Army chief mulls Project Convergence’s future, with industry mixed on event’s value

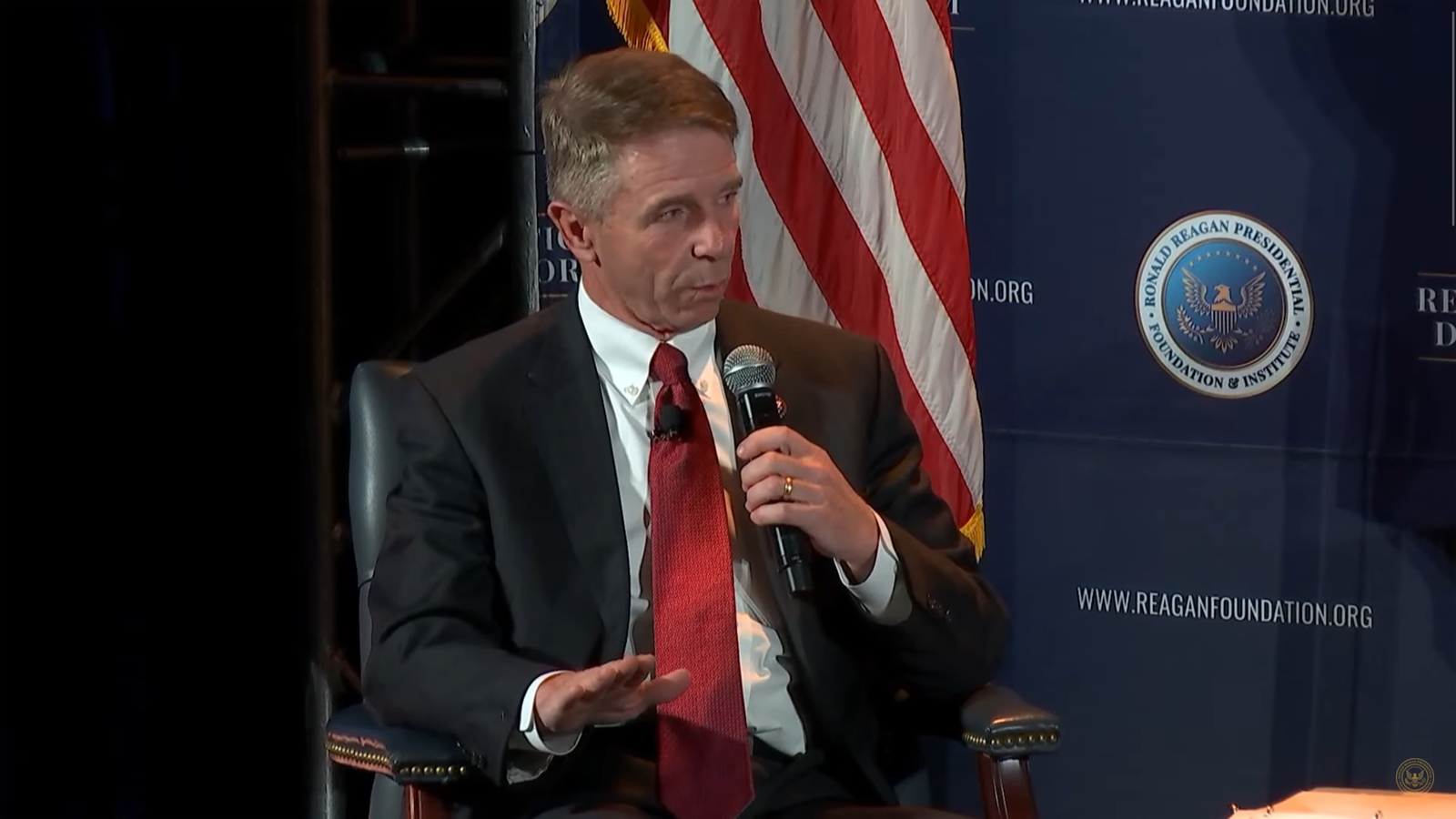

“This was a really, really worthwhile experiment out here. … What we don’t want to do is just continue to do something just because we want to continue to do it,” Gen. Randy George told Breaking Defense.

An SMET Increment 1 outfitted with quadcopters was used in a demo at Project Convergence Capstone 5 earlier this month. (Ashley Roque/ Breaking Defense)

FORT IRWIN — Army Chief of Staff Gen. Randy George is weighing the future of Project Convergence, the service’s premiere event designed to experiment with new technology and weapons, as some inside industry are questioning whether the exercise still retains value.

“We [have] to constantly look at everything that we’re doing,” the four-star general told Breaking Defense when asked about the investment of time and money to host the multi-week capstone event. “We are having discussions about… how do we move forward.”

George, who was vising Ft. Irwin to check out the latest iteration of Project Convergence, later added, “What we don’t want to do is just continue to do something just because we want to continue to do it. If it’s not going to be a maximum value, then we have to look at it.”

The Army Futures Command (AFC) was just over two years old in summer 2020 when the first Trump administration hosted the inaugural Project Convergence event at Yuma Proving Ground in Arizona. It was billed as the service’s contribution to the Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control (CJADC2) effort and a venue for industry to show soldiers and service leaders what their weapons can do. In turn, the service had space to experiment with new tech and operational concepts in a live-fire and simulated environment.

Project Convergence has mushroomed in the intervening years to include work with sister services and foreign partners. The AFC also sought to reframe it as an ongoing experimentation series that leads up to the higher-profile capstone event. Now in its fifth iteration, or PCC5, this year’s ongoing capstone event is being held at both the National Training Center at Ft. Irwin, Calif. and across the Indo-Pacific to include Hawaii, Guam, Japan, the Philippines, Australia, and French Tahiti. (The Army did not respond to questions about the cost of this year’s capstone event.)

From his vantage point, George said this year’s focus on the network and plans for the Next Generation C2 (NGC2) justified the event.

“This was a really, really worthwhile experiment out here, from what I saw,” he said in California. “Whether it was network, what we did for loitering munitions… what we did on the space triad… long-range fires, everything that I saw there, I think is worthwhile.”

But a variety of factors could weigh into the event’s fate including other experimental initiatives and its fruitfulness.

For example, last year George launched forward with “Transformation in Contact.” TiC, as it is known, is designed to get capabilities into the hands of soldiers at a faster clip and have them working with it in real world conditions and training rotations.

In theory, TiC is supposed to home in on nearer-term capabilities while Project Convergence looks “a little bit further out,” AFC head Gen. James Rainey told an audience at the McAleese defense programs conference March 18. However, that isn’t always the case, which can cause confusion.

“We just finished up out at NTC [for Project Convergence]. About half the stuff out there is ready to go,” Rainey said. “Companies aren’t bringing us things and saying, ‘We like this. We can have it to you in two years. Companies are coming and saying, ‘We have this right now. If you want it, you can have it.’”

Ironing out overlapping experimentation avenues could be part of the calculus in deciding if and how to proceed with Project Convergence, especially in the new Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) era.

It doesn’t help that after five years of Project Convergence, reaction inside industry remains mixed on a core question: What are the tangible benefits of taking part in the exercise? Convergence.

Sand and wind

Out in the desert sands at Ft. Irwin this year, PCC5 centered enabling operations at the corps level and below with four focus areas — command and control, ground-based maneuver, cross-domain fires and formation- based layered protection. (In April, the Indo-Pacific scenario will take place at the combatant command level with all service components.)

While there were larger weapons in the desert sands including the Army’s Autonomous Multi-domain Launcher (AML) and one produced by a Raytheon-team, the bulk of the tech focused on smaller ground and aerial drones.

On the ground, those ranged from autonomous versions of General Dynamics Land Systems Small Multipurpose Equipment Transport (SMET) robotic mules with various payloads, to a prototype of a Medium Multipurpose Equipment Transport (MMET) by a team that includes Plasan and Forterra. (The Army is expected to launch a MMET competition later this year.)

Up in the air, soldiers and industry used a variety of weapons ranging from small quadcopters to launched effects to two cargo aerial drones — a Multi-Mission Expedition (MULE) from WaveAerospace designed to ferry up to 100 lbs, and Phenix Ultra’s 2XL Heavy-Lift UAS designed to carry up to 1,000 lbs.

Of the 153 pieces of tech and weapons used, “generally speaking, it’s fair to say that most of the capabilities we have… are around the idea of attritable,” Brig. Gen. Zachary Miller, commander of Joint Modernization Command, said during an interview.

While Miller and other Army officials heading up PCC5 may have a clear fix on the goals for the capstone event, several industry officials attending said the aims were not always communicated down the chain.

“Frankly, that actually needs some DOGE,” one quipped when posed that question.

A second industry source said that it was only after a week in the desert watching an abundance of smaller ground robots and UAS swarms steam by that he concluded that this year’s focus was on dismounted troops.

“I sat out in the desert for three days and saw lots of ‘stuff’ drive by… I started putting three and six together and rounded up to 10,” that industry source added.

However, two other industry sources from different companies separately said they left Ft. Irwin after having a positive experience with sufficient communication from the service.

“The Army has their own goals, and they’re shared with industry,” the third source said.

“It’s just adding more and more capability as the years go… [and] from my perspective, personally, it was a very positive experience. I think we’re seeing real progress made and working out how robots fit into the manned formation.”

Progress with how tech fits inside formations does not equate to material solutions actually emerging from the experiment, a point several sources raised and the Army did not directly respond to.

That first industry source, for example, said it remains unclear how the Army is using this experiment and others to inform decisions and more transparency is critical.

But a fifth industry source cautioned against simply abandoning Project Convergence and instead offered up some potential improvements.

“It has not transitioned items in the five years it has been around, but let’s not throw the baby out with the bath water,” that industry source said. The venue, he added, has provided companies with an avenue for directly working with soldiers in an operational setting and engaging with senior service leaders. What could potentially make it more valuable to industry, though, are better avenues for scaling and requirement validation.

“The fact that there are not requirements writers embedded at every point means that there is maybe too much flash going on,” that source said. “We had requirements folks with us at about 50 percent of the tech demonstrators.”