Sketching 300mph: The aero secrets of the Hennessey Venom F5

Hennessey Venom F5 is aiming to reach a top speed of 310mph-plus Designer of one of the world's fastest cars explains how designs can bend the laws of physics Ever wondered why so many supercars claim a ‘217mph-plus’ top speed? The McLaren P1, LaFerrari and Lamborghini Revuelto are just a trio of heavy-hitting examples. An easy, clean conversion to a mite under 350kph is one possible reason. Another explanation, however, is aerodynamics. “There’s an exponential increase in difficulty and complexity beyond 220mph,” says Nathan Malinick, Hennessey’s director of design. “Most hypercars can do that no problem, but 250mph and above remains very, very difficult. You have to know what you’re doing.” His most dramatic work so far is the Hennessey Venom F5, its target to be the fastest production car in the world. Its theoretical 310mph-plus top speed (itself a neat 500kph) will outstrip Bugatti and Koenigsegg should it come to fruition, but Malinick is only too familiar with the soaring aerodynamic challenges as you try to surpass the triple-ton – at which point you’re covering a mile every 12 seconds and pushing tyre technology to its very margins. Handily, his CV includes work in the aerospace industry. “We are a comparatively small company and we have to be extremely efficient. If our target was closer to 200mph then the requirements would be totally different. That’s still fast, but it’s nothing like 300, which is getting more into the aerospace side of things versus automotive,” he says. “There is quite a bit of crossover. From an aesthetic and philosophical standpoint, the F5’s interior is relatable to some of the cockpits that I was working on in my previous role. Simplicity drives a lot of what we do; on the exterior, it drove things in maybe unusual ways. One instance would be a lack of active aerodynamics, because we didn’t want to have an aspect of the car that would be susceptible to a failure at such high speeds. “You’re not going to see the flicks and blades of an F1 car on an F-35 or F-22 jet. Likewise, you’re not going to see them on our car because they contradict its purpose of top speed.” Supercars mostly sell on glamour, so how easy is it for Malinick to ensure his team’s designs are beautiful enough to be coveted by the collectors with the requisite millions to buy one? “We’re lucky to have creative engineers who recognise the value of design and want to support it, because ultimately people buy with their eyes,” he says. “The kind of people we’re talking to already have one of everything. Our car needs to pull on their heartstrings. “Our design and engineering teams work hand in hand. It’s not like we progress a design element and then say: ‘Hey engineering, take a look and see what you think.’ Feedback is in real time. We might need to stop and take something into CFD [computational fluid dynamics], or rapid-prototype something in the wind tunnel to ensure there’s no time lost. “The engineers are helpful in saying ‘this area of the car is not as significant, so do whatever you want here’. But sometimes our design will be dictated by function. Some of that is neat: a purely engineering-driven detail underneath the car that you’re not going to see unless it’s jacked up on a lift.” Despite its lofty goals and Malinick’s aerospace past, the Venom F5 can still thank pencil and paper for its design. “I do a ton of sketching,” admits Malinick. “It’s my favourite part of the process. I probably have thousands and thousands of sketches, whether it’s F5 or what we’re moving onto next.” It’s bait I can’t resist taking: what is coming next? He says: “If the F5 is all about performance, the next car is about driving interaction. It’s not going to be as powerful; it doesn’t need to be. "The feedback we’ve had from customers and dealers has been really strong. It’s very much the antithesis to the digital age of cars we find ourselves in.” Does that mean it’s a manual? “If the customers come back and say ‘we want a DCT’, okay, that’s fine,” he says. “But as of now, I’d say it’s analogue to the nth degree.” Which suggests it will be free of the Venom’s turbocharging. “We’re still determining that,” says Malinick, “but we’re leaning towards something free of forced induction for the purity of it all. "We want something very, very high-revving.” Sounds like a noble target to us.

Hennessey Venom F5 is aiming to reach a top speed of 310mph-plusDesigner of one of the world's fastest cars explains how designs can bend the laws of physics

Ever wondered why so many supercars claim a ‘217mph-plus’ top speed? The McLaren P1, LaFerrari and Lamborghini Revuelto are just a trio of heavy-hitting examples.

An easy, clean conversion to a mite under 350kph is one possible reason. Another explanation, however, is aerodynamics.

“There’s an exponential increase in difficulty and complexity beyond 220mph,” says Nathan Malinick, Hennessey’s director of design. “Most hypercars can do that no problem, but 250mph and above remains very, very difficult. You have to know what you’re doing.”

His most dramatic work so far is the Hennessey Venom F5, its target to be the fastest production car in the world.

Its theoretical 310mph-plus top speed (itself a neat 500kph) will outstrip Bugatti and Koenigsegg should it come to fruition, but Malinick is only too familiar with the soaring aerodynamic challenges as you try to surpass the triple-ton – at which point you’re covering a mile every 12 seconds and pushing tyre technology to its very margins. Handily, his CV includes work in the aerospace industry.

“We are a comparatively small company and we have to be extremely efficient. If our target was closer to 200mph then the requirements would be totally different. That’s still fast, but it’s nothing like 300, which is getting more into the aerospace side of things versus automotive,” he says.

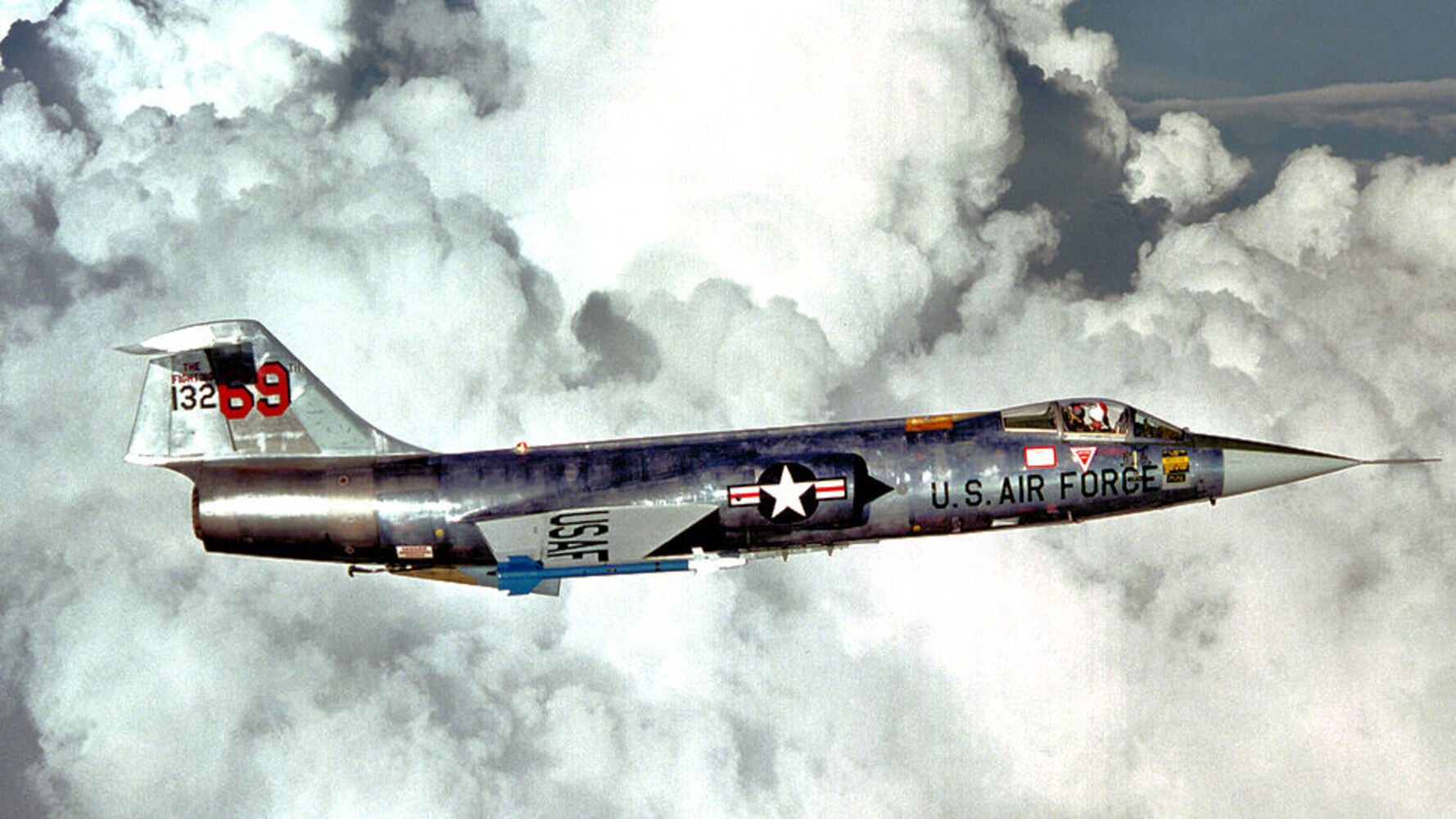

“There is quite a bit of crossover. From an aesthetic and philosophical standpoint, the F5’s interior is relatable to some of the cockpits that I was working on in my previous role. Simplicity drives a lot of what we do; on the exterior, it drove things in maybe unusual ways.

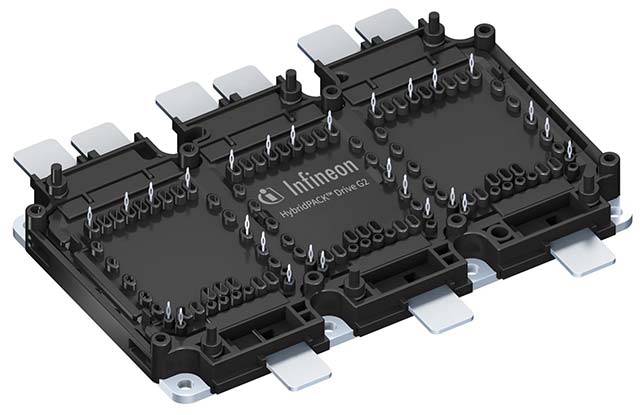

One instance would be a lack of active aerodynamics, because we didn’t want to have an aspect of the car that would be susceptible to a failure at such high speeds.

“You’re not going to see the flicks and blades of an F1 car on an F-35 or F-22 jet. Likewise, you’re not going to see them on our car because they contradict its purpose of top speed.”

Supercars mostly sell on glamour, so how easy is it for Malinick to ensure his team’s designs are beautiful enough to be coveted by the collectors with the requisite millions to buy one?

“We’re lucky to have creative engineers who recognise the value of design and want to support it, because ultimately people buy with their eyes,” he says. “The kind of people we’re talking to already have one of everything. Our car needs to pull on their heartstrings.

“Our design and engineering teams work hand in hand. It’s not like we progress a design element and then say: ‘Hey engineering, take a look and see what you think.’ Feedback is in real time. We might need to stop and take something into CFD [computational fluid dynamics], or rapid-prototype something in the wind tunnel to ensure there’s no time lost.

“The engineers are helpful in saying ‘this area of the car is not as significant, so do whatever you want here’. But sometimes our design will be dictated by function. Some of that is neat: a purely engineering-driven detail underneath the car that you’re not going to see unless it’s jacked up on a lift.”

Despite its lofty goals and Malinick’s aerospace past, the Venom F5 can still thank pencil and paper for its design. “I do a ton of sketching,” admits Malinick. “It’s my favourite part of the process. I probably have thousands and thousands of sketches, whether it’s F5 or what we’re moving onto next.”

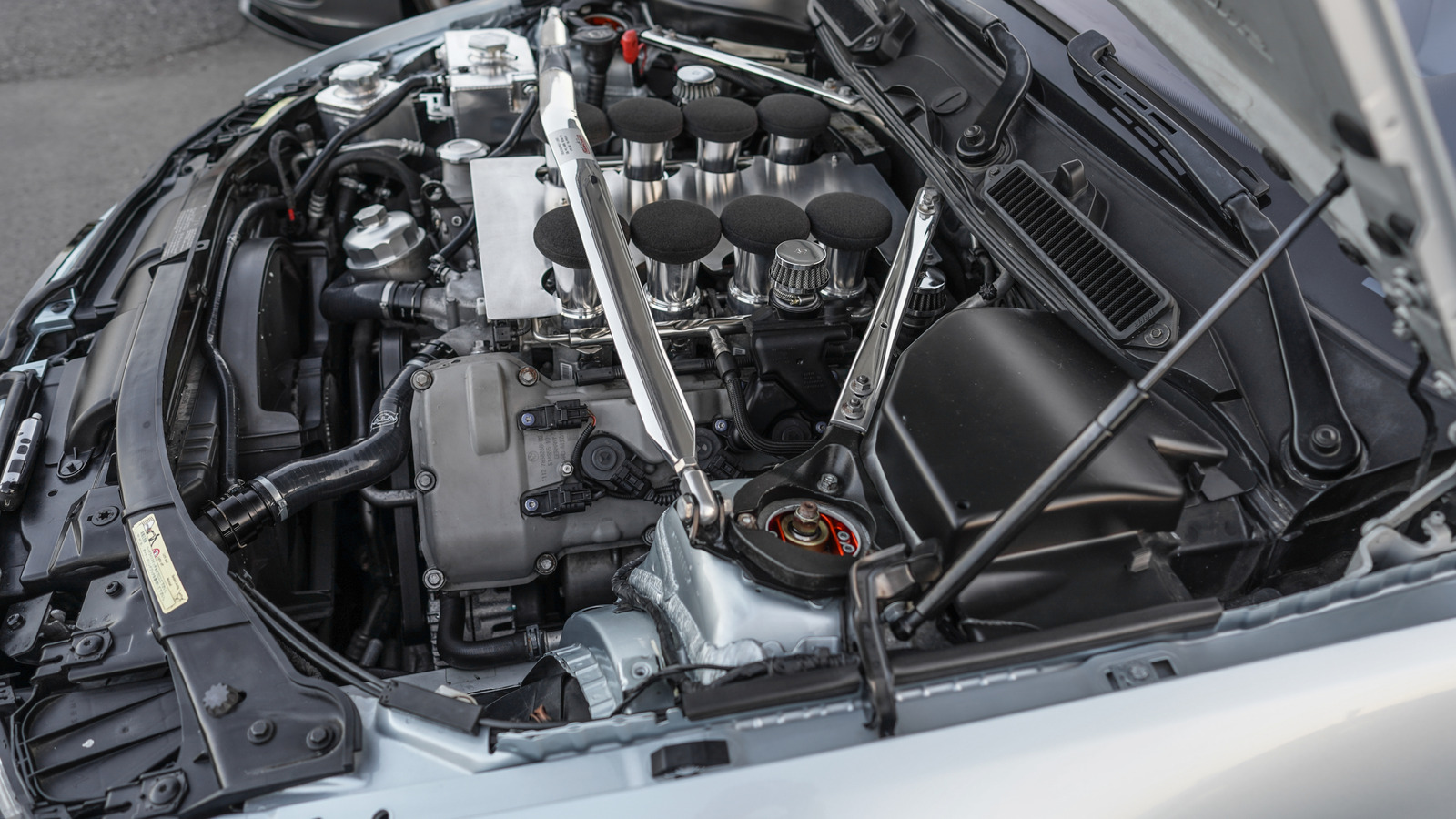

It’s bait I can’t resist taking: what is coming next? He says: “If the F5 is all about performance, the next car is about driving interaction. It’s not going to be as powerful; it doesn’t need to be.

"The feedback we’ve had from customers and dealers has been really strong. It’s very much the antithesis to the digital age of cars we find ourselves in.”

Does that mean it’s a manual? “If the customers come back and say ‘we want a DCT’, okay, that’s fine,” he says. “But as of now, I’d say it’s analogue to the nth degree.”

Which suggests it will be free of the Venom’s turbocharging. “We’re still determining that,” says Malinick, “but we’re leaning towards something free of forced induction for the purity of it all.

"We want something very, very high-revving.” Sounds like a noble target to us.