Pentagon chiefs eye Ukraine’s surprise drone strike with anxiety – and envy

Service leaders worry about base defense, but Gen. David Allvin also asked, “Why don’t we think about including that in our Air Force and doing like the Ukrainians do?”

U.S. Soldiers with the Pennsylvania National Guard train with RQ-28 short range reconnaissance quadcopters during a field training exercise at Fort Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania, Oct. 19, 2024. (U.S. Army National Guard photo by Spc. Aliyah Vivier)

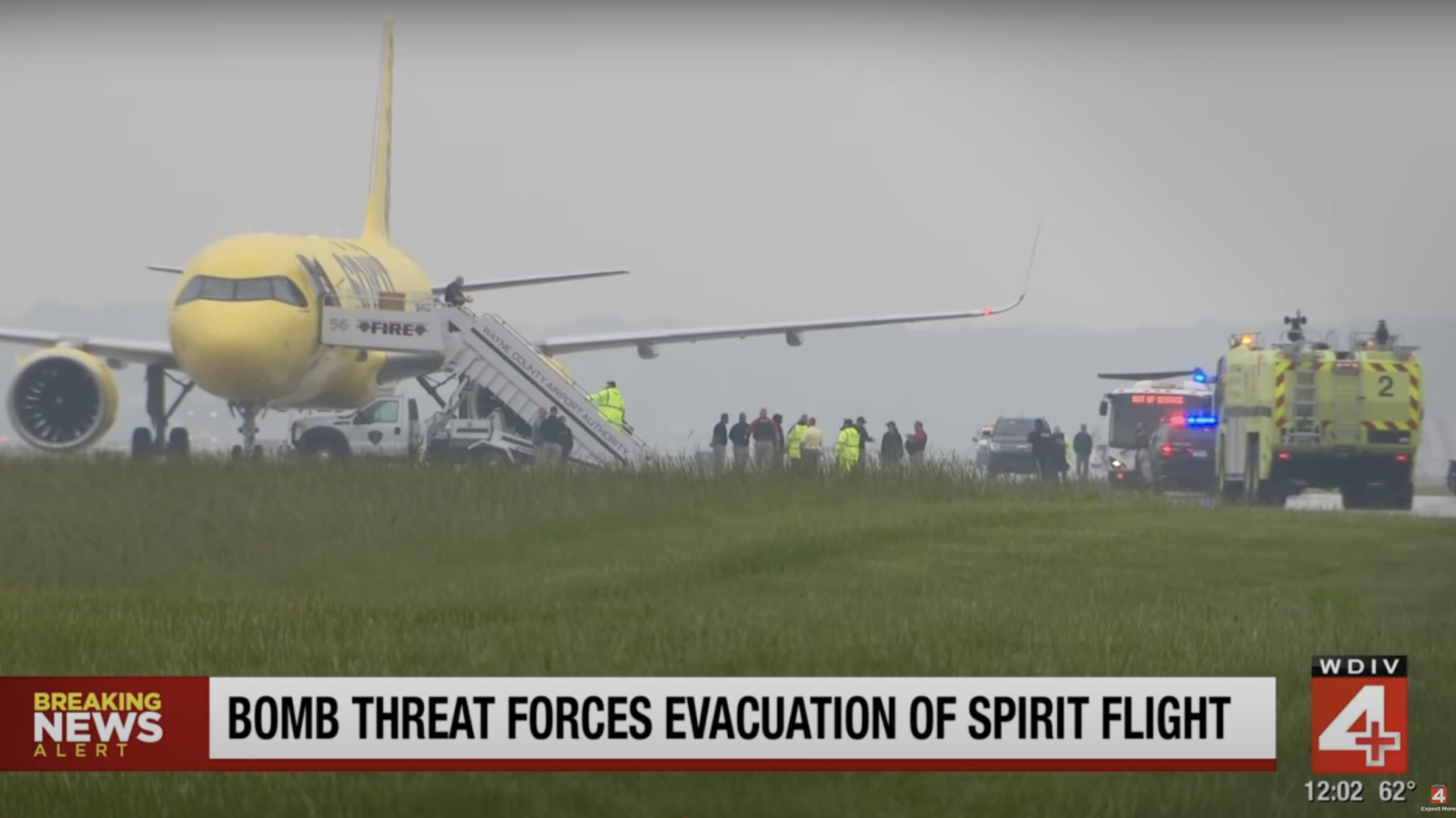

WASHINGTON — A day after cheap Ukrainian drones destroyed more than a dozen Russian heavy bombers and surveillance aircraft on the ground in an audacious surprise attack, senior American military leaders zeroed in on two key questions: are US defenses ready for that kind of attack, and could US offensive forces replicate it?

The intensity and innovation now on display in Ukraine go beyond anything “we even imagined” in the pre-war days, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David Allvin told the Special Competitive Studies Project’s AI+ Expo on Monday: “That’s one thing that should humble us.”

So, in the aftermath of Ukraine’s “Operation Spider Web” drone strikes this weekend, “we might look at that and think, ‘Wow, what would we do if we were attacked, you know, by a country that’s doing what Ukraine did, [in] what we thought was an impenetrable defense?” Allvin said. “That’s a natural reaction.”

Even the way the news broke Sunday shows how transparent, even exposed, once-hidden military infrastructures have become. Smartphone videos and social media posts reported the Ukrainian offensive almost immediately, and independent open-source intelligence analysts moved swiftly to confirm and double-check the damage reports using the kind of satellite imagery once exclusive to government spy agencies.

“We all knew about that within a matter of minutes. Everything was out there on open source,” said Gen. Randy George, the Army Chief of Staff, speaking at the same SCSP conference as Allvin.

RELATED: Zelenskyy’s drone card: How Operation Spiderweb impacts Russia’s capabilities going forward

That transparency reinforces a lesson of the modern hyper-connected, pervasively surveilled world that the Army has been wrestling with for years, George said.

“You can’t really hide anymore,” he told the conference. “On the modern battlefield, you’re going to have to be dispersed, lower signature, all of those things — which, you know, we talk a lot about with our with our troops and with our commanders.”

In his talk, Allvin echoed those remarks. “It just shows that the old way of thinking, that there are sanctuaries, and there are places that you have to fight your way into from increasing distances, is sort of going away,” he said.

In another speech on Tuesday, Allvin said that the Ukraine attack, while “eyebrow-raising,” wasn’t a wake-up call only in that the US has been “awake” to the problem for a while now.

“We’ve always known that hardening our bases is something that we need to do, and so we have that, actually, in our budgets, to be able to get more resilient basing, and we have some hardening for the shelters, and we have some some more survivable capabilities of our bases,” he said at an event put on the Center for a New American Security. “Right now, I don’t think it’s where we need to be.”

The Army also plays a leading role in defense against air attack, including rising investments in jammers, lasers, high-powered microwaves, and good old-fashioned anti-aircraft machineguns optimized to take down small, slow, nimble drones. But it has acknowledged in the past just how difficult it is to defend a facility from a myriad of threats at the same time.

On the tactical level, George said at the SCSP event, “we’re just getting ready to kick off a big exercise right now called Fly Trap, this month and the next, to make sure that we’re focused on how we can counter drones inside of our formation.” Strategically, the Army is also a part of the Trump Administration’s high-profile Golden Dome initiative, he added, although that “is going to be a joint mission – we’re working with all the services on this.”

For George’s civilian boss, Army Secretary Daniel Driscoll, “It is probably the challenge of our lifetime to figure out how to protect ourselves.”

Going On The Drone Offensive

But while the service chiefs fretted about US defenses, they also saw opportunity on the offensive.

“Here’s what I think about it: Why don’t we think about including that in our Air Force and doing like the Ukrainians do?” Allvin said at the SCSP event. “When we say ‘airpower, anytime, anywhere,’ it doesn’t have to be the most exquisite, exclusive, expensive, sophisticated platform. It just needs to be able to generate effects … [and] you can create a lot of disruptive effects.”

That doesn’t mean Allvin wants to stop buying high-end platforms: “We need that, because we always need to be able to penetrate [defended airspace] and have air dominance,” he emphasized. But, he said, “not every part of our Air Force has to be the high [end], air-dominance, exquisite” systems.

RELATED: Air Force officer sees options for ‘cheaper,’ less ‘exquisite’ CCA drone wingmen

Likewise George said the Army wants more and cheaper drones (it just cancelled the long-awaited but large Future Tactical UAS), but raised another issue: right now so many are built in China.

“What we’re going to have to figure out is, I think, right now, the Chinese have a big part of the market for drones,” he said. “One of the things that we’ve spent a lot of time talking about is… how does the US Army become the drone manufacturer, working with private industry?”

By manufacturing, George and other defense reformers don’t just mean mass production of a few static designs, but also mass innovation. Ukrainian drone-makers not only turn out large numbers of UAVs, but rapidly adapt their designs to a changing battlefield where a given tactic or technology may go from dominant to obsolescent within weeks.

The Pentagon bureaucracy wasn’t built to update equipment at this pace, an oft-cited concern of military officials in industry alike that relatively recent initiatives like the Replicator program have struggled to address.

“Yesterday was a really good example of just how quickly technology is changing the battlefield,” George said. In Washington, “everybody talks about POM cycles” — the five-year Program Objective Memorandum process — “and everybody talks about the program of record. And I think that’s just old thinking.”

“The technology is changing in our pocket,” George said. “We’re going to have to adapt all of our processes. … So we’re going to need a lot more agility in how we buy things. And again, as the Secretary said, that’s a struggle, because everybody wants us to buy the same drone for the next 25 years.”

The services can’t “lock in” to any specific tech on such long timelines anymore, Allvin agreed.

“We need to be careful that when we make our large capital investments, we don’t do it in a way to where we are locked in,” he said. “We need to be able to build them to where they’re adaptable to [new] mission systems, can ingest disruptive technology and produce a new level of dominance. And that speed happens so fast. We need to make sure that our bureaucratic processes and our imagination and our overall institutional agility is sufficient to be able to bring on those technologies.”

It’s the institution, not the individuals, that’s struggling to adapt to new tech at speed, Allvin added. “The institution is having a problem,” he said. “The airmen are not. The airmen are just fantastic. And so the challenge is to be able to harness that individual talent.”

“There’s this scrappiness and innovation of the American soldier,” echoed Driscoll. “They’re just the most remarkable, talented people we as a nation, in my opinion, have.”

Michael Marrow contributed to this report.