This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

All

Autoblog

Autocar RSS Feed

Automotive News Breaking News Feed

Automotive World

Autos

Electric Cars Report

Jalopnik

Automotive News | AM-online

Speedhunters

The Truth About Cars

All-new 2026 Hyundai Palisade SUV makes “Bigg...

Apr 16, 2025 0

Lotus Technology to acquire 51% equity intere...

Apr 16, 2025 0

All-new 2026 Hyundai Palisade SUV makes “Bigg...

Apr 16, 2025 0

Lotus Technology to acquire 51% equity intere...

Apr 16, 2025 0

Subaru reveals all-new, all-electric 2026 Tra...

Apr 16, 2025 0

All-new 2026 Subaru Solterra EV debuts update...

Apr 16, 2025 0

All

All Stories

All Stories

BioPharma Dive - Latest News

Breaking World Pharma News

Drugs.com - Clinical Trials

Drugs.com - FDA MedWatch Alerts

Drugs.com - New Drug Approvals

Drugs.com - Pharma Industry News

FDA Press Releases RSS Feed

Federal Register: Food and Drug Administration

News and press releases

Pharmaceuticals news FT.com

PharmaTimes World News

Stat

What's new

Potential Alzheimer's disease therapeuti...

Apr 13, 2025 0

New study reveals how tumors hijack key nutri...

Apr 10, 2025 0

Alternative approach to Lyme disease vaccine ...

Apr 10, 2025 0

Researchers find key to treating painful dry ...

Apr 10, 2025 0

All

Breaking DefenseFull RSS Feed – Breaking Defense

DefenceTalk

Defense One - All Content

Military Space News

NATO Latest News

The Aviationist

War is Boring

War on the Rocks

Military Committee in Chiefs of Defence Session

Apr 16, 2025 0

Joint press statement

Apr 16, 2025 0

Military Committee in Chiefs of Defence Session

Apr 16, 2025 0

Joint press statement

Apr 16, 2025 0

NATO reaffirms its steadfast commitment to se...

Apr 15, 2025 0

NATO Deputy Secretary General meets the Chair...

Apr 15, 2025 0

All

Advanced Energy Materials

CleanTechnica

Energy | FT

Energy | The Guardian

EnergyTrend

Nature Energy

NYT > Energy & Environment

PV-Tech

RSC - Energy Environ. Sci. latest articles

Utility Dive - Latest News

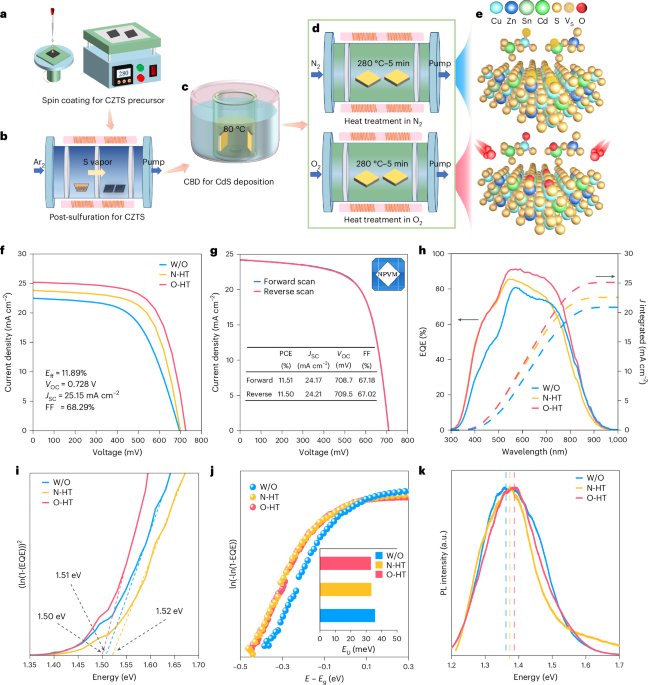

Streamlined Phase Transition and Reaction Com...

Apr 16, 2025 0

Streamlined Phase Transition and Reaction Com...

Apr 16, 2025 0

Combined In Situ X‐Ray Spectroscopic and Theo...

Apr 16, 2025 0

Engineering Ruthenium Species on Metal–organi...

Apr 16, 2025 0

Structural Unpredictability of a Cobalt‐Free ...

Apr 16, 2025 0

- Contact

- Agriculture

- Automotive

- Beauty

-

Biopharma

- All

- All Stories

- All Stories

- BioPharma Dive - Latest News

- Breaking World Pharma News

- Drugs.com - Clinical Trials

- Drugs.com - FDA MedWatch Alerts

- Drugs.com - New Drug Approvals

- Drugs.com - Pharma Industry News

- FDA Press Releases RSS Feed

- Federal Register: Food and Drug Administration

- News and press releases

- Pharmaceuticals news FT.com

- PharmaTimes World News

- Stat

- What's new

- Defense

- Energy & Water

- Fashion

- Food & Beverage

- Healthcare

- Legal

- Manufacturing

- Luxury

- Medical Devices

- Mining

- Real Estate

- Retail

- Science Journals

- Transport & Logistics

- Travel & Hospitality