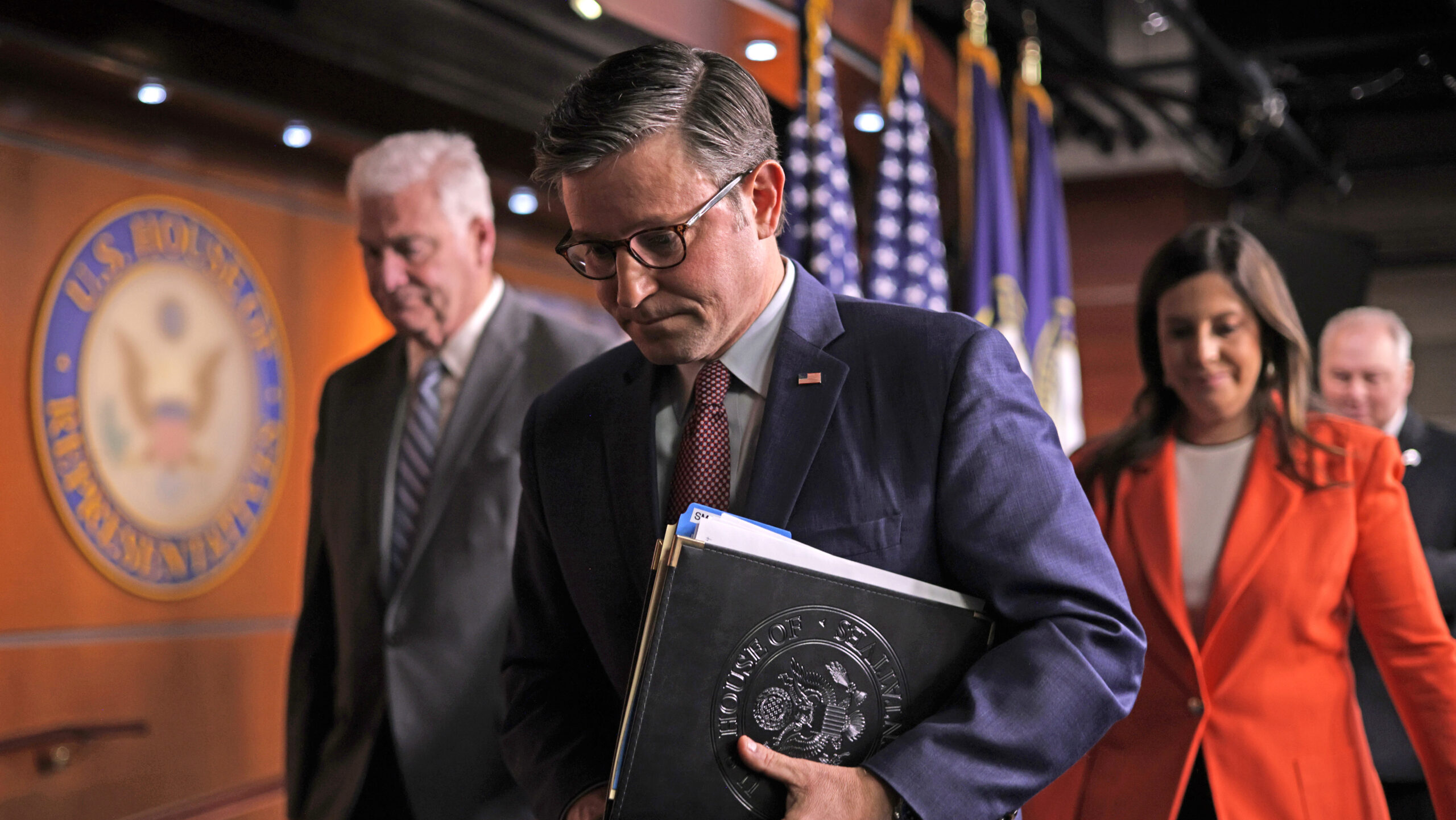

Eric Adams Gets Helpful Assist From Paul Clement

Bigshot litigator recommends letting Adams walk with even more than Trump offered. The post Eric Adams Gets Helpful Assist From Paul Clement appeared first on Above the Law.

Judge Dale Ho asked the conservative movement’s top Supreme Court advocate, Paul Clement, to weigh in on the Trump administration’s decision to dismiss its case against NYC Mayor Eric Adams without prejudice. Judge Ho harbored understandable concerns when the decision from DOJ leadership prompted everyone who ever saw the evidence in the case to resign or avoid any record of involvement with the decision like the plague. As it happens, the federal courts have a procedure for dealing with prosecutors trying to abuse their power to kill prosecutions for political reasons, and that is to require dismissals secure leave of the court.

Thankfully, when he’s not busy whining that law firms don’t support killing kids enough, Clement is available to provide independent insights on “leave of court” decisions and Judge Ho tasked him to review the Adams case. Because, remember, any time a Democrat needs an independent review of a case with political overtones, they must pick the most conservative person available. And when a Republican needs an independent review of a case with political overtones, they must also pick the most conservative person available.

In this case though, Judge Ho sorta placed Clement’s balls in vise, forcing a lawyer whose book of business is tied up in MAGA causes to either call out the thin-skinned and vengeful administration for embarking on an amnesty-for-favors campaign so offensive that multiple prosecutors resigned over it or make the bad faith argument that this was all copasetic (hey, it works for law professors!).

Clement somehow chose a third path greenlighting the dismissal while balking at the DOJ’s intended “without prejudice” posture. In other words, Trump can let Adams off for foreign bribes but he can’t hold it over the mayor’s head — as Trump border czar Tom Homan accidentally confessed was the plan all along.

But it’s still very, very stupid:

Thus, where the publicly available materials are sufficient to support dismissal with prejudice, there is no need for further inquiry. Here, the publicly available materials—and the basic dynamic of a federal prosecution of a popularly elected public official—counsel in favor of dismissal with prejudice.

Ahem… no, they fucking don’t. The publicly available materials are so damning that they’ve written a musical number about it. And that’s just the publicly available stuff. The stuff that isn’t in the public is so bad that multiple high-ranking Justice Department officers QUIT over this decision.

Not for nothing, this case involves deleted material too, making the uncritical reliance on “publicly available” evidence all the more disingenuous.

Importantly, the Court expressly endorsed a judicial inquiry that goes beyond the four corners of the government’s motion to dismiss. In fact, the Court based its ultimate disposition—reversing the Fifth Circuit and upholding the government’s effort to dismiss the indictment—on “[o]ur examination of the record.” Id. at 30. The Court also confirmed that it would not presume bad faith on the part of the government, and that “[t]he salient issue” is not whether the decision to initiate the prosecution “was made in bad faith but rather whether the Government’s later efforts to terminate the prosecution were similarly tainted with impropriety.”

Yes, but not presuming bad faith is not the same as precluding any chance of bad faith. Might something have happened here to lead a judge — or the judge’s appointed reviewer — to reach a finding of bad faith?

The filing of that motion precipitated a series of resignations and unusual public disclosures concerning internal deliberations about the case and the decision to seek dismissal. While some of the materials became public outside official channels, other statements were made through official channels. Suffice it to say that those materials raised material questions concerning both the initial decision to pursue the indictment and the subsequent decision to seek dismissal.

This will be the first and last explicit mention of the relevant facts in this inquiry. From here on, the case is described as though it’s utterly routine.

This is such a case. Here, the materials that have already been made public provide ample reasons to order dismissal with prejudice. The government’s own recent filings reflect a belief that this prosecution was initiated in bad faith. See Dkt.122 ¶5; see also Dkts.125-1, 125-2. Other information that has become public casts doubt on that claim and suggests the decision to dismiss the indictment was undertaken in bad faith. See, e.g., Dkts.150-3, 150-8. It is almost certainly beyond the judicial ken to definitively resolve that intramural dispute among executive branch prosecutors.

It’s not “beyond the judicial ken.” The rule exists because it is squarely within the judicial ken. No one wants a world where zombie prosecutions are maintained after prosecutors give up on them. Well, unless there’s the chance to kill someone that prosecutors have decided was innocent… then Clarence Thomas is right there to stand up for zombie prosecutions. But there’s a lot of daylight between judicial usurpation of prosecutorial power and recognizing that a dismissal is so corrupt that multiple attorneys quit in protest over it.

While Clement’s argument may be wrong, he is quite clever and has an interesting spin, arguing that the rule barring dismissals without leave of the court can basically only inure to the benefit of a defendant. Basically, the leave of court rule can only be for the purpose of protecting and not further jeopardizing the accused. This probably isn’t true, but it vibes well. And armed with this spin, Clement both agrees with the dismissal but disagrees on the subject of prejudice, concluding that Trump’s dismissal should be with prejudice to avoid… well, the whole thing Tom Homan talked about. This outcome, he notes, mirrors the clearly constitutional pardon power.

A dismissal with prejudice certainly protects the court’s interest in preventing coercive pretermit prosecutions. But you know what else does that? Going forward with the prosecution!

To be sure, an argument can be made—and has been made, see Dkts.128-1, 150-1—that the court can go further and effectively try to force the executive to maintain a prosecution it wishes to drop. But there are both practical and doctrinal problems with that extraordinary course. As a practical matter, even if the court were to deny the motion to dismiss, there is little the court could do to force the prosecutors to proceed with dispatch or stop them from dragging their feet and running out the speedy-trial clock. While a speedy-trial dismissal can be with or without prejudice, such delay at no fault of the defendant would likely produce a with-prejudice dismissal, but only after an unnecessary confrontation between the branches. That problem is particularly acute in a case like this, where the executive wants to drop the entire prosecution, not just specific defendants, cf. Nederlandsche, 428 F.Supp. at 116, and in circumstances, again like this, where the dismissal decision comes from the highest levels of the Justice Department, rather than reflecting an idiosyncratic decision by a line prosecutor.

The decision coming from the highest levels of the Justice Department probably should raise red flags instead of being cited as a justification but whatever.

While there may be circumstances where the inversion of the normal roles of the branches may be unavoidable…

Like maybe this case? If not, can we have some clarification of what case would be covered if “president uses DOJ to reward political cronies” isn’t that case? Sure, Trump can pardon Adams if he wants, but there’s value in keeping the pardon power distinct from the power to strangle prosecutions in the crib. Which Trump clearly understands which is why he wants to get rid of his newfound acolyte’s case this way instead of invoking a pardon.

… there are prudent reasons to avoid that in circumstances where a with prejudice dismissal eliminates any appearance that the executive is asserting undue influence over a public official and any incentive to seek dismissals for those purposes going forward.

Which assumes the faulty premise that “appearance of undue influence” was the only problem as opposed to upholding public integrity by shielding the DOJ from bad faith actors at “the highest levels of the Justice Department.”

But hey, he managed to square the circle of appeasing Trump while tempering the worst excesses so… congrats.

Full submission below.

Joe Patrice is a senior editor at Above the Law and co-host of Thinking Like A Lawyer. Feel free to email any tips, questions, or comments. Follow him on Twitter or Bluesky if you’re interested in law, politics, and a healthy dose of college sports news. Joe also serves as a Managing Director at RPN Executive Search.

Joe Patrice is a senior editor at Above the Law and co-host of Thinking Like A Lawyer. Feel free to email any tips, questions, or comments. Follow him on Twitter or Bluesky if you’re interested in law, politics, and a healthy dose of college sports news. Joe also serves as a Managing Director at RPN Executive Search.

The post Eric Adams Gets Helpful Assist From Paul Clement appeared first on Above the Law.