IVD Intended Purpose: Why it matters more than ever under IVDR

Under IVDR, clear and specific IVD intended use criteria are required and introduce significant challenges for manufacturers seeking CE Marking and global market access. With updated compliance deadlines approaching, how can manufacturers manage risk and avoid regulatory delays and disruptions in their market strategies? The post IVD Intended Purpose: Why it matters more than ever under IVDR appeared first on MedTech Intelligence.

For IVD manufacturers, the intended purpose has always been a fundamental aspect of a medical device, defining its claims and use within a specific clinical environment. However, under the EU’s In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation (IVDR), this definition now carries even greater regulatory weight. IVDR mandates unprecedented precision in how manufacturers articulate intended purpose, influencing everything from device classification and risk management to clinical evaluation and market approval.

The transition from the IVD Directive (IVDD) to IVDR marks a fundamental shift in regulatory expectations. Manufacturers can no longer rely on broadly defined intended purposes; instead, IVDR requires clear, specific criteria that define how a test is used, for whom, in what clinical context, and with what limitations. The European Commission’s official guidance reinforces this shift, emphasizing the introduction of a risk-based classification system and stricter requirements for clinical evidence.

While these changes enhance patient safety and transparency, they also introduce significant challenges for manufacturers seeking CE Marking and global market access. With IVDR compliance deadlines approaching, manufacturers that do not act now risk falling behind competitors, facing regulatory delays, and disrupting their market strategy.

Why has IVDR reinforced intended purpose requirements?

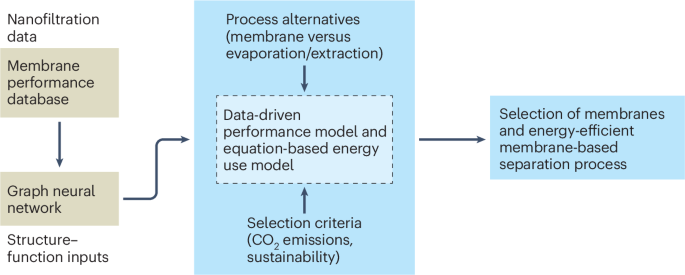

The IVDR introduces two fundamental changes that directly impact manufacturers. First, it replaces the previous list-based classification approach with a risk-based classification system that aligns with international regulatory standards. This system divides IVDs into four classes, ranging from low-risk (Class A) to high-risk (Class D), ensuring that regulatory oversight is proportionate to patient risk. Second, IVDR emphasizes the importance of clinical evidence, requiring manufacturers to move beyond analytical validation and demonstrate how their devices perform in real-world clinical settings.

Unlike IVDD, where an IVD’s classification depended largely on the analyte it measured, IVDR now considers the broader clinical use scenario, the target population, and how the device is integrated with other technologies. This shift, outlined in Annex I, 20.4.1(c), requires manufacturers to define precisely how their test is used, the specific patient group it serves, and whether it is intended for diagnosis, screening, or monitoring. These changes significantly impact regulatory pathways, making the classification process more rigorous and requiring stronger justification from manufacturers.

How this impacts IVD manufacturers

For the first time, IVD manufacturers must explicitly define their intended purpose claims in alignment with IVDR’s new standards. Under IVDD, intended purpose statements were often broad and analytical in nature. A typical claim might have stated that an IVD test was intended to measure a specific parameter in human plasma and was for professional use only. Under IVDR, however, the same test must now include details on how it is performed—whether it is an automated or manual process—the type of sample it uses, the specific age group and condition it targets, and whether it is intended for screening, diagnosis, or another clinical application.

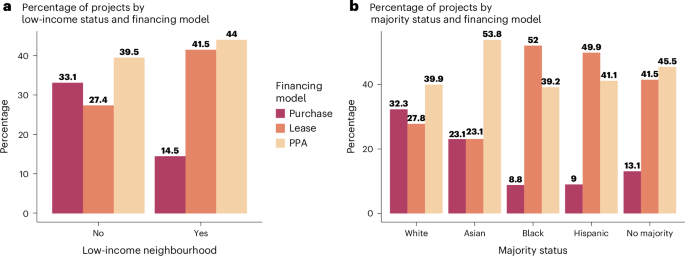

This shift limits the flexibility manufacturers once had. With IVDR’s stricter requirements, clinicians must now adhere strictly to the stated intended purpose. If a laboratory uses the test outside the manufacturer’s defined claims, it would be considered off-label use, requiring additional validation by the laboratory. This restriction is particularly challenging for sales-driven manufacturers, as it may limit how their devices are marketed and adopted in clinical practice. As a result, many legacy IVD devices that have passed the Notified Body (NB) process and are eligible for marketing under IVDR are still being marketed under IVDD.

Beyond regulatory adjustments, these changes present significant operational and financial challenges, particularly for small and mid-sized manufacturers that may lack the resources to efficiently manage the transition. Unlike larger corporations with dedicated regulatory teams, smaller companies must navigate the complexities of compliance while balancing costs associated with compiling clinical evidence, updating risk assessments, and ensuring documentation consistency.

How regulatory authorities use intended purpose to classify IVDs under IVDR

The intended purpose is not just a description of the device—it is the foundation for classification under IVDR, impacting everything from risk assessment to the conformity assessment process. A reagent that is part of an automated system, for example, may trigger additional regulatory scrutiny, requiring a review of the corresponding instrument and software. Similarly, a Companion Diagnostic IVD would necessitate coordination with national agencies or the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to ensure alignment with therapeutic product approvals.

For high-risk IVDs, particularly those in Class D, the involvement of European Reference Laboratories (EURLs) is required to verify the device’s performance and reliability. Before a Notified Body can begin the Technical Documentation Assessment (TDA), it must first validate the manufacturer’s intended purpose statement against the eight criteria outlined in Annex I, 20.4.1(c). If the information provided is unclear or inconsistent, the manufacturer may be required to revise not only the intended purpose statement but also related documents, such as performance evaluation reports and risk assessments. In some cases, manufacturers may need to conduct additional clinical studies, delaying the CE Marking process and market entry.

The business risks of an inadequate intended purpose

Failing to define a clear, IVDR-compliant intended purpose can create significant business risks. One of the most immediate consequences is the impact on technical documentation. If the intended purpose does not align with IVDR’s detailed requirements, manufacturers may need to revise multiple documents, including risk management files, clinical evidence reports, and instructions for use. These revisions can be time-consuming and costly, particularly for companies with large product portfolios transitioning from IVDD to IVDR.

Beyond documentation challenges, failing to meet IVDR’s intended purpose requirements can lead to delays in the Notified Body review timelines. Under EU Regulation 2024/1860, there is a 2.5-year review period for legacy devices, and if an intended purpose statement is deemed inadequate, a Notified Body may reject an application or place it at the back of the queue for review. Given the high demand for Notified Body services under IVDR, such delays could push some manufacturers past regulatory deadlines, preventing them from legally marketing their devices in the EU.

The risks extend beyond the EU market. Many countries recognize CE Marking as a prerequisite for registration, and if an IVD does not achieve timely CE Marking, it may also face regulatory roadblocks in non-EU markets. This could disrupt global commercialization strategies, forcing companies to invest additional resources into alternative regulatory pathways or risk losing market share.

IVDR compliance is a strategic imperative

The transition from IVDD to IVDR is more than just a regulatory shift—it fundamentally changes how IVD manufacturers define and position their products. Intended purpose now plays a central role in compliance, directly influencing classification, risk management, clinical validation, and a product’s ability to secure CE Marking and enter the EU market. With stricter regulatory scrutiny, vague or broadly defined intended purposes are no longer viable. Every detail must be precise, justified, and aligned with IVDR requirements.

At the same time, this shift presents an opportunity. Manufacturers that take a proactive approach to compliance can turn IVDR’s stricter framework into a competitive advantage. A well-defined intended purpose not only accelerates approvals but also strengthens credibility with regulators and healthcare providers. Ultimately, those who adapt early will be better positioned than competitors still navigating compliance challenges, ensuring greater stability in a changing regulatory landscape.

The post IVD Intended Purpose: Why it matters more than ever under IVDR appeared first on MedTech Intelligence.