How new technology is shaping the future of Mercedes-Benz

Markus Schafer oversees the research and development of every Mercedes model Tech boss Markus Schäfer says hybrid and electric technology is transforming everything "I have one of the most interesting jobs in the industry,” says Markus Schäfer with a smile, and even though he adds he’s “sometimes joking”, there’s absolute truth to his comment. His brief as chief technology officer of Mercedes-Benz is vast: effectively, he’s responsible for overseeing the research and development of every car that carries the three-pointed star. “That ranges from Formula 1 responsibilities with [Mercedes F1 power unit specialist] High Performance Powertrains to overseeing the entire research and development side of Mercedes-Benz Cars, turning ideas into real products of the future,” he says. “That’s a unique combination.” And that isn’t even Schäfer’s only job. He sits on the Mercedes-Benz Group board and is also responsible for procurement. “I’m in charge of purchasing around 40 to 50 billion components, depending on the year, that go into cars,” he says. “It’s busy these days.” Those would be daunting briefs in any era, let alone one in which Mercedes offers one of the largest and most diverse line-ups in the industry in both model types and powertrains. And on top of that there is the swirling uncertainty of electrification and shifting sands of legislation. Schäfer admits it is “very, very challenging”. He adds: “We don’t have a crystal ball, but we’re trying to anticipate what’s happening in the world and react accordingly when developing technology for this iconic brand. But what makes me confident is that we have a unique combination of different entities that no other company has. “We have Formula 1 and motorsports. We have AMG, we have Maybach and we have Mercedes-Benz. And we have substantial funds to invest in research. That gives me the freedom to work with a great team to develop cars that do more than move you from A to B.” To use such breadth as an advantage, though, it has to be harnessed. Espousing technology transfer is easily done, but actually taking knowledge gleaned from building hybrid F1 powertrains in Brixworth, UK, and applying it to EVs being developed in Stuttgart isn’t easy. So how does Schäfer do it? “It sounds a bit cheesy, but I’m a great believer in creating a learning organisation,” he says. “I’ve spent more than 30 years in this business as an engineer, mostly in this company, and I’ve learned you need to create a network of people that work extremely close together: no silos, no hierarchy. "What we’re doing is bringing all these global people – from China, Europe, the US, the UK – together to work as one team. “You have to learn from each other and share ideas. With the F1 team, we’re learning a lot because their turnaround time is measured in hours. "They don’t have time after a crash if they need to change the chassis or figure out an engine problem. That’s how they work. So we can learn speed: chasing milliseconds, continuous improvement, getting better every race.” Schäfer cites the Mercedes EQXX, the ultra-efficient road-legal electric hypermiler built to prove that a battery-powered car could top 1000km (620 miles) on a single charge, as one example of that collaboration: “Its development was led by the way the F1 team pushes the limits. It’s way more than headlines, technology transfer – and it also works the other way round.” To illustrate that point, Schäfer says Mercedes-Benz Cars has aided the F1 team through “foundational and fundamental research” in areas such as “the basics of processes such as combustion”. He adds: “Another area is batteries. In 2026, half an F1 powertrain will be electric, and the research Mercedes has done in batteries will help the F1 team.” The acknowledgement that Mercedes is still refining its combustion engines while also developing a whole new generation of fast-evolving electric powertrains points to the massive challenge that car firms currently face. And as much as Schäfer highlights how much Mercedes invests in R&D, it ultimately still has finite resources. “These days, the future seems even more uncertain because of the number of fields you’re playing in on the mechanical and electromechanical side, on software and electronics,” he says. “And our playing field is the world: we’re a global company, so it’s China, it’s Europe, it’s the US – and customer preferences and technology are not the same everywhere.” That can be seen in China’s love of extended-wheelbase saloons, and also screens. “They want bells and whistles on the digital side,” says Schäfer. “No buttons, only screens – give it to me. Conservative S-Class customers in Europe think differently.” That means “the differences between customers between regions are not converging: they’re getting bigger. So we have to develop different solutions. That doesn’t help efficiency, but successful products have to be tailored to the customer.” In recent years, of course, there has often be

Markus Schafer oversees the research and development of every Mercedes modelTech boss Markus Schäfer says hybrid and electric technology is transforming everything

"I have one of the most interesting jobs in the industry,” says Markus Schäfer with a smile, and even though he adds he’s “sometimes joking”, there’s absolute truth to his comment.

His brief as chief technology officer of Mercedes-Benz is vast: effectively, he’s responsible for overseeing the research and development of every car that carries the three-pointed star.

“That ranges from Formula 1 responsibilities with [Mercedes F1 power unit specialist] High Performance Powertrains to overseeing the entire research and development side of Mercedes-Benz Cars, turning ideas into real products of the future,” he says. “That’s a unique combination.”

And that isn’t even Schäfer’s only job. He sits on the Mercedes-Benz Group board and is also responsible for procurement. “I’m in charge of purchasing around 40 to 50 billion components, depending on the year, that go into cars,” he says. “It’s busy these days.”

Those would be daunting briefs in any era, let alone one in which Mercedes offers one of the largest and most diverse line-ups in the industry in both model types and powertrains.

And on top of that there is the swirling uncertainty of electrification and shifting sands of legislation. Schäfer admits it is “very, very challenging”.

He adds: “We don’t have a crystal ball, but we’re trying to anticipate what’s happening in the world and react accordingly when developing technology for this iconic brand.

But what makes me confident is that we have a unique combination of different entities that no other company has.

“We have Formula 1 and motorsports. We have AMG, we have Maybach and we have Mercedes-Benz. And we have substantial funds to invest in research. That gives me the freedom to work with a great team to develop cars that do more than move you from A to B.”

To use such breadth as an advantage, though, it has to be harnessed. Espousing technology transfer is easily done, but actually taking knowledge gleaned from building hybrid F1 powertrains in Brixworth, UK, and applying it to EVs being developed in Stuttgart isn’t easy. So how does Schäfer do it?

“It sounds a bit cheesy, but I’m a great believer in creating a learning organisation,” he says.

“I’ve spent more than 30 years in this business as an engineer, mostly in this company, and I’ve learned you need to create a network of people that work extremely close together: no silos, no hierarchy.

"What we’re doing is bringing all these global people – from China, Europe, the US, the UK – together to work as one team.

“You have to learn from each other and share ideas. With the F1 team, we’re learning a lot because their turnaround time is measured in hours.

"They don’t have time after a crash if they need to change the chassis or figure out an engine problem. That’s how they work. So we can learn speed: chasing milliseconds, continuous improvement, getting better every race.”

Schäfer cites the Mercedes EQXX, the ultra-efficient road-legal electric hypermiler built to prove that a battery-powered car could top 1000km (620 miles) on a single charge, as one example of that collaboration: “Its development was led by the way the F1 team pushes the limits. It’s way more than headlines, technology transfer – and it also works the other way round.”

To illustrate that point, Schäfer says Mercedes-Benz Cars has aided the F1 team through “foundational and fundamental research” in areas such as “the basics of processes such as combustion”.

He adds: “Another area is batteries. In 2026, half an F1 powertrain will be electric, and the research Mercedes has done in batteries will help the F1 team.”

The acknowledgement that Mercedes is still refining its combustion engines while also developing a whole new generation of fast-evolving electric powertrains points to the massive challenge that car firms currently face.

And as much as Schäfer highlights how much Mercedes invests in R&D, it ultimately still has finite resources.

“These days, the future seems even more uncertain because of the number of fields you’re playing in on the mechanical and electromechanical side, on software and electronics,” he says.

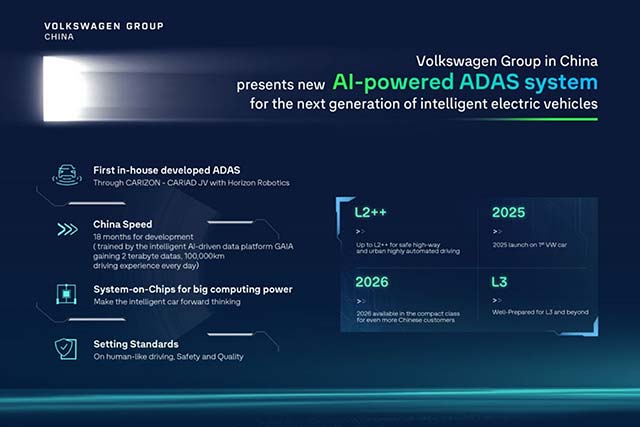

“And our playing field is the world: we’re a global company, so it’s China, it’s Europe, it’s the US – and customer preferences and technology are not the same everywhere.” That can be seen in China’s love of extended-wheelbase saloons, and also screens.

“They want bells and whistles on the digital side,” says Schäfer. “No buttons, only screens – give it to me. Conservative S-Class customers in Europe think differently.”

That means “the differences between customers between regions are not converging: they’re getting bigger. So we have to develop different solutions. That doesn’t help efficiency, but successful products have to be tailored to the customer.”

In recent years, of course, there has often been a divide between the cars customers want and the cars legislators want them to want.

So flexibility is vital, as seen by Mercedes’ decision to pivot and offer the planned EV-only next-gen CLA with mild-hybrid powertrains as well.

“We’re moving from a mechanical world of combustion engines to a world which is electric, digital and autonomous,” says Schäfer. “It’s happening at different speeds and being driven by regulations and geopolitics. We wish for stable regulations but this is not something we have. So the answer is flexibility.

“The ultimate proof is the customer’s choice: in the end, the customer decides what to buy. So we have to tailor the right product for the right customers, and if we show the benefit of new technology, the customer will buy it.

The end goal is clear for us: it’s the electric car, because it’s the most efficient way of transforming energy into movement, and a great tool for carbon reduction.

“But you don’t have to force the customer: you have to convince the customer this is a great choice, because it’s a desirable car, it’s great aesthetics, it’s emotional and there’s a business case. The CLA can do 12kWh/100km [5.1mpkWh] so it can be a great economical benefit.”

The CLA’s efficiency means that it will offer more than 400 miles of range as an EV, which, notes Schäfer, is “a huge step for an entry-level car”. That efficiency has been hard-won: “Three years ago, I established an efficiency department that does nothing but drill into the last bits and bytes that impact the efficiency of a car.

“We’ve looked at wind resistance, aerodynamics, the rolling resistance of tyres and every moving part. We looked at heating and cooling, and at the electric motor.

"That’s driven us to develop our own motors, because we thought we can do better. So instead of having one gear, let’s have two gears to decouple in a four-wheel-drive car, so if you don’t need one motor, it’s intelligently switched off.”

The CLA will be the first car on Mercedes’ new MMA platform, created for compact cars. The firm is also developing a new platform for medium-sized EVs and a bespoke performance architecture for future AMG models.

But in an era when software is increasingly important, what exactly is a car platform these days?

“In the era of EVs and autonomous cars, we have to rethink platforms and architectures because we’ve completely changed the way we create cars. In the old days, you’d start with a shell. Now you start from your operating system.

“You start with software and electronics. You design the layout of your ECUs and how data is distributed around the car, which depends on the sensor set and actuators you have.

This is the starting point: zone architecture, domain architecture, how many gigabits you want to transfer, how many teraflops the car needs to operate. Then how many cameras, radars and light pixels you need.

“We’ve made it modular so we have one software architecture, MB.OS, which we’ll see first with the MMA cars. It will be in every Mercedes car, van and AMG. We’ll scale it over two, three million cars.

“The second element of the platform is the powertrain: modular drivetrains, modular batteries, modular e-motors. And then, later on, you put a shell around it, a nice, beautiful aesthetic shell designed by [Mercedes design chief] Gorden Wagener. But that’s the last part.”

Schäfer describes the shift of every future model to a single operating system as “a game-changer”, not least in how it has changed development.

In the past, Mercedes would buy control units and chips from suppliers and then “put them together in a spaghetti diagram”. But now “we are the architects” defining the entire layout.

In turn, that means Mercedes can more rapidly achieve “very, very big scale” with reduced complexity and – a bonus for the guy in charge of procurement – with “better supply chain resilience”.

It’s a big step, though, and rivals such as the Volkswagen Group and Volvo have struggled with making the transition to software-defined vehicles.

Schäfer says that success for Mercedes will come back to culture: “We have software and hardware people sitting next to each other, because a car is a super-integrated product.

"We’ve brought in lots of people from the software industry who have different methods of working, and with our culture of working together, we have absolute respect in implementing that.”

There’s another aspect to the challenge as well: while Mercedes is breaking in to new technology, it still has more than 130 years of heritage to live up to. This is the firm, after all, that pioneered the combustion engine.

“There’s a foundation this brand is carried on that should not change,” says Schäfer. “There’s fundamental pillars, trust in the brand. A Mercedes is always known for quality.

“Safety is a key pillar for us, which will never change, and so is desirability. It’s the aesthetics, beautiful proportions, details, craftsmanship.

"And it’s always been about technology. We’ll never give up the core elements that created one of the most valuable brands in the world.”