This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

All

Agriculture and Farming

Agriculture and Food News -- ScienceDaily

CropLife

Farming Today

Modern Farmer

National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition

Farming Was Extensive in Ancient North Americ...

Jun 7, 2025 0

Lecithin Market to Redefine the Future of the...

Jun 6, 2025 0

Lecithin Market to Redefine the Future of the...

Jun 6, 2025 0

Farming Was Extensive in Ancient North Americ...

Jun 7, 2025 0

It’s Not Just Poor Rains Causing Drought. The...

Jun 4, 2025 0

14 Million Honeybees Escape After a Truck Rol...

Jun 3, 2025 0

A Peach and Apple Farmer’s Uphill Quest to Fe...

Jun 2, 2025 0

All

Autoblog

Autocar RSS Feed

Automotive News Breaking News Feed

Automotive World

Autos

Electric Cars Report

Jalopnik

Automotive News | AM-online

Speedhunters

The Truth About Cars

Nissan: Welcome to the All-New Silence S04 Na...

Jun 6, 2025 0

Stellantis Ventures showcases start-up collab...

Jun 6, 2025 0

All

All Stories

All Stories

BioPharma Dive - Latest News

Breaking World Pharma News

Drugs.com - Clinical Trials

Drugs.com - FDA MedWatch Alerts

Drugs.com - New Drug Approvals

Drugs.com - Pharma Industry News

FDA Press Releases RSS Feed

Federal Register: Food and Drug Administration

News and press releases

Pharmaceuticals news FT.com

PharmaTimes World News

Stat

What's new

Application of machine learning in drug side ...

Jun 7, 2025 0

Tea, berries, dark chocolate and apples could...

Jun 7, 2025 0

Application of machine learning in drug side ...

Jun 7, 2025 0

Tea, berries, dark chocolate and apples could...

Jun 7, 2025 0

Collaborations result in antibiotic resistanc...

Jun 7, 2025 0

Fighting myeloma with fiber: Plant-based diet...

Jun 7, 2025 0

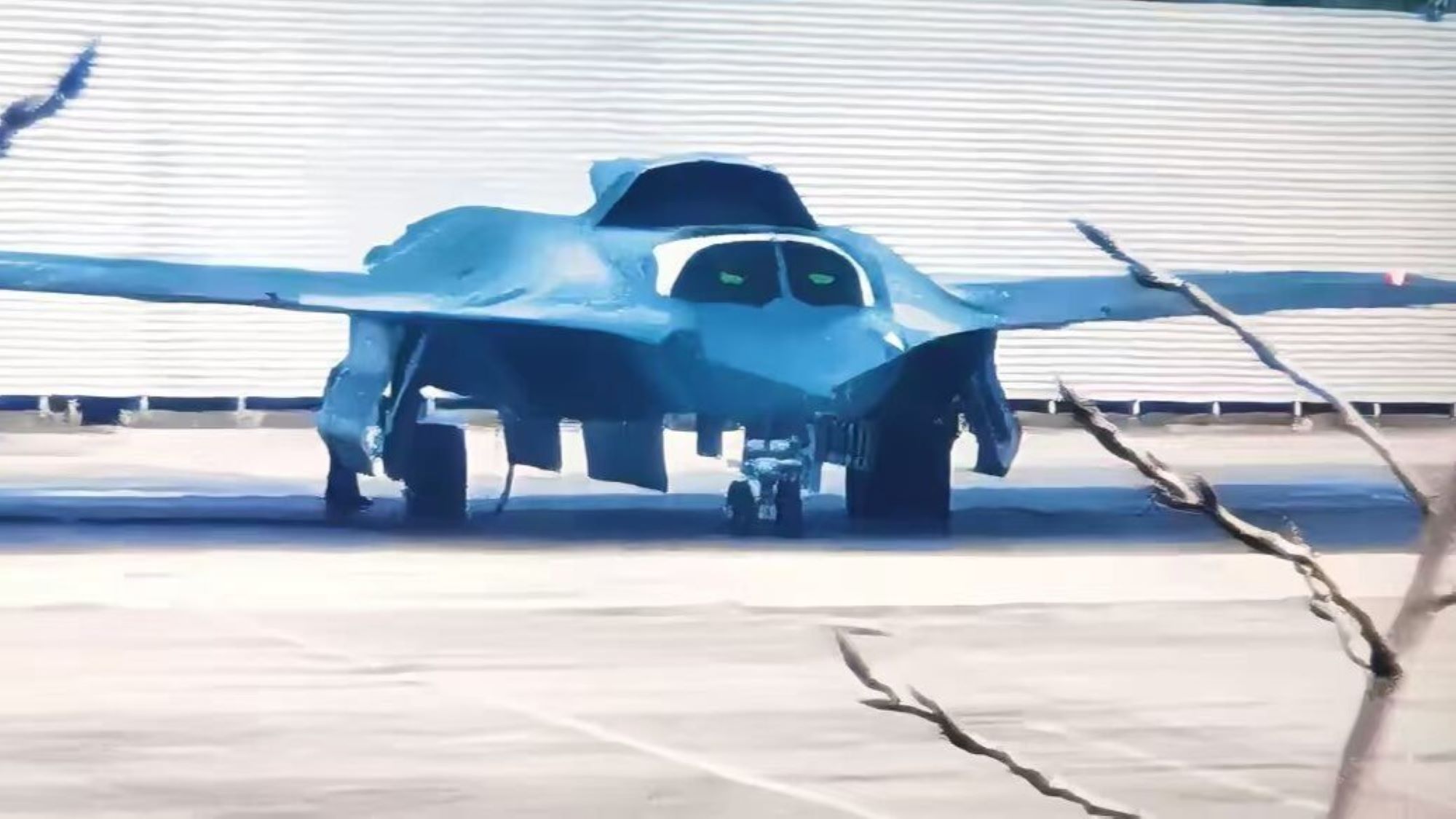

All

Breaking DefenseFull RSS Feed – Breaking Defense

DefenceTalk

Defense One - All Content

Military Space News

NATO Latest News

The Aviationist

War is Boring

War on the Rocks

NATO and Azerbaijan strengthen cooperation on...

Jun 6, 2025 0

NATO Military Committee Visits Luxembourg

Jun 6, 2025 0

NATO Partnership and Cooperative Security Com...

Jun 6, 2025 0

NATO Defence Ministers agree new capability t...

Jun 5, 2025 0

All

Advanced Energy Materials

CleanTechnica

Energy | FT

Energy | The Guardian

EnergyTrend

Nature Energy

NYT > Energy & Environment

PV-Tech

RSC - Energy Environ. Sci. latest articles

Utility Dive - Latest News

Modeling Short‐Range Order in High‐Entropy Ca...

Jun 7, 2025 0

Aloe‐Derived Sustainable, Aqueous and Flame R...

Jun 6, 2025 0

A Novel Quantification Method for High Voltag...

Jun 6, 2025 0

Interior Morphology and Pore Structure in Hig...

Jun 5, 2025 0

- Contact

- LIVE TV

- Agriculture

- Automotive

- Beauty

-

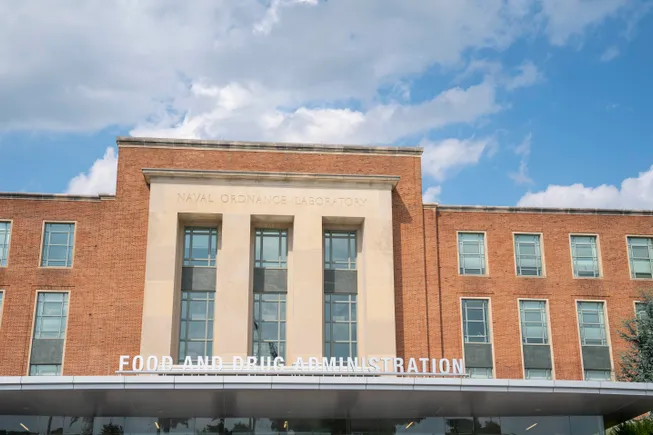

Biopharma

- All

- All Stories

- All Stories

- BioPharma Dive - Latest News

- Breaking World Pharma News

- Drugs.com - Clinical Trials

- Drugs.com - FDA MedWatch Alerts

- Drugs.com - New Drug Approvals

- Drugs.com - Pharma Industry News

- FDA Press Releases RSS Feed

- Federal Register: Food and Drug Administration

- News and press releases

- Pharmaceuticals news FT.com

- PharmaTimes World News

- Stat

- What's new

- Defense

- Energy & Water

- Fashion

- Food & Beverage

- Healthcare

- Legal

- Manufacturing

- Luxury

- Medical Devices

- Mining

- Real Estate

- Retail

- Science Journals

- Transport & Logistics

- Travel & Hospitality