Luton and Ellesmere Port

Stellantis’s UK boss recently reassured us that Vauxhall has a future and reaffirmed that it legitimately is a British car brand – things that executives have had to do repeatedly for the half century since it was effectively subsumed into German manufacturer Opel.

Vauxhall launched its first car in 1903, was bought by America’s General Motors in 1925 and in the 1960s became the UK’s third-largest car maker, with its old Luton home and new plant up at Ellesmere Port.

Opel made its first car in 1899 and became a GM subsidiary in 1929. Post-war it grew to become Germany’s second-largest car maker, with a production total nearly five times higher than Vauxhall’s in 1969.

Although both were owned by GM and shared parts, they were distinct from each other.

Indeed, they operated in many of the same markets: Vauxhall was one of the UK’s major exporters (some 83,000 cars went as far afield as Ghana, Canada and Malaysia in 1968) and Opel was permitted to make a post-war return to the UK market in 1967, as the nation negotiated its entry into the European Common Market and Brits bought ever more foreign cars, and as “GM felt that Opel products do not duplicate the Vauxhall range too markedly”.

It all started to go badly wrong for Vauxhall as the 1970s dawned. Ford was dominating sales more than ever before, while the character of Luton’s creations was best summed up by respected engineer Ralph Broad, who said: “How Opel can get it so right and Vauxhall can get it so wrong I shall never understand.”

Productivity was terrible, too: Opel was Europe’s best performer in this regard, and Vauxhall was operating at just 59% of its level, losing production to rising costs and labour disputes.

Although that problem was endemic: Ford in Dagenham was at 69% of Opel’s level, compared with 95% in Germany, while Leyland and Chrysler were at just 44% and 41%.

Enjoy full access to the complete Autocar archive at the magazineshop.com

Naturally, Vauxhall’s losses were soaring, too: from about £2 million in 1969 to almost £9.5m in 1970.

It was an easy decision for GM, then, to consolidate developmental operations in Germany.

So when the group’s first global platform was ready, responsibility for European ‘T-car’ development went to Opel, and the 1975 Vauxhall Chevette, although made in the UK, was merely a renosed and rebadged Opel Kadett – rendering the 1972 Victor the final genuine Vauxhall.

With perhaps a hint of bitterness, we noted after Vauxhall launched a restyled Opel Ascona: “The Cavalier is not really a Vauxhall at all. But never mind. It will show on the statistics as one, although the 1972 Trade Descriptions Act requires it to have ‘Made in Belgium’ prominently displayed somewhere upon it.

GM Europe president John McCormack (formerly of Opel) later explained to us: “All of our research and development work for cars is now regrouped in Germany. We are in no position to create a brand-new car in Britain. But we have a small team at Vauxhall charged with adapting Opel projects to the British market.”

In 1979, we reported on the result of ‘Opelisation’: “Vauxhall went through what might be called, to put it mildly, a bad patch. The recovery achieved in the past four years has been little short of remarkable. It has swung back from a 7.4% UK share in 1975 to 8.2% of a much-increased market last year.

“Some credit must be given for clever marketing. With still some resistance to any sort of imported car in this country, the acceptable Vauxhall name gave the advantage of concealing the origin of the cars.”Vauxhall’s boss agreed, telling us in 1983: “It turned out to be a good decision. We got our act together.”

But there was also regret, as Luton East MP Graham Bright had expressed in 1981: “We have lost a tremendous number of skills. Unless there is the possibility of the design and engineering returning to Britain, those skills will disappear for ever.

"We have also surrendered the European dealerships; Vauxhall cars are no longer permitted to be sold in Europe.

"Within GM, in real terms, Vauxhall has been downgraded. Britain has lost the design capability and manufacturing experience that it needs. It is sad.”

![What you need to know before you go to Sea Air Space 2025 [VIDEO]](https://breakingdefense.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2024/05/Screen-Shot-2024-05-14-at-12.19.19-PM.png?#)

.jpg)