‘If Russia is coming, then we will bring the war to Russia’: Inside NATO’s muscular new deterrence plans

Europe and the United States are more aligned than some headlines suggest—but they have different perceptions of the threat.

Russian President Vladimir Putin increasingly perceives Europe to be weaker than it is, they say, while the White House fails to grasp the severity of the Russian threat.

At the NATO summit later this month, members will discuss not only increased defense budgets, but also new operational concepts to respond immediately to a Russian attack—including counterstrikes inside Russia—Estonian Foreign Minister Margus Tsahkna told Defense One at the GLOBSEC security conference.

“The new concept is that if Russia is coming, then we will bring the war to Russia. That's what we are talking about,” Tsahkna said. “We have no time then to discuss whether we can use one of the other weapons or whatever. We have no time. We need to act within the first minutes and hours.”

That new doctrine builds on the regional defense plans NATO adopted at its 2023 summit, which centralized more authority under U.S. Gen. Christopher Cavoli, NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander Europe, to respond rapidly— in coordination with Eastern European members—in the event of a Russian assault.

However, this year’s summit will go further. It is expected to outline the specific capabilities Europe must field to be ready for conflict with Russia the day of an attack. “Now we have [capability targets] for this concept,” Tsahkna said.

The upcoming summit is intended to accelerate the alliance’s readiness, said NATO official speaking on background. “We don't have 19 years to wait. No. Be ready to go now,” the official said. “And it's not because the U.S. might be withdrawing forces or not committing forces or anything like that. It’s just, we need to be ready to go.”

A senior European military official added that urgency is critical, noting, “We all agree that we need to strengthen the deterrence, because Russia may try something to test our Article 5 in three to five years. It takes six years to build a building in our [Ministry of Defense].”

Gen. Karel Řehka, the Czech Republic’s military chief, said the new capability targets represent a significant departure from earlier plans, which often amounted to vague commitments. “They are really driven by threat. Not only threat, also innovation—but mostly by threat,” he said.

NATO members have provisionally aligned on sweeping new capability targets and are expected to formally adopt national spending goals of 3.5% of gross domestic product on so-called “core” defense development.

“These capabilities, encompassing air defense, combat aircraft, tanks, drones, personnel, and logistics, among others, will keep our deterrence and defense strong and our one billion people safe,” NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte said during a June 5 press conference.

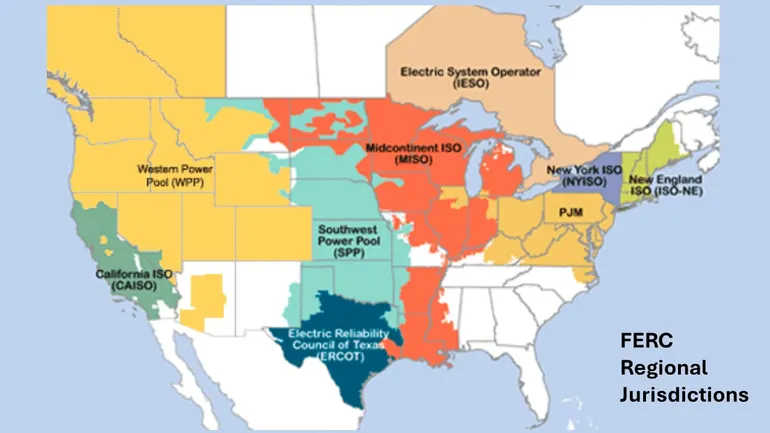

At the summit, members are also expected to agree to an additional 1.5% annual investment in infrastructure such as roads, electricity, and industry. NATO officials also told Defense One that development of space-based capabilities will be a priority.

Washington and Europe: aligned, but not fully

The 3.5% spending goal is widely viewed as a win for former President Donald Trump, who called for a similar increase on the campaign trail—a demand that drew quick support from a NATO official during last year’s GLOBSEC summit.

Throughout the forum, however, European leaders repeatedly emphasized that while they seek to grow their own defense industries, they do not want to cut ties with the United States or American defense firms, which continue to supply arms and intelligence vital not only to Ukraine’s war effort, but to Europe’s own security.

Still, concerns persist that U.S. commitment to NATO’s collective defense could shift under Trump. His past remarks—combined with reports that the White House has considered withdrawing troops from Europe or pulling back the U.S. nuclear umbrella—have sparked conversations in European capitals about relying more on France’s smaller nuclear arsenal for deterrence.

But Jim Stokes, director of nuclear policy at NATO, dismissed those fears during a panel at GLOBSEC.

“The United States has been extremely clear that there is nothing changing with regard to its nuclear deterrence and its commitment,” he said. “That includes its posture within Europe. It includes its commitment to the allies, and it’s also about the commitment of our European allies and Canada.”

A NATO official, speaking on background, echoed that message, but added that the White House contributed to the confusion. “The internal messaging is [now] very good. It’s gotten better. We’ve talked with them about what they’re saying. Now, they are very clear: we’re not gonna change anything on the nuclear side,” the official said.

A March misstep and lingering doubts

Defense, military, and industry officials also said they do not expect a repeat of the incident in March in which the United States briefly paused the sharing of intelligence with Ukraine—including commercial satellite imagery and data from U.S. companies—and prevented European allies from purchasing and passing that intelligence to Kyiv.

But one senior European defense official said the move significantly damaged trust and dampened European enthusiasm to buy American weapons or data services. “There’s a question of trust, yeah? Whether we buy or not we buy from the United States. Can we use these systems? Can we use the jet fighters? This is the main, main concern,” the official said.

That said, the official acknowledged that “the new approach from the White House on that subject is getting better and better.”

A common understanding is beginning to emerge: NATO must invest more heavily in its own defense; the United States will maintain its nuclear deterrence presence in Europe; and U.S. defense and intelligence firms will continue to contribute—though increasingly at European taxpayer expense rather than through the U.S. defense budget.

Yet differences in worldview remain, said Brian Finlay, president and CEO of the Stimson Center, speaking at GLOBSEC. Finlay said he has been in regular contact with White House officials. “The respective threat assessments here in Europe versus back in Washington are further apart than they have been at any time, perhaps since the end of the Cold War.”

Putin, meanwhile, may be making a dangerous error built on similarly flawed perceptions, Řehka warned. “I think we are coming to the most dangerous situation since the end of the Cold War, and that’s Russia believing that Europe is weak. That’s really, really dangerous. It’s not true. But if Russia starts to believe that, then it increases the potential for miscalculation.”

And if Russia acts on that belief, it will pay a price, the senior European defense official said.

“If we can fulfill our plans, the price for Russia will be pretty high [should it test NATO in a formal invasion or via some less-obvious attack]. But the turning point is actually what is going to happen with Ukraine, because [Putin’s] stuck there. The narrative that Russia is going to win very soon, it’s not correct.” ]]>

![Israel drama and good news for the F-35: Paris Air Show Day 1 [Video]](https://breakingdefense.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2025/06/IMG_1805-scaled-e1750092662883.jpg?#)

![[Updated] Sudden Deployment of Dozens of U.S. Air Force Tankers Raises Questions](https://theaviationist.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Stratotanker100Years_2-e1750080240327.jpg)