This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

All

Autoblog

Autocar RSS Feed

Automotive News Breaking News Feed

Automotive World

Autos

Electric Cars Report

Jalopnik

Automotive News | AM-online

Speedhunters

The Truth About Cars

Porsche has been manufacturing in Zuffenhause...

Apr 2, 2025 0

Cupra continues to redefine customer experien...

Apr 2, 2025 0

Renault Grand Koleos equipped with Valeo Smar...

Apr 2, 2025 0

Toyota maintains top automotive spot in annua...

Apr 2, 2025 0

All

All Stories

All Stories

BioPharma Dive - Latest News

Breaking World Pharma News

Drugs.com - Clinical Trials

Drugs.com - FDA MedWatch Alerts

Drugs.com - New Drug Approvals

Drugs.com - Pharma Industry News

FDA Press Releases RSS Feed

Federal Register: Food and Drug Administration

News and press releases

Pharmaceuticals news FT.com

PharmaTimes World News

Stat

What's new

Preclinical study: after heart attack, a boos...

Mar 30, 2025 0

Enzyme engineering opens door to novel therap...

Mar 30, 2025 0

New tool to boost cancer immunotherapy effects

Mar 27, 2025 0

All

Breaking DefenseFull RSS Feed – Breaking Defense

DefenceTalk

Defense One - All Content

Military Space News

NATO Latest News

The Aviationist

War is Boring

War on the Rocks

NATO Defence College Field Studies Visit to N...

Apr 2, 2025 0

The Ukraine Defence Contact Group to meet at ...

Apr 2, 2025 0

The Coalition of the Willing Defence Minister...

Apr 2, 2025 0

NATO Deputy Secretary General to visit Poland

Apr 2, 2025 0

All

Advanced Energy Materials

CleanTechnica

Energy | FT

Energy | The Guardian

EnergyTrend

Nature Energy

NYT > Energy & Environment

PV-Tech

RSC - Energy Environ. Sci. latest articles

Utility Dive - Latest News

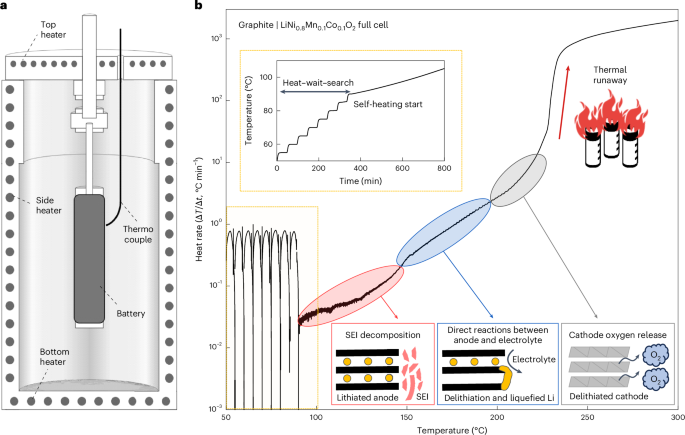

Toward Realistic Full Cells with Protected Li...

Apr 2, 2025 0

Theoretical and Experimental Optimization of ...

Apr 2, 2025 0

Interfacial Challenges of Halide‐Based All‐So...

Apr 2, 2025 0

Single Crystal Sodium Layered Oxide Achieves ...

Apr 2, 2025 0

Publisher Correction: Navigating thermal stab...

Mar 28, 2025 0

Rate matters

Mar 25, 2025 0

Amine oxides step up

Mar 25, 2025 0

- Contact

- Agriculture

- Automotive

- Beauty

-

Biopharma

- All

- All Stories

- All Stories

- BioPharma Dive - Latest News

- Breaking World Pharma News

- Drugs.com - Clinical Trials

- Drugs.com - FDA MedWatch Alerts

- Drugs.com - New Drug Approvals

- Drugs.com - Pharma Industry News

- FDA Press Releases RSS Feed

- Federal Register: Food and Drug Administration

- News and press releases

- Pharmaceuticals news FT.com

- PharmaTimes World News

- Stat

- What's new

- Defense

- Energy & Water

- Fashion

- Food & Beverage

- Healthcare

- Legal

- Manufacturing

- Luxury

- Medical Devices

- Mining

- Real Estate

- Retail

- Science Journals

- Transport & Logistics

- Travel & Hospitality