The $35 billion question: Is SBIR funding delivering for America’s warfighters?

Congress has an opportunity this fall to clarify the purpose of the Small Business Innovation Research effort, write Jon Chung and Dan Berkenstock.

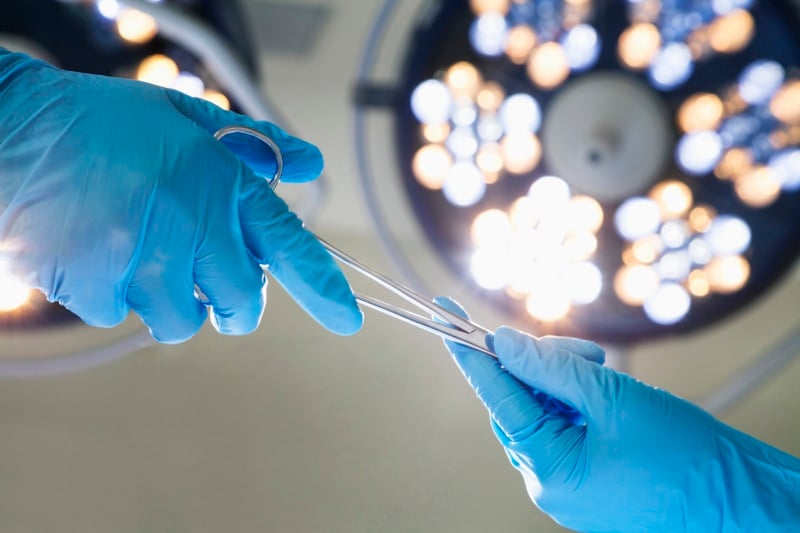

A small business leader (right) speaks to Letterkenny employees during LEAD SBIR Depot Day July 9. As part of the U.S. Army’s Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program, Letterkenny Army Depot leadership hosted 10 U.S. small businesses for the first-ever Letterkenny SBIR Depot Day. (Photo by Pam Goodhart)

What is the purpose of the $35 billion the Department of Defense has invested in Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) over the past 40 years — and the $1.5 billion it will award annually moving forward? Should success be measured by the number of small businesses funded and jobs created, or by the operational capabilities delivered to warfighters?

With SBIR authorization set to expire this fall, Congress has a rare opportunity to provide strategic clarity on an effort that is a major tool for pushing advanced technologies into the Pentagon. If the goal is delivering new capabilities at the speed of relevance, then SBIR — and programs like it — must be aligned with the private-sector forces driving the next wave of national defense innovation.

A strong step in that direction would be passing a reauthorization bill that includes the Strategic Breakthrough Funding (SBF) program, as recently proposed by Sen. Joni Ernst in the INNOVATE Act. This program, which would provide up to $30 million in SBIR funds when matched with non-SBIR government contracts and/or private capital, would immediately supercharge the small business defense industrial revolution.

Created through the Small Business Development Act of 1982, SBIR is funded as a carve-out from extramural R&D budgets — making it one of the largest pools of DoD development funding not tied to congressional line items. The program was intended to harness the innovation potential and agility of small businesses in meeting federal R&D needs, particularly in accelerating new technology to tackle pressing national security challenges.

For its first 25 years, the program was focused on early-stage innovation — funding feasibility studies and system prototyping. The underlying assumption was that companies completing Phase II prototyping would be ready for program offices to take over, transitioning promising technologies into acquisition programs.

By the mid-2000s, it became evident that this assumption was flawed. Too many companies had good ideas and working prototypes, but no path forward. The bridge to operational adoption didn’t exist. In response, Congress passed the SBIR Reauthorization Act of 2011, introducing a series of reforms that aimed to fix the so-called Valley of Death, where businesses struggle to get from prototype to program adoption. These new authorities included the ability to award sequential Phase II grants, support later-stage technology transition, and match SBIR funding with program office dollars and/or private capital.

The most visible outcome of these reforms is the Strategic Funding Increase (STRATFI) program, administered by AFWERX and SpaceWERX. STRATFI awards match up to $15 million in SBIR funds in a 1:1:2 ratio among SBIR, DoD program offices, and private investors — enabling total awards of up to $60 million. More than 65 companies have received STRATFI funding to date, building systems ranging from smart rifles to hypersonic vehicles.

The authorities contained in the 2011 language have coincided with the rise of a new generation of highly capable small businesses. Today, more than 200 venture-backed defense startups are tackling some of the most critical national security challenges across space, autonomy, cyber, and advanced manufacturing. These companies are staffed with top engineers from both Silicon Valley and the traditional defense base. They’re fast, focused, and fiercely mission-driven — demonstrating a new model for capability development that begins with commercially viable technology and ends with deployable systems.

A typical hardware startup delivers its first operational capability after about one million hours of labor, mostly engineering, funded almost entirely by private investors. Multiply that by 200+ companies in today’s defense innovation ecosystem and you’re looking at over 200 million hours of cutting-edge technical work — a resource America’s national security establishment fails to fully embrace at significant risk.

But startups are also on a clock. Capital comes in waves, often in 24-month cycles, with increasing expectations at each stage. A company might close a $25 million Series A round based on $10 million in contracts or bookings. To raise a $40–50 million Series B — often the round that carries a company to fielded capability — it may need $20 million or more in booked annual revenue. Government contracts act as a demand signal, not just for procurement, but for investors, too. Missed signals have real consequences.

Programs like STRATFI are a good start — but to truly align with the tempo and scale of private investment, the current model needs refinement. First, STRATFI currently spans four years and is limited to $15 million SBIR dollars. Venture-backed companies operate on two-year fundraising timelines and need two distinct award moments, spaced roughly two years apart, to sustain investor confidence. Additionally, each sequential award should be larger than the previous one to match venture expectations of revenue milestones. Hence, STRATFI should be modified to provide two distinct awards of increasing dollar value, spaced two years apart so that government-derived revenues match expectations of venture investors at each of the various investment stages.

Second, current rules allow companies to count past investments as matching funds. Instead, legislation should require that matching dollars be raised after award notification — making the award itself a catalyst to force additional investment commitments.

Finally, STRATFI is currently just a Department of the Air Force program. Acquisition executives across the other military departments should have access to similar tools to fully benefit from the emerging innovation ecosystem.

The good news is that none of this requires sweeping acquisition reform. Most of these improvements — and several others — are already included in the Strategic Breakthrough Funding program proposed in the INNOVATE Act. Strategic Breakthrough Funding would raise matching caps to $30 million, reduce red tape, and make funding more accessible across the Department of Defense.

With a few key refinements, this approach could become the framework that aligns the SBIR program with private investment in order to unlock the full potential of America’s defense innovation base — an urgent national priority in an increasingly dangerous world.

Jon Chung is a US Space Force Fellow at the MITRE Corporation. Dan Berkenstock is a Distinguished Research Fellow at the Hoover Institution. Together, they are authors of the recent Hoover paper “The Warfighter’s Pipeline: A Blueprint for Aligning Defense Acquisition with Venture Capital.”

Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of The Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency.

.jpg)