Save the Minerva Research Initiative — Again

Nicholas Evans in this op-ed explains the historic importance of the Minerva Research Initiative, and the implications of the initiative being shut down.

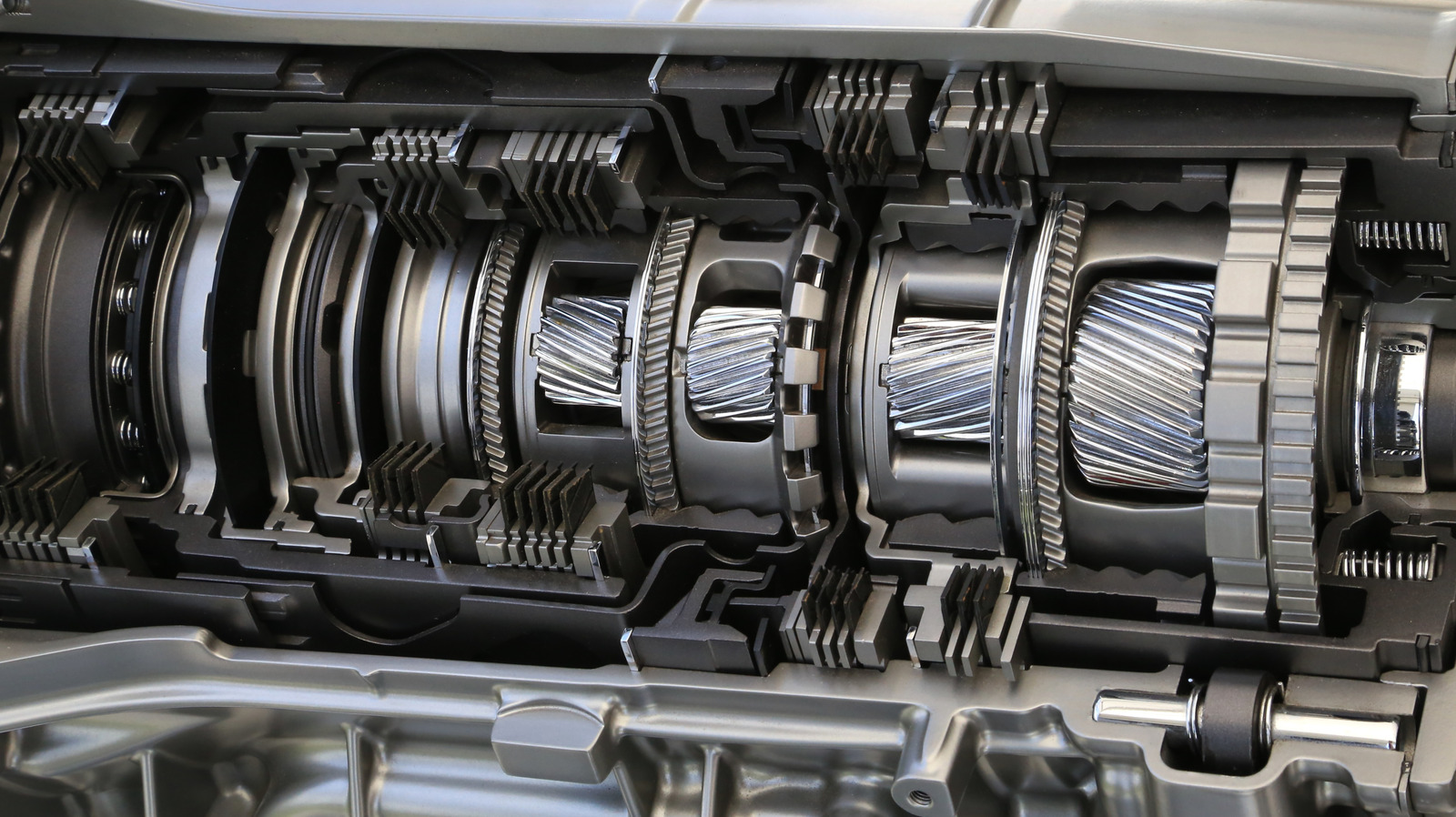

Pentagon grapples with growth of artificial intelligence. (Graphic by Breaking Defense, original brain graphic via Getty)

A free scientific enterprise promotes American health, wealth and security, but the rash of termination notices served to researchers around the country threatens this promise. At the Department of Defense, one of the first casualties of these attacks on science is the Minerva Research Initiative, a social sciences program built from the failures of 9/11, now shuttered in its entirety.

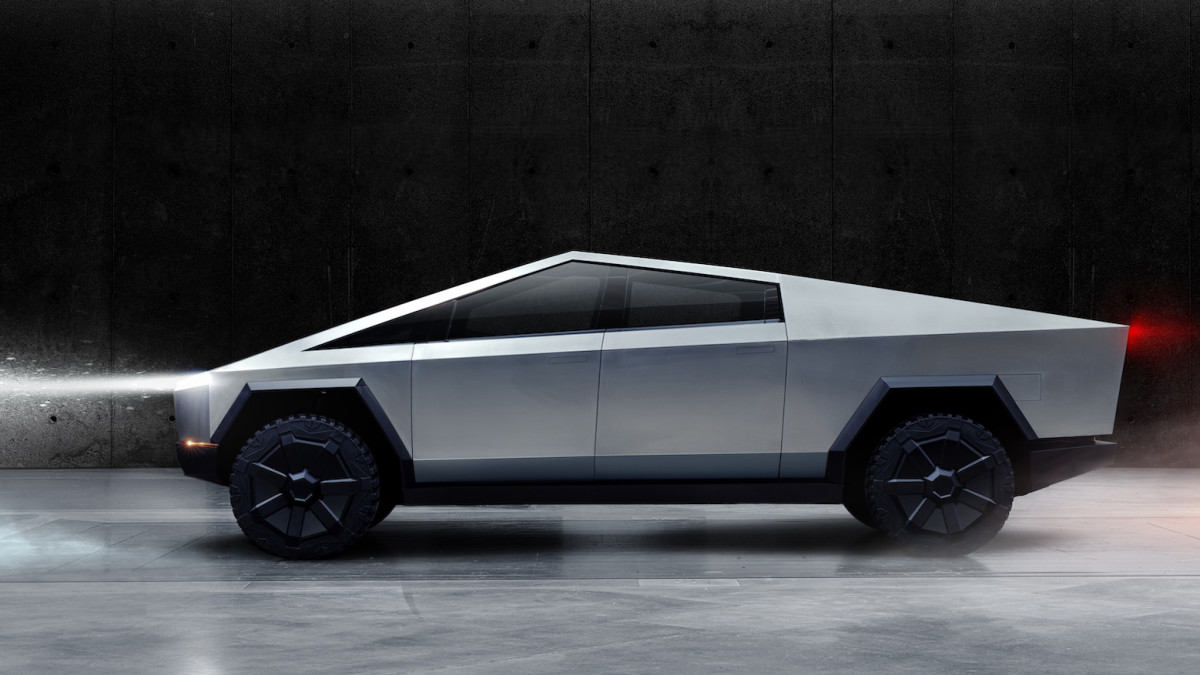

I’m one of the researchers affected. My team has had three projects terminated at the Department of Defense, including one on AI policy funded by the US Army. The DoD is the source of more than 80 percent of government funding for AI, and we study how predictions about the future of AI — from the utopian to the dystopian — influence defense policy, to ensure agency procurement and use of AI aligns with broader national security goals. At a time when AI development is notionally a top-tier effort for the military, we’ve been told this “no longer effectuates the program’s goals or agency priorities.”

There’s a larger story about the right to free inquiry being suppressed, given the tsunami of grant terminations that are killing American science. But for now, I just want to focus on DoD.

Minerva’s critical role comes from its history, with the recognition in 2001 that the US was unprepared for strategic surprises outside the scope of traditional armed conflict, and the subsequent understanding that social sciences research is not (yet) an off-the-shelf tool for defense contexts. In launching the program, then-Secretary Robert Gates claimed that “Too many mistakes have been made over the years because our government and military did not understand — or even seek to understand — the countries or cultures we were dealing with.” Minerva was designed to address the gap between operations and social science.

That gap wasn’t always there, and has its own history. Social sciences development was divorced from defense with the Mansfield Amendments of 1969 and 1973, which required basic scientific research funded by DoD to have a direct or apparent relation to military function. These changes shuffled much of the DoD’s scientific research back to the NSF, who without a comparable increase in budget simply couldn’t keep the required programs afloat. The strategic surprises and changing social landscapes in 2001 reversed this trend with the recognition that basic social sciences research had precisely that operational and strategic value but were underdeveloped. This resulted in the “6.1” — the basic research — turn to social sciences through Minerva.

Minerva has always been controversial, and the current secretary’s claim that DoD “does not do climate crap” — despite the DoD being keenly interested in the strategic impacts of climate change since 1990 — is a return to form. The program was almost shuttered in 2020 by an undersecretary of research and engineering who didn’t believe in the social sciences. Yet a 2020 National Academies review found Minerva researchers produce high quality, interdisciplinary, policy-forward results, and answer questions of critical interest to DoD and the wider national security community.

What the review recommended was a much better strategy for getting Minerva’s knowledge into the hands of those who would benefit from it, a common theme dating back to the breakdowns of the Human Terrain System. The last five years have been about just that: Minerva’s annual review occurs adjacent to the Pentagon and features personnel in an out of uniform; its researchers participate in DoD’s Basic Science Forum to ensure all commands are able to access our results; and Minerva investigators serve on a wide range of working groups and taskforces for everything from countering violent extremism to value alignment in lethal autonomous weapons. Minerva also runs the Defense Education and Civilian University Research (DECUR) community, which ties social sciences research directly into education and training for US professional military education institutions.

Closing Minerva goes against scientific and defense consensus on the role of social sciences in preparing the battlespace, the warfighter, and the country for emerging national security threats. It may violate the congressional authorization for these projects, written in as they are to individual service and DoD-wide budgets. And it makes the country less safe, sacrificing true national security for a vision of “lethality” that represents one of the least developed understandings of science and national security since the end of World War Two.

Minerva researchers predict and respond to terrorist activity on social media, study the role of critical mineral dependence on defense policy, define policy for creating super soldiers, and examine how warfighters can better interact with AI. We’re also one of the most cost-effective programs in DoD: Breaking Defense readers won’t be bamboozled by a $30 million dollar cut in the name of fiscal responsibility, when Pentagon cost overruns on single projects can cost tens of billions.

It’s time to save the Minerva program, again, and provide it with the stability it needs to contribute to America’s national security. Strategic surprises from old adversaries, new groups, new warfighting environments, and emerging technologies won’t stop coming. It is shortsighted for DoD to reduce its vision for national security in a way that fails to account for our complex and changing social environments and do so every five years. Reinstating Minerva and protecting it through congressional action against executive cuts will protect our troops, their folks back home, and the broader national security enterprise.

Dr. Nicholas G. Evans is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Philosophy at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, and a 2020-2023 Greenwall Foundation Faculty Scholar. He conducts research on the ethics of emerging technologies and national security, and on public health ethics and pandemic preparedness. His latest book, Gain of Function, was released in February of 2025.

.png)