The shape of things to come: the next generation of car designers

Designer Callum (left) and Riversimple boss Spowers cast a keen eye over every model Coventry Uni students competed to design a radical FCEV supercar that Riversimple will put into production by 2030 Pity the emerging generation of car designers. They grow up obsessed like the rest of us, but with the usual desire to drive and own cars overlaid by a burning need to create inspirational designs of their own. When these budding Giugiaros get to university, they put three or four years into learning how to create unique vehicles, yet many will graduate without ever working on a real, live project. For competitive reasons, car companies keep their plans secret, even from future employees. Which is one vital reason why a new cooperative project between Riversimple, the Wales-based builder of zero-emissions hydrogen fuel cell cars, and a 14-strong group of students at Coventry University’s Transport Design school – to propose a new production car – is so special. Riversimple, which already makes its unique Rasa lightweight urban two-seater for subscribers who will never own them, operates so far away from current motor industry norms that it doesn’t have formal competitors. Secrecy is less of a problem; publicity is oxygen. Soon, there’s going to be a brand-new Riversimple supercar, the flagship of a new generation of more mainstream hydrogen models from this progressive but idiosyncratic manufacturer. The mantra of its founder, former motorsport engineer and historic car restorer Hugo Spowers, is “to pursue, systematically, the elimination of the environmental impact of personal transport”, hence his concentration on hydrogen power, whose only by-product from driving is pure water. If things go right, the new Riversimple generation will be launched later this decade with a light, beautiful and ultra-low-volume supercar as its flagship. In a design competition set up by Spowers and the Coventry design school’s assistant professor, Aamer Mahmud, who is an accomplished former car designer, the university’s latest cohort of postgrad Transport Design students are taking the first steps to make this sophisticated and very special two-seat coupé a reality. For the students, this is a unique exercise: they’re creating a car that must conform with today’s laws on visibility, lighting and crash safety, with plausible cabin access and practical 17in wheel/tyre dimensions, not the huge hoops with ribbon-like rubber that adorn most design proposals. Spowers, who designed single-seat racing cars in his former career, strongly disapproves of the direction of current hypercar design, seeing it as an “arms race” driven by the mass and size of the huge engines or huge batteries needed to propel gargantuan cars with unfeasibly high performance. The resulting machines may be very fast, he says, but they’re “uncomfortable and unwieldy rather than fun”. Spowers envisages a Riversimple supercar similar in headline dimensions to Ferrari’s Dino 246 GT – which means around 4200mm long and about 1700mm wide. The new car’s wheelbase will be 2300mm, and its roof height will be a little lower than the Dino’s at 1100mm. Spowers’ supercar will have a mechanical layout like no other, with the powertrain distributed rather than being front- or rear-engined. It will be driven by four inboard electric motors (one per wheel). Electric power will come from a front-mounted hydrogen fuel cell and be stored in a rear-mounted 45kg array of supercapacitors (rather than a 500kg bank of heavyweight cells as used in a conventional battery-electric car). The hydrogen tank, enough for a 400-mile range, will be sited behind the seats. Because of the unique powertrain and the lightweight construction it allows, the car will weigh just 620kg at the kerb instead of the 1400-1800kg of a battery alternative, which is why Spowers has dubbed his new enterprise as ‘Project Chapman’, invoking the name of the legendary Lotus founder who loved lightness and compactness above all. The unique characteristics of fuel cell power give the car an extraordinary performance envelope – true supercar acceleration (0-100mph in just 6.4sec) but a top speed of just 100mph. “The top speed isn’t ‘capped’,” explains Spowers. “It’s simply what the car can achieve with the size of fuel cell we’ve chosen. We think it’s enough. "To go faster, we could fit a bigger fuel cell, which would lead to a bigger fuel tank, a larger and heavier structure, bigger motors and brakes, more supercapacitors: a whole weight-gain cycle would begin and the dynamic attributes that really matter would be compromised. "In the design we have, the fuel cell is sized for a constant 100mph top speed, but that’s all there is.” Spowers’ styling recipe is exacting. He wants his car to be modern and arrestingly beautiful in a timeless sense, avoiding the aggressive, “monsterish” look of current hypercars. Its sophistication needs to help justify a high cost, well into hundreds of thousands. It must be a low sup

Designer Callum (left) and Riversimple boss Spowers cast a keen eye over every modelCoventry Uni students competed to design a radical FCEV supercar that Riversimple will put into production by 2030

Pity the emerging generation of car designers. They grow up obsessed like the rest of us, but with the usual desire to drive and own cars overlaid by a burning need to create inspirational designs of their own.

When these budding Giugiaros get to university, they put three or four years into learning how to create unique vehicles, yet many will graduate without ever working on a real, live project. For competitive reasons, car companies keep their plans secret, even from future employees.

Which is one vital reason why a new cooperative project between Riversimple, the Wales-based builder of zero-emissions hydrogen fuel cell cars, and a 14-strong group of students at Coventry University’s Transport Design school – to propose a new production car – is so special.

Riversimple, which already makes its unique Rasa lightweight urban two-seater for subscribers who will never own them, operates so far away from current motor industry norms that it doesn’t have formal competitors. Secrecy is less of a problem; publicity is oxygen.

Soon, there’s going to be a brand-new Riversimple supercar, the flagship of a new generation of more mainstream hydrogen models from this progressive but idiosyncratic manufacturer.

The mantra of its founder, former motorsport engineer and historic car restorer Hugo Spowers, is “to pursue, systematically, the elimination of the environmental impact of personal transport”, hence his concentration on hydrogen power, whose only by-product from driving is pure water.

If things go right, the new Riversimple generation will be launched later this decade with a light, beautiful and ultra-low-volume supercar as its flagship.

In a design competition set up by Spowers and the Coventry design school’s assistant professor, Aamer Mahmud, who is an accomplished former car designer, the university’s latest cohort of postgrad Transport Design students are taking the first steps to make this sophisticated and very special two-seat coupé a reality.

For the students, this is a unique exercise: they’re creating a car that must conform with today’s laws on visibility, lighting and crash safety, with plausible cabin access and practical 17in wheel/tyre dimensions, not the huge hoops with ribbon-like rubber that adorn most design proposals.

Spowers, who designed single-seat racing cars in his former career, strongly disapproves of the direction of current hypercar design, seeing it as an “arms race” driven by the mass and size of the huge engines or huge batteries needed to propel gargantuan cars with unfeasibly high performance. The resulting machines may be very fast, he says, but they’re “uncomfortable and unwieldy rather than fun”.

Spowers envisages a Riversimple supercar similar in headline dimensions to Ferrari’s Dino 246 GT – which means around 4200mm long and about 1700mm wide. The new car’s wheelbase will be 2300mm, and its roof height will be a little lower than the Dino’s at 1100mm.

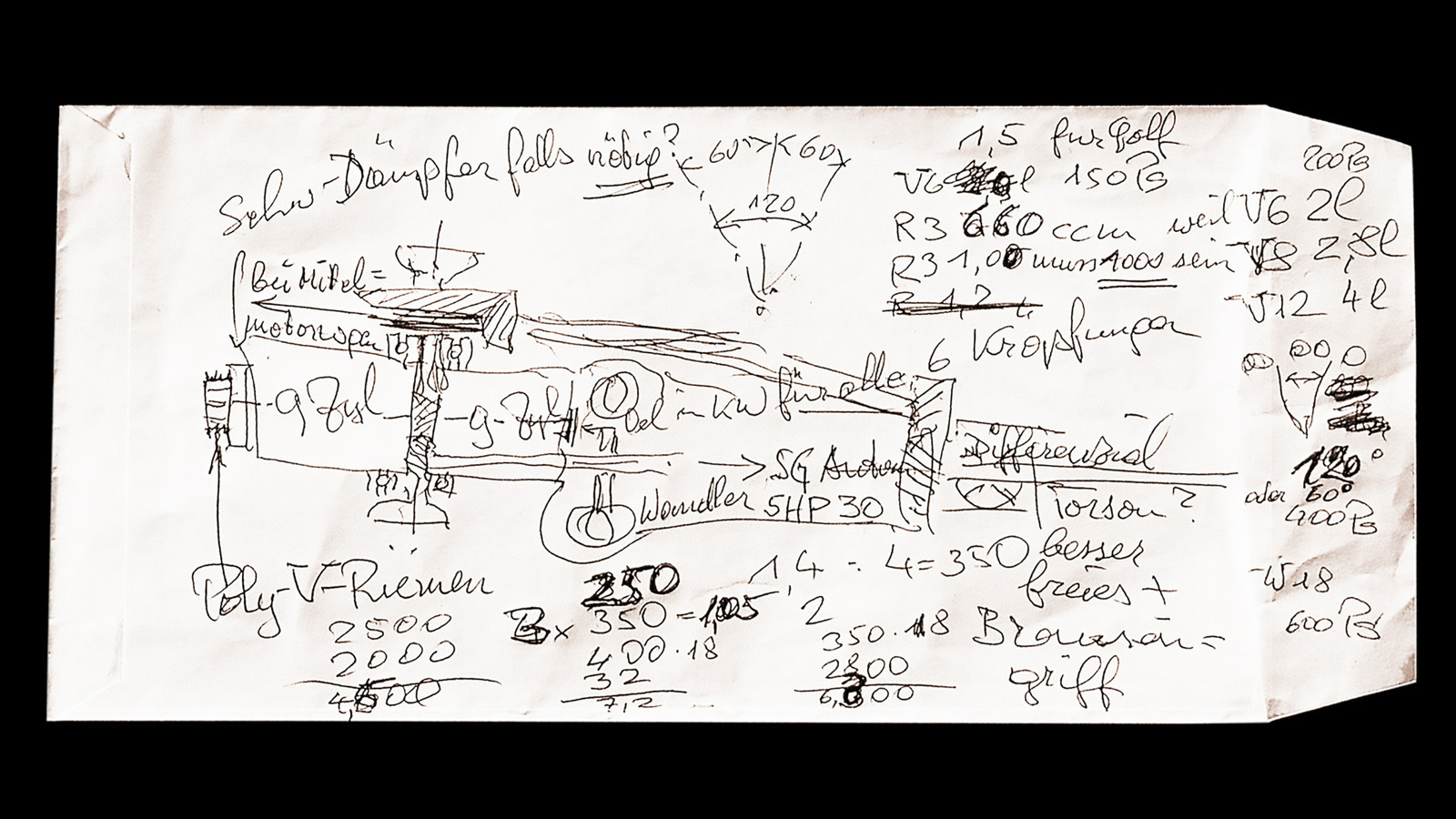

Spowers’ supercar will have a mechanical layout like no other, with the powertrain distributed rather than being front- or rear-engined.

It will be driven by four inboard electric motors (one per wheel). Electric power will come from a front-mounted hydrogen fuel cell and be stored in a rear-mounted 45kg array of supercapacitors (rather than a 500kg bank of heavyweight cells as used in a conventional battery-electric car).

The hydrogen tank, enough for a 400-mile range, will be sited behind the seats. Because of the unique powertrain and the lightweight construction it allows, the car will weigh just 620kg at the kerb instead of the 1400-1800kg of a battery alternative, which is why Spowers has dubbed his new enterprise as ‘Project Chapman’, invoking the name of the legendary Lotus founder who loved lightness and compactness above all.

The unique characteristics of fuel cell power give the car an extraordinary performance envelope – true supercar acceleration (0-100mph in just 6.4sec) but a top speed of just 100mph.

“The top speed isn’t ‘capped’,” explains Spowers. “It’s simply what the car can achieve with the size of fuel cell we’ve chosen. We think it’s enough.

"To go faster, we could fit a bigger fuel cell, which would lead to a bigger fuel tank, a larger and heavier structure, bigger motors and brakes, more supercapacitors: a whole weight-gain cycle would begin and the dynamic attributes that really matter would be compromised.

"In the design we have, the fuel cell is sized for a constant 100mph top speed, but that’s all there is.”

Spowers’ styling recipe is exacting. He wants his car to be modern and arrestingly beautiful in a timeless sense, avoiding the aggressive, “monsterish” look of current hypercars.

Its sophistication needs to help justify a high cost, well into hundreds of thousands. It must be a low supercar rather than a fuller-bodied GT; he wants its “look” to advertise its efficiency and lightness.

In October last year, Spowers laid down some design ‘hard points’ and Mahmud set the students to work. With these ‘customer requirements’ singing in their ears, they first set out to sketch their ideas freehand, developing them as CAD drawings and transferring that information to quarter-scale clay models, a task that even professional designers acknowledge as difficult. It’s one reason car makers’ design departments have specialist clay modellers.

The students were given eight weeks to take their designs from idea to presentation, in conjunction with other coursework. Just before Christmas, they presented their models to a judging panel consisting of Spowers and Mahmud plus Bentley head of interior design Darren Day (a Coventry alumnus), former Jaguar design chief Ian Callum and Riversimple consultant engineer Jim Router.

The students presented their work in a big Coventry display studio. Screens behind each model showed initial sketches and CAD developments.

In a procedure that seemed routine to Day and Callum but showed the rest of us the dispassionate assessments designers face in practice, each student was allowed just one minute to explain their design, whereupon the judges examined it and asked pertinent questions. The task was to select several finalists from 14 entries, then to choose a winner.

Judging was brisk, to the point of ruthlessness. That’s how it goes in professional design life, apparently. Time was taken over those that impressed; clear non-winners were glossed over.

This must have been an interesting lesson for the budding designers who weren’t given much time; an incentive to try harder next time. After all 14 were viewed, the students left the room while the judges selected finalists and a winner.

The standard of work was generally agreed to be high, especially since this project was an addition to the students’ regular curriculum. Even for a pro, Callum and Day agreed, it can be a tough assignment to translate good-looking sketches to a clay sculpture about a metre long.

Coventry regularly invites professional clay modellers in from nearby JLR to help teach its postgrad students but, despite it all, our professional designers often called for “more storytelling” in the designs.

The functioning of a lightweight and efficient car with a revolutionary propulsion system should be described in its shape; and lines that work attractively at the front of a car should be echoed and resolved on the sides and rear.

Spowers, especially, felt one common fault was the students’ tendency to propose shapes that were fuller, and “more GT-like” than he had in mind. And in some cases the best parts of the development sketches didn’t make it to the 3D model.

According to Callum and Day, that’s a fault that plagues even the professionals. It’s a reason why car design takes care and time, and why all car designers must become used to listening carefully to the opinions of critics, both bosses and peers.

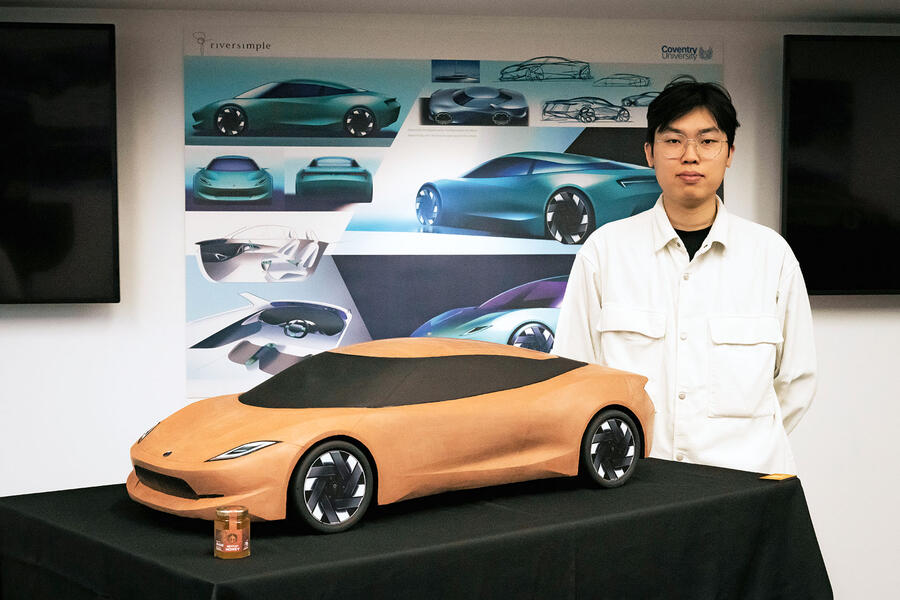

In the event, we finished up with four commended students from which we selected one winner, Haoyuan Bai, already an intern of Nio in Shanghai, China, whose nicely proportioned design featuring eye-catching rear spats was the universal choice.

Others commended were Zefan Shang and Yuyong Yin, also Chinese, and Bo Silkens from the Netherlands. Each of these was good enough to win, the judges felt, especially if they had made a better fist of the tough transition of turning attractive sketches into a 3D creation with the same visual appeal.

The important thing was that the design professionals’ winner was also the choice of Riversimple managing director Spowers. He particularly felt winner Bai had produced a design of unique appeal, which had got the “volumes” right: it wasn’t too tall or full in its sections, like some of the others, and it qualified as a proper supercar.

Having put quite a lot of time and effort into it, Spowers pronounced the design competition “a thoroughly positive experience”, though he acknowledged, just as the students did, that these were very much first steps.

He already builds functioning cars, knows how much more is involved in getting a new model on the road and is currently deciding what to do next.

What this exercise proved, above all, is that if a special car is to succeed, its styling must not only be visually arresting and satisfying but also play a big part in describing the car’s capabilities and the intentions of its creators.

And in this case, there is a particularly important story to be told.

Haoyuan Bai

Haoyuan Bai, 22, was attracted to car design when he first saw the 996-gen Porsche 911, and cites Pinky Lai (who led the car’s design) and Peter Schreyer (who transformed Kia into a ‘design’ brand) as his top influences.

Bai, a Nio intern, did his first design degree in Shanghai. The judges rated his Riversimple design, notable for its rear spats and for different design alternatives on either side of his model, for its excellent, ideal proportions for a Riversimple supercar, and for his very classy sketches.

Yuyong Yin

Among the advantages of studying at Coventry for Yuyong Yin, 24, is the university’s long design tradition, not to mention its proximity to the “legendary” Aston Martin and JLR factories.

A graduate in Environmental Design from China, he has already had internships at Geely and BYD, and says his ambition is “to design a car I could own forever”.

The judges rated his design principally for its cohesiveness – the front and rear shapes were very well matched – and were especially impressed given that this was his first shot at clay modelling.

Zefan Shang

Twenty-two-year-old Zefan Shang loves reading sci-fi and especially appreciates the designs of BMW’s former design chief Chris Bangle. He did his first degree in Coventry, qualifying with first-class honours.

When his postgrad study ends, he wants to be an exterior and concept designer, investigating “forward-looking” transport solutions for a big car manufacturer.

His design has an eye-catching plane surrounding its front wheel arch that impressed the judges, several of whom noted that the car seemed more cab-forward in the model than the drawings, which were Zefan’s best work.

Bo Silkens

Bo Silkens is a 23-year-old exchange student from TU Delft in the Netherlands, where his famous countrymen Adrian van Hooydonk (BMW Group design chief) and Laurens van den Acker (head of design at the Renault Group) were educated.

He came to Coventry to improve skills such as clay modelling and he describes the experience as “awesome”.

The judges liked his design for its appropriate “volume” and for the way the side pods described the car, though they felt these could be further developed to enhance the story of the car’s purpose and its mechanicals.

.jpg)