Thwarting Tehran by creating prosperity in Africa

Strategic military and economic engagement with African nations can help weaken US adversaries while promoting economic interests, writes Ethan Tan of the America First Policy Institute.

Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamanei attends an event in Tehran, Iran on May 10, 2025. (Photo by IRANIAN LEADER PRESS OFFICE/Anadolu via Getty Images)

President Donald Trump’s historic visit to the Middle East, the first planned overseas visit of his second term, focused on deepening commercial and cultural ties — investments that not only increase mutual prosperity but also send a strong message to adversaries that their tactics and ambitions will not work.

A similar opportunity exists across Africa, where America’s adversaries are both a present and future danger to US interests. Investing smartly in Africa could lead to wins, both economic and in terms of national security, for the administration.

While the continent has perhaps understandably taken a back seat to urgent crises in other parts of the world, Africa has long been the focus of adversarial regimes in Moscow and Beijing. Since 2017, both China and Russia have maintained a significant presence in the region. China’s military maintains a key support base in Djibouti, while Russian-contracted private military contractors (PMCs) have a well-established presence in Djibouti, Sudan, the Central African Republic, Somalia, and Mali.

Meanwhile, seeing its foothold in the nearby Middle East diminish, the Iranian regime is already looking to Africa to rebuild its empire of terror, with the hope that the United States and its partners will not notice.

Despite the Houthis waving the white flag following US airstrikes, Iran has initiated a Houthi alliance with Somalia based group Al-Shabaab. Tehran is utilizing their intelligence networks imbedded with the Sudanese government and the IRGC Quds Force’s Unit 400 to disrupt American counterterrorism and economic interests on the turf of our regional ally, Kenya. This geographic shift is a significant pivot by the Iranian regime and is an affirmation they are now seeking more promising pastures after their territorial losses across the Middle East over the last 18 months.

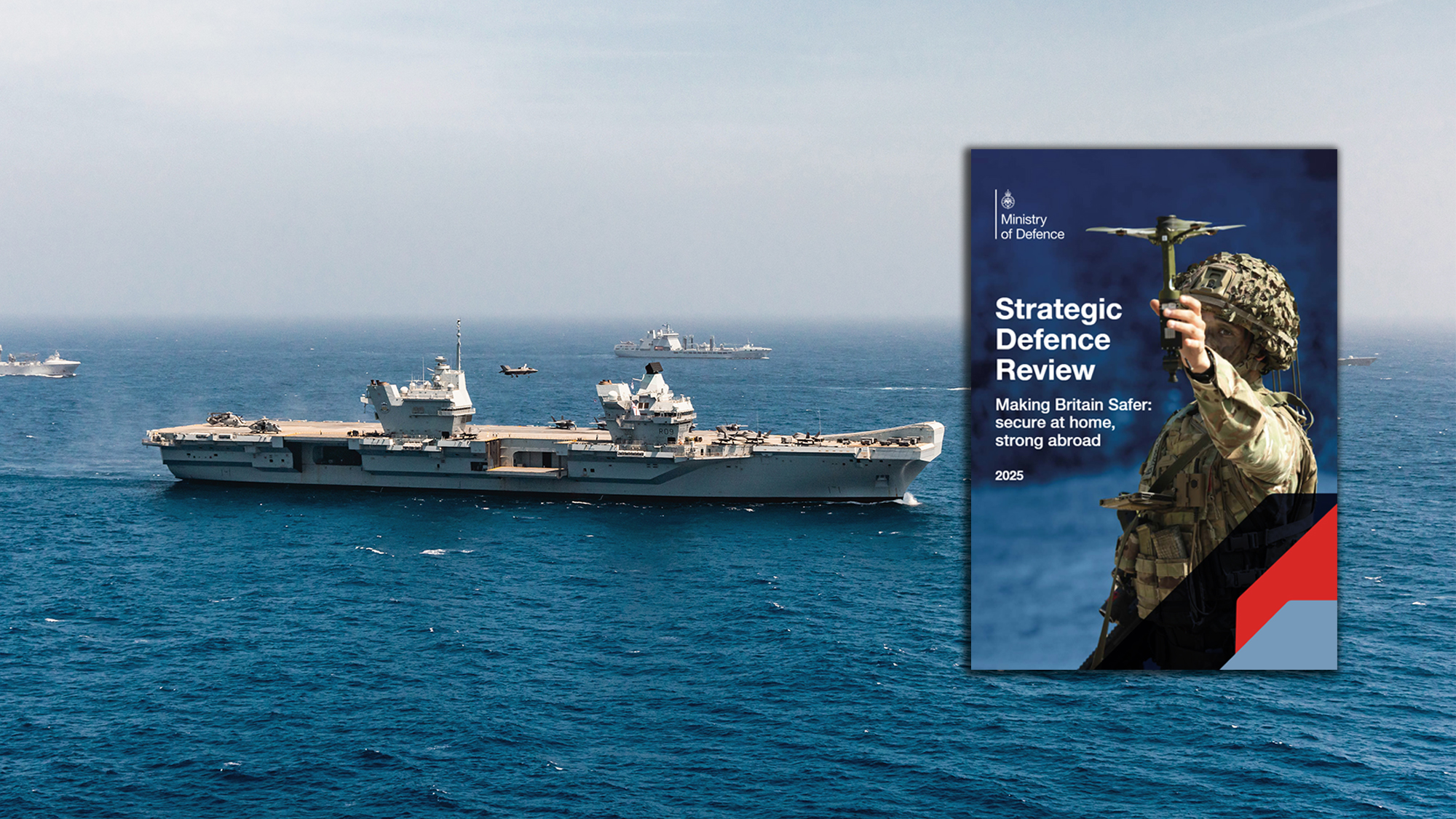

While a US military response will always have a role in the region — look at the significant US counterterrorism successes of Trump administration’s first 100 days in Somalia and in the Red Sea — a parallel economic approach has unique long-term advantages in rebuilding trust and enduring partnerships.

Building on the innovative approach of the Trump administration’s first term, an America First approach to engagement in Africa depends on identifying and capitalizing on economic partnerships, especially through investing in local economies. This investment in prosperity on the continent not only builds new commercial opportunities for its citizens as well as the United States but also prevents our adversaries from tapping into coveted resource pools.

Naturally, given the different circumstances of African nations from those of our Gulf partners, those economic opportunities may look different from the historic investments in the United States that the president secured during his Middle East visit. While most African countries do not have the financial capital to strike trade deals worth over $100 billion, they do have swaths of natural resources that can be tapped into.

Investments into the Lobito Corridor, which connects the resource-rich DRC and Zimbabwe to Angola’s Atlantic ports and from there the larger global markets, and the proposed Nigeria-Morocco gas pipeline, are opportunities not only to deepen partnerships with African countries but to do so while advancing American interests.

Africa’s youth unemployment rate currently sits at 32.9 percent, making the continent a hot bed for terror groups looking to recruit desperate young people. Moreover, over 73 percent of voluntary recruits to Al-Shabaab and Boko Haram noted that the inability of the government to provide employment opportunities as one of the primary drivers behind recruiting interests. The combination of these statistics points to a lack of infrastructure in stopping not just terrorists but our adversaries.

Therefore, strategic US engagement with nations in the region not only provides an opportunity to weaken our adversaries but also to promote economic partnership. With Kenya’s recent ascension to a major non-NATO ally of the US we must bolster our coordination with them to first confront the terror threats but then to help provide the infrastructure needed to bolster industrial development.

Again, military action is likely inevitable.

The Horn of Africa contains maritime lanes critical to trade between Europe and Asia, such as the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, the Gulf of Aden, and the Suez Canal. Current US military installations around the strait promote global trade by deterring terrorism and piracy. To keep these lanes open, shows of force against aggression — efforts like the targeted strikes on the Houthis and on terrorists in Somalia, and recent US strikes on Al-Shabab — should continue as needed to eliminate specific existing or emerging threats.

But military action alone is not the solution in Africa.

Iran thrives when it’s able to peddle its influence abroad through regional actors, and unstable regimes in Africa are prime candidates as they are willing to exchange regional influence for security guarantees.

Through an increased emphasis on not only regional security but also mutually beneficial economic partnerships, the Trump administration can open a new chapter for Africa that benefits its people as well as the American people.

Ethan Tan serves as a Policy Analyst for American Security at the America First Policy Institute.