This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

All

Autoblog

Autocar RSS Feed

Automotive News Breaking News Feed

Automotive World

Autos

Electric Cars Report

Jalopnik

Automotive News | AM-online

Speedhunters

The Truth About Cars

Isuzu: The announcement of financial informat...

May 14, 2025 0

Pony AI Inc. announces voluntary extended loc...

May 14, 2025 0

Plus completes successful test of semi-autono...

May 14, 2025 0

Iteris chosen to implement the City of Burles...

May 14, 2025 0

All

All Stories

All Stories

BioPharma Dive - Latest News

Breaking World Pharma News

Drugs.com - Clinical Trials

Drugs.com - FDA MedWatch Alerts

Drugs.com - New Drug Approvals

Drugs.com - Pharma Industry News

FDA Press Releases RSS Feed

Federal Register: Food and Drug Administration

News and press releases

Pharmaceuticals news FT.com

PharmaTimes World News

Stat

What's new

Unlocking a new era in liver cancer treatment...

May 12, 2025 0

Fungi dwelling on human skin may provide new ...

May 12, 2025 0

A candidate drug dismantles a metabolic barri...

May 12, 2025 0

FDA Approves Arbli (losartan potassium) Oral ...

May 12, 2025 0

FDA Approves Pembrolizumab for HER2 Positive ...

May 12, 2025 0

All

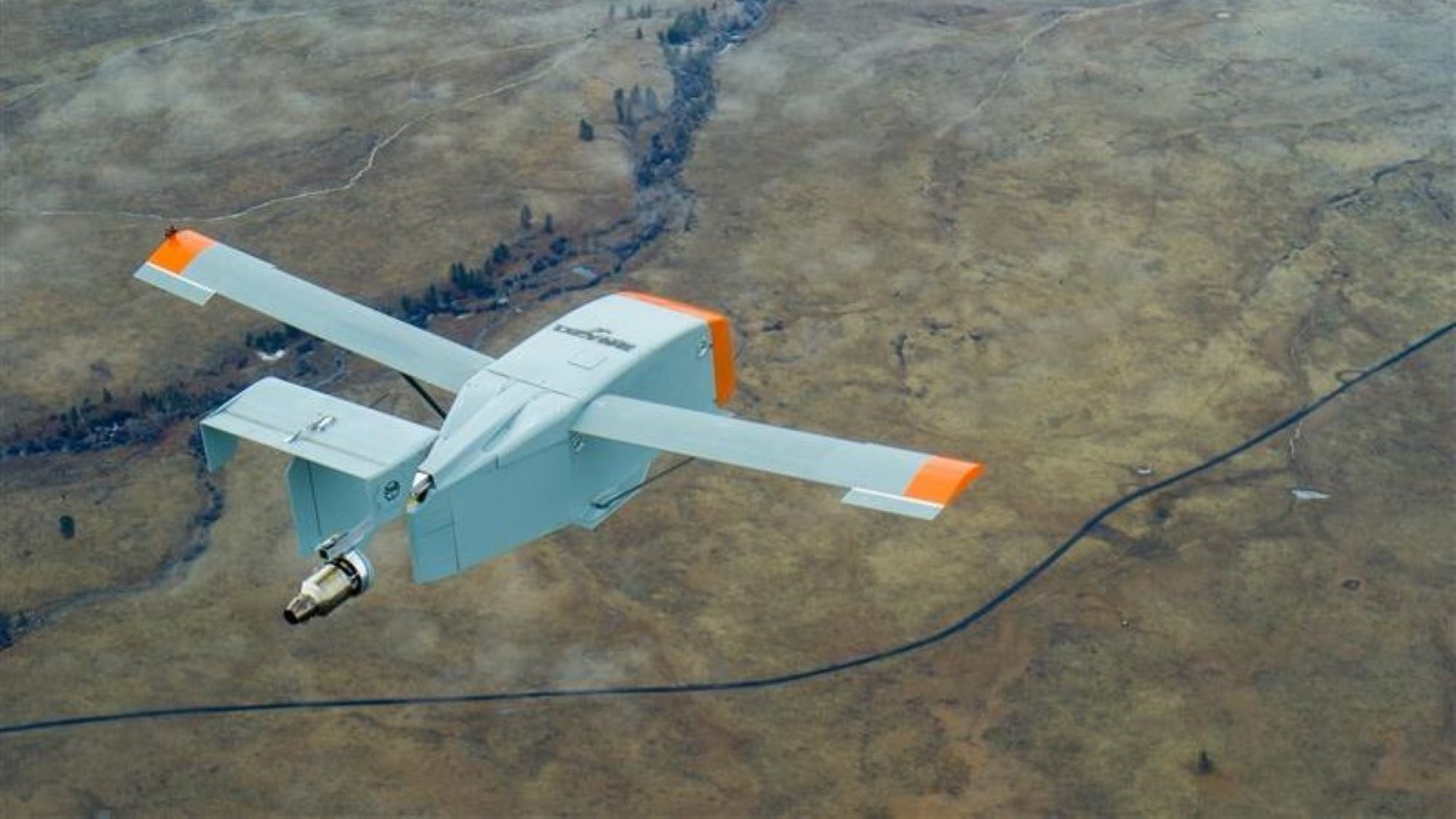

Breaking DefenseFull RSS Feed – Breaking Defense

DefenceTalk

Defense One - All Content

Military Space News

NATO Latest News

The Aviationist

War is Boring

War on the Rocks

NATO Chiefs of Defence meet in Brussels

May 14, 2025 0

The United Kingdom takes the lead of NATO’s T...

May 13, 2025 0

NATO hosts Colombian Chief of Defence

May 13, 2025 0

Chair of the NATO Military Committee visits t...

May 12, 2025 0

All

Advanced Energy Materials

CleanTechnica

Energy | FT

Energy | The Guardian

EnergyTrend

Nature Energy

NYT > Energy & Environment

PV-Tech

RSC - Energy Environ. Sci. latest articles

Utility Dive - Latest News

An In Situ Polymerized Solid‐State Electrolyt...

May 14, 2025 0

High‐Performing Perovskite/Ruddlesden‐Popper ...

May 14, 2025 0

Lattice Plainification and Intercalation Adva...

May 14, 2025 0

VS2/Bi2S3 Spring‐Type Heterointerfaces Hollow...

May 14, 2025 0

Understanding non-compliance

May 12, 2025 0

Author Correction: H<sub>2</sub> and CO<sub>2...

May 12, 2025 0

- Contact

- LIVE TV

- Agriculture

- Automotive

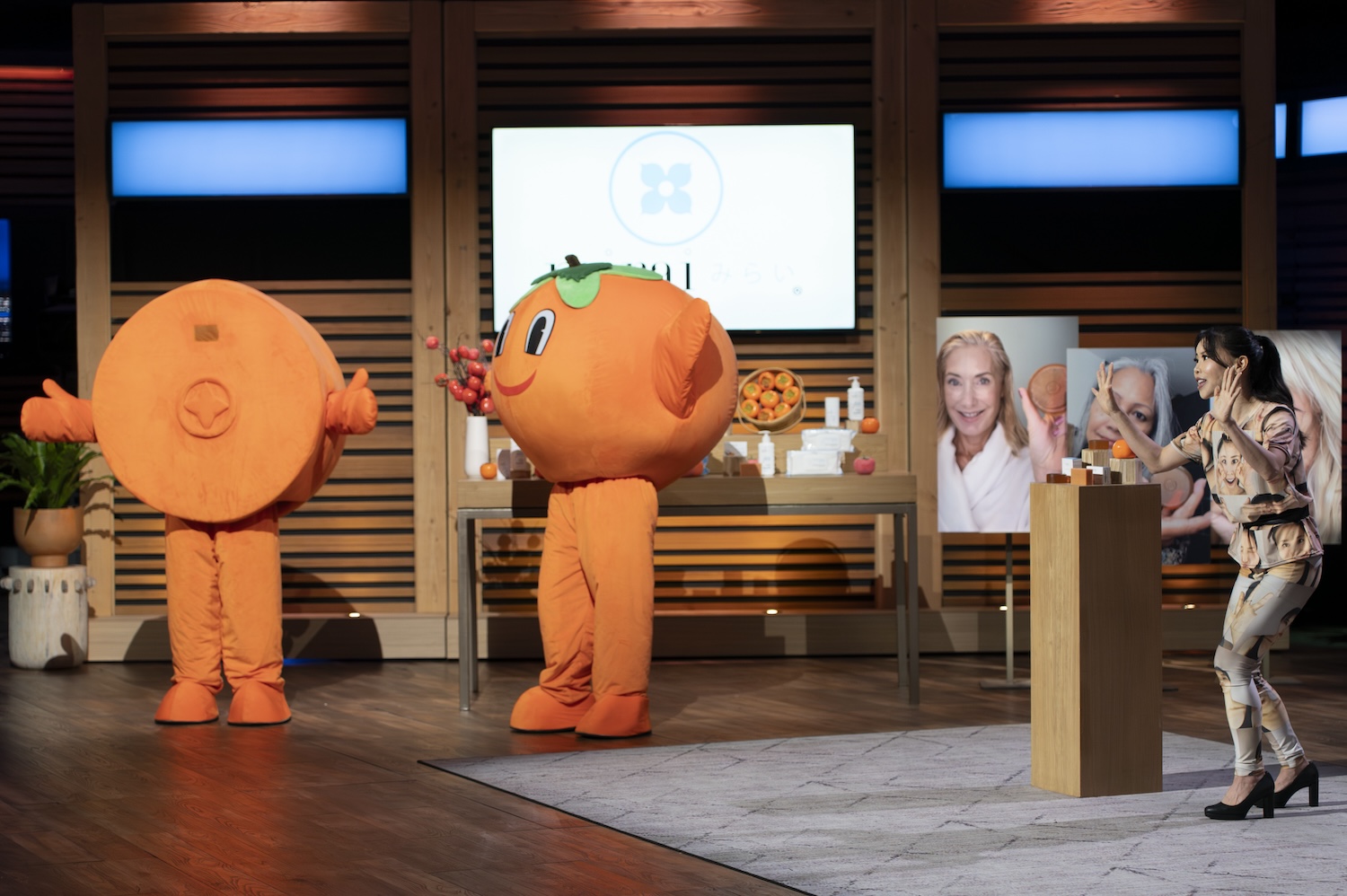

- Beauty

-

Biopharma

- All

- All Stories

- All Stories

- BioPharma Dive - Latest News

- Breaking World Pharma News

- Drugs.com - Clinical Trials

- Drugs.com - FDA MedWatch Alerts

- Drugs.com - New Drug Approvals

- Drugs.com - Pharma Industry News

- FDA Press Releases RSS Feed

- Federal Register: Food and Drug Administration

- News and press releases

- Pharmaceuticals news FT.com

- PharmaTimes World News

- Stat

- What's new

- Defense

- Energy & Water

- Fashion

- Food & Beverage

- Healthcare

- Legal

- Manufacturing

- Luxury

- Medical Devices

- Mining

- Real Estate

- Retail

- Science Journals

- Transport & Logistics

- Travel & Hospitality