Where are they now? Andrew Barr’s life after wine writing

Once the enfant terrible of wine journalism, Andrew Barr has found a new life far from the tasting rooms of the past. From controversial critic to political campaigner, his journey is as compelling as the stories he once told. The post Where are they now? Andrew Barr’s life after wine writing appeared first on The Drinks Business.

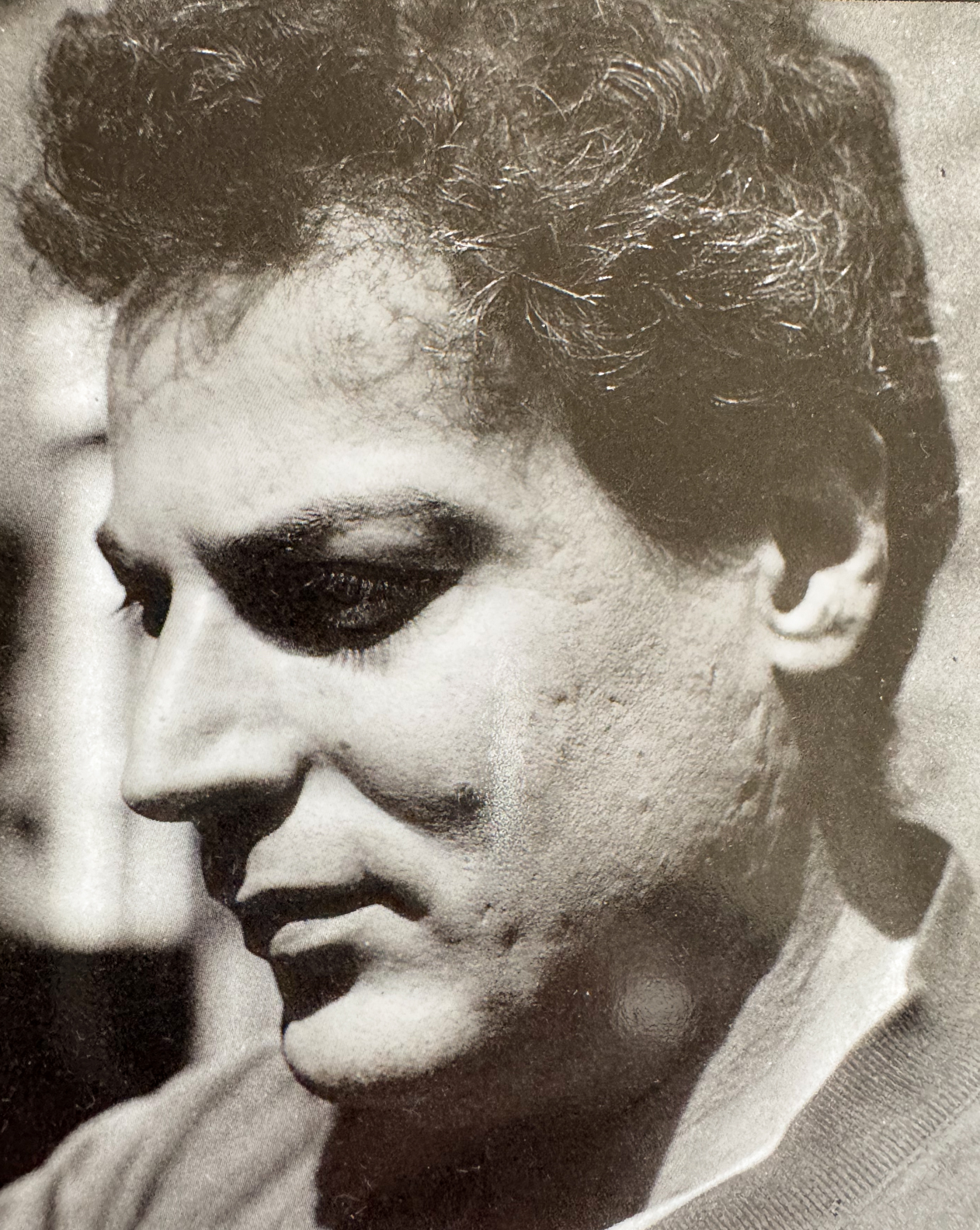

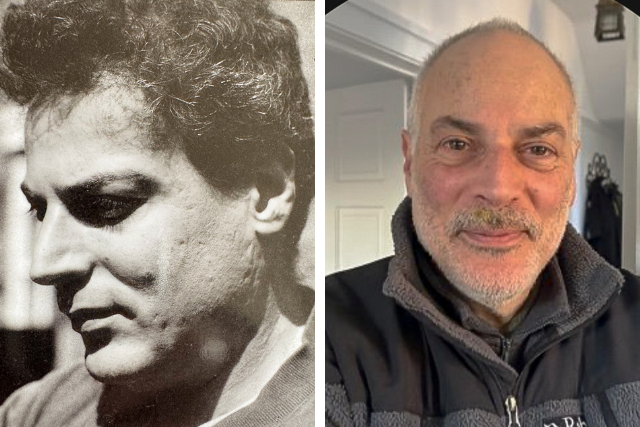

Andrew Barr was wearing a suit and tie, topped off by a yarmulke under a trilby when I caught up with him in London. I don’t recall Andrew once wearing a suit or tie, let alone a yarmulke, in all the time I knew him as a wine writer. Not having seen or heard of Andrew since the days of The Octagon (the Young Turks of the wine press set up in opposition to the Circle of Wine Writers) for at least two decades, this persona came as a bit of a shock. Other than that, and the loss of a good deal of hair, he looked and sounded remarkably similar to when he was branded the enfant terrible of wine for his controversial book, Wine Snobbery.

Wine Snobbery, an Insider’s Guide to the Booze Business, was written in 1987 when Andrew was 26 and published the following year. It emerged from his reviewing a book about pesticide residues in wine and coincided with the 1985 so-called antifreeze (diethylene glycol) scandal in Austria. "I was hacked off by the attitude of the wine trade who were doing their best to sweep it under the carpet. I didn’t realise quite how the world worked and thought it was the job of the journalist to expose the truth."

The focus of Wine Snobbery was satirising the many shibboleths accompanying wine and wine trade malpractices. The extent of his knowledge of the wine trade and more widely, the wine industry would be remarkable for a man twice his age. Dare I suggest it, it repays re-reading, or reading if you haven’t come across it before for its astonishing attention to detail. At a time when English wine was still considered something of a bad joke, he predicted: "When the bottle-fermented English sparkling wines which are presently being developed are put on the market, it may be demonstrated that champagnes are not necessarily superior."

Andrew Barr was wearing a suit and tie, topped off by a yarmulke under a trilby when I caught up with him in London. I don’t recall Andrew once wearing a suit or tie, let alone a yarmulke, in all the time I knew him as a wine writer. Not having seen or heard of Andrew since the days of The Octagon (the Young Turks of the wine press set up in opposition to the Circle of Wine Writers) for at least two decades, this persona came as a bit of a shock. Other than that, and the loss of a good deal of hair, he looked and sounded remarkably similar to when he was branded the enfant terrible of wine for his controversial book, Wine Snobbery.

Wine Snobbery, an Insider’s Guide to the Booze Business, was written in 1987 when Andrew was 26 and published the following year. It emerged from his reviewing a book about pesticide residues in wine and coincided with the 1985 so-called antifreeze (diethylene glycol) scandal in Austria. "I was hacked off by the attitude of the wine trade who were doing their best to sweep it under the carpet. I didn’t realise quite how the world worked and thought it was the job of the journalist to expose the truth."

The focus of Wine Snobbery was satirising the many shibboleths accompanying wine and wine trade malpractices. The extent of his knowledge of the wine trade and more widely, the wine industry would be remarkable for a man twice his age. Dare I suggest it, it repays re-reading, or reading if you haven’t come across it before for its astonishing attention to detail. At a time when English wine was still considered something of a bad joke, he predicted: "When the bottle-fermented English sparkling wines which are presently being developed are put on the market, it may be demonstrated that champagnes are not necessarily superior."

.jpg)