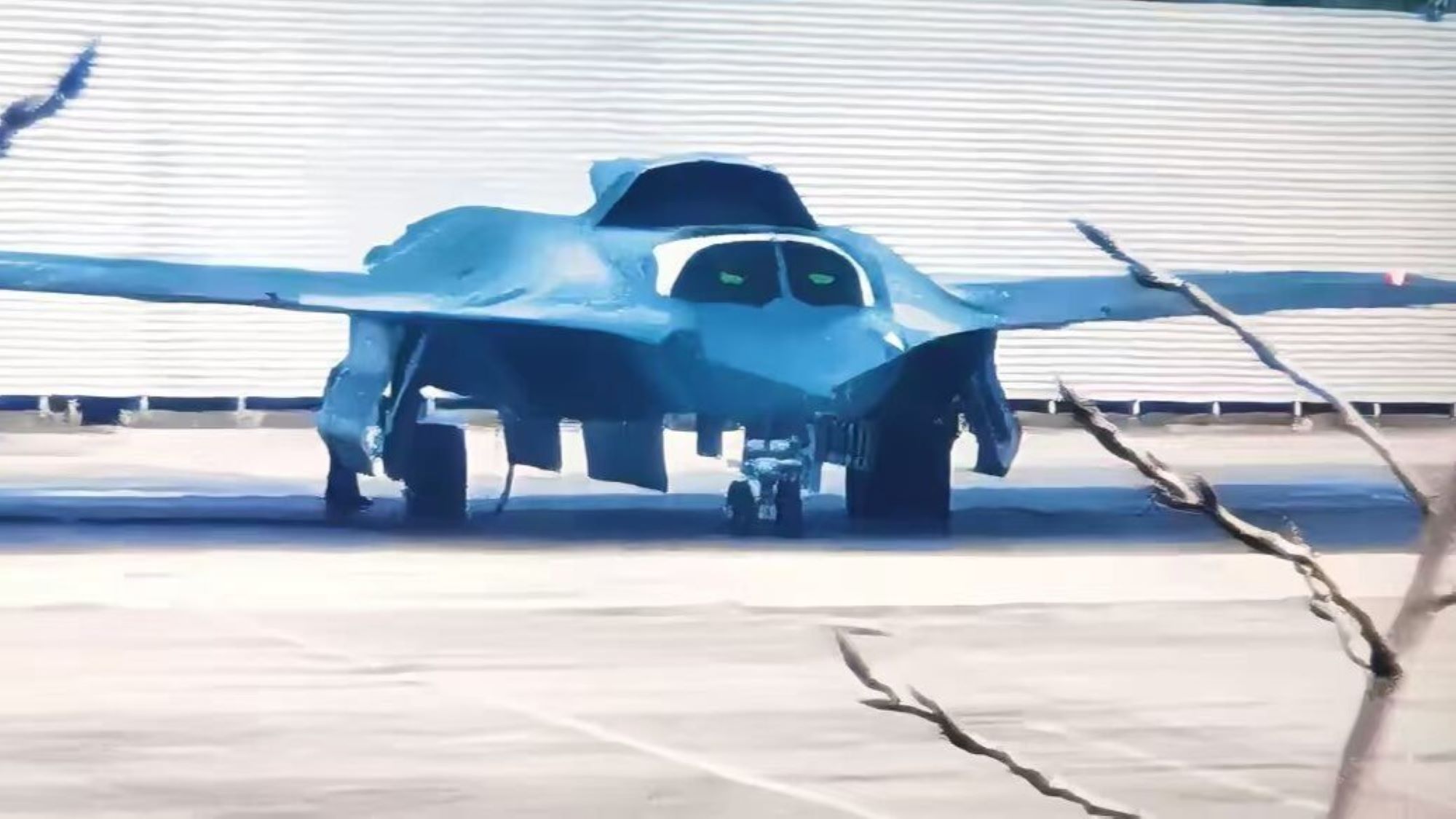

Naval drone startup HavocAI hopes to build 100-foot robot boat by year’s end

The company is on track to deliver a 42-foot uncrewed vessel this summer, says CEO Paul Lwin.

“We're going to take a 42 foot vessel that is built for the Pacific, and we're going to make it autonomous…and collaborate with the Rampages [HavocAI’s small USVs] to do missions. And by the end of 2025 we'll put [a] 100-foot USB into the water,” Paul Lwin, HavocAI’s CEO and co-founder, told Defense One.

Thirty-two of Havoc AI’s robot boats are already with DOD customers across the globe—in Europe, the U.S. east and west coasts, and in Hawaii. The company is building a 38-foot vessel and, thanks to a new deal with PacMar Technologies, is planning to build a 42-foot autonomous vessel “that is built for the Pacific,” Lwin said.

“Now that the software is mature, we're going to put it on bigger and bigger boats,” he said.

HavocAI focuses on the robot brains of uncrewed surface vessels, partnering with existing shipyards to build them. During the Army’s annual tech demonstration, Project Convergence, HavocAI attached its autonomous software onto “essentially a pontoon boat that landed on the beach… to show that our software doesn't care what kind of boat it is.”

Lwin said the exercise was the first time the company had demonstrated that capability outside of internal testing. But after trying it on about seven different vessels, the goal is to go bigger, fast.

Uncrewed vessels are having a moment. As the military operational uses become clearer, the Navy is leaning into the technologies to see what they can do and companies are champing at the bit to prove themselves not only on the technology front, but also in manufacturing capability.

For example, Aerial drone maker Red Cat recently expanded with a new line of USVs that the U.S. Navy will test this summer. And robot boat startup Saronic recently announced its plans to produce a 150-foot uncrewed surface vessel, and picked a shipyard to start building it in the next year. The company is still looking for a site to house its Port Alpha facility, which would churn out large USVs that are hundreds of feet long.

From Ukraine to INDOPACOM

Ukraine’s use of drones across domains has reshaped modern warfare. In the maritime domain, Ukraine has used surface and subsea drones to attack Russian assets and infrastructure; Ukrainian drone boats reportedly intercepted a manned Russian aircraft in early May.

“There's a wide range of potential concepts of employment, some of which the [U.S.] Navy already uses,” such as launching weapons, deception, laying sensors for anti-submarine warfare, carrying smaller vehicles, and electronic warfare, said Scott Savitz, a senior engineer with RAND. “And unlike UUVs, they've got the ability to get comms and satellite navigation from the ambient environment. So there's a lot that can be done.”

But what advantage would a 42-foot USV have over one that is just a few feet shorter, especially in the vast Pacific? What about 100 feet?

“Endurance,” Savitz said. “Depending on how much of that you fill with fuel versus payload, that can enable you to transit immense distances both to and within the Indo-Pacific region. The second piece is that sometimes you're going to want large payloads. If you're, say, launching smaller vehicles, or if you want to have a substantial battery of weapons that you can fire. Everything takes up space. Everything requires power.”

That extra 10 percent in length, assuming everything is scaled in proportion except the engine, could add 35 percent more volume and room for payloads, he said.

“So, bigger is better in some respects. Of course, it also likely increases radar cross-section, and you start getting into trade-offs of…vulnerability to attack,” Savitz said.

When attack risk is high, the Navy may need to rely on smaller USVs with shorter ranges, when the goal is to “overwhelm with numbers,” whereas a larger USV could be used in a more uncontested space.

For Lwin, the idea would be to use big USVs to enhance a destroyer’s capability, keeping crew back at a safe distance.

A guided missile destroyer ship or DDG, which costs around $4 billion, can’t get too close to an island in the South China Sea without entering missile range, he said.

“If a DDG goes close and the missile hits it, that's 150 people’s lives lost,” Lwin said.

But a weapon-strapped MUSV that costs $100,000 to build will force China to use seven-figure missiles, “so they'll run out of missiles to shoot the DDG. The whole time, thousands of these smaller vessels have sensors on them and are…feeding [data] back to that DDG. So when it is able to come in, they already have targeting solutions. They know what the common operating picture is, and they can be a part of the fight.”

HavocAI’s 42-foot USV is scheduled to hit the water in July, and begin testing its collaboration with smaller vessels in its portfolio—which all run the same software—for missions.

“All three of those—that 100-foot, the 42-foot, the 38-foot and the 14-foots—they’re running the same software, so they can collaborate with each other and do very sophisticated missions together.”

Lwin gave Defense One a peek at HavocAI’s dashboard, selecting a section of ocean to send eight boats to search for a target. The little triangle-like boat images wiggled awake before making their way across the screen to the search area. The idea is to have 1,000 small USVs teamed with maybe 100 bigger ones, to act as a “heterogeneous maritime fleet to counter some of the Chinese threats. So that's what we're going to do for the rest of this year,” he said.

Navigating choppy waters

Congress is getting behind the idea of naval drones: the Senate version of the “One Big Beautiful Bill”—a sweeping tax and budget reconciliation package—earmarks $1.5 billion to expand small USV production and $2.1 billion to prototype, buy and integrate “purpose-built” medium USVs. The House-passed bill allots for $1.5 billion and $1.8 billion respectively.

But the level of trust in employing the technology broadly may look different depending on the mission, conflict, or scenario.

“There may also be a less permissive set of rules of engagement for the United States when it's not fighting in an existential war, whereas Ukraine may have a higher tolerance for accidentally targeting the wrong thing. So it will be different, and the United States may impose additional restrictions” when operating USVs around US or allied forces to avoid loss of life.

But there are also technical difficulties that have to be ironed out. One of the biggest challenges ahead for HavocAI will be building the digital control systems with PacMar and understanding how to digitally control a maritime vessel in a way that makes it operationally relevant, Lwin said.

“The challenge is coming up with the autonomous behaviors to make those 42-foot vessels a weapon,” Lwin said, adding that the company is working with defense prime contractors to figure out how to launch legacy missiles, using legacy targeting systems, off of the planned 100-foot uncrewed vessel.

“How do you integrate proven weapons, kinetic weapons, that work with autonomous systems and do this human-machine teaming, and what the Navy is calling the hybrid fleet?” he said.

There’s also the challenge of keeping USVs upright and avoiding collisions, Savitz noted.

“Those are two key critical ones, but also the autonomy has to be smart enough to address whatever the needs of the particular mission are, whether it's deception, logistics, electronic warfare, launching weapons, including both missiles and torpedoes, or dropping mines,” he said.

“This is much more of a niche capability… In this environment, there are people who are actively seeking to disrupt in any way possible, so trying to achieve the kind of autonomy that has so far been elusive, or that we are just coming to grasp in some limited contexts on the ground, is going to be that much harder and that much more expensive and just require a lot of time to develop.” ]]>