Shein versus Vestiaire Collective: the ideological (and economic) battle over fast fashion

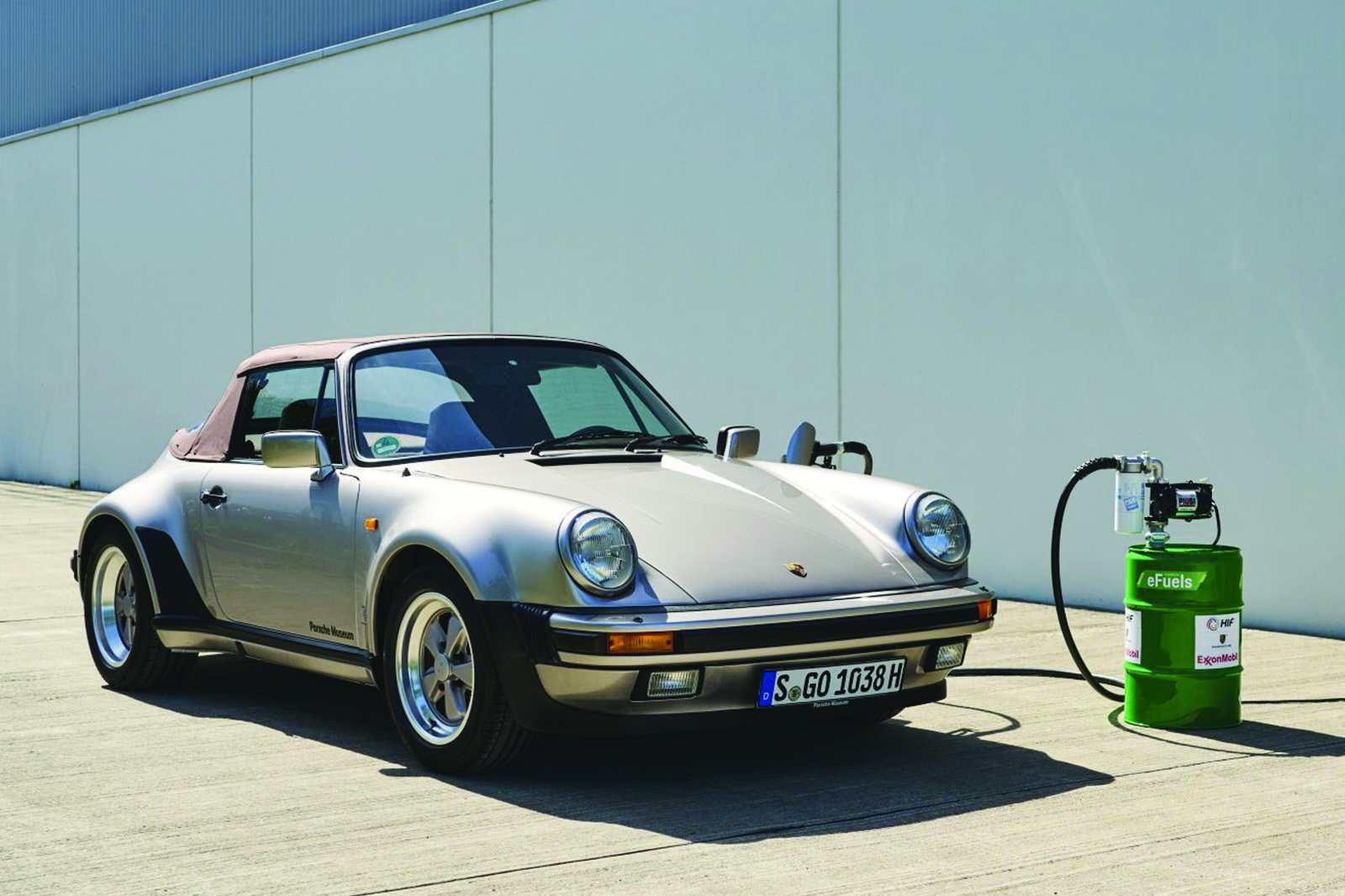

Vestiaire Collective 2025 campaign. Credits: Vestiaire Collective France - Two irreconcilable visions of have fashion clashed. On one side, Shein, a Chinese ultra-fast fashion giant, advocated for fashion “accessible to all”. On the other, Vestiaire Collective, a French pioneer of high-end second-hand fashion, denounced a toxic promise based on social exploitation, textile waste and the endangerment of an entire industrial ecosystem. “Fashion for all, misery for a few.” With this slogan, Vestiaire Collective responded to recent Shein’s advertising campaigns, which defended a vision of fashion as a “fundamental right”, affordable for all budgets. According to Vestiaire Collective’s chief impact officer, Dounia Wone in a post on LinkedIn, the real cost of this right is much higher than the price tag: sacrificed local employment, erased textile know-how and a polluted planet. The promise of “democratising” fashion was built on working conditions denounced as abusive. A seductive economic promise, but unsustainable? Shein conquered the world with a simple formula: thousands of items, updated in real time, at ultra-competitive prices. A dress for 12 euros, delivered in 72 hours, returned if necessary or thrown away. Behind this impressive logistics operation was a model based on a frantic pace of production, up to 75 hours of work per week in workshops denounced by several non-governmental organisations, and a return rate so high that it justified the burial or incineration of unsold new clothes. Vestiaire Collective directly attacked this logic: “Why should fashion be disposable?” the brand asked in its campaigns. It stated that this model did not include any real costs, neither for the environment, social rights, nor local economies. Vestiaire Collective, activist and activated Vestiaire Collective’s attack did not stop at slogans. From 2022, the platform progressively banned more than 70 fast fashion brands, including Shein, Zara, Boohoo, H&M and PrettyLittleThing. This strategy went against the imperatives of volume in e-commerce, but seemed to be paying off. According to the platform, 92 percent of buyers remained active after these decisions, as it banked on the upgrading of the second-hand market. The company no longer hid that it was now a political player. It actively campaigned for stricter regulation of the textile sector, particularly against Asian fast fashion giants. The anti-fast fashion bill, led by member of parliament Anne-Cécile Violland, which included a bonus-malus system and a limitation on advertising for polluting brands, was in its sights. This bill was buried in March 2025 in a chilling political silence. Lobbying, appointments and grey areas The controversy was reignited with the surprise appointment of Christophe Castaner, former minister of the interior, to Shein’s corporate social responsibility strategic committee. For Vestiaire Collective’s co-founder, Fanny Moizant, this was a “national scandal”. She stated that this arrival strangely coincided with the withdrawal of the bill. “Shein was very clever. They defused a regulation that would have cost millions,” she told Madame Figaro. According to Moizant, France could have become a world leader in the regulation of disposable fashion, and Shein had stopped at nothing to prevent this. A war of narratives as much as a clash of models This duel highlighted two antagonistic narratives around consumption: Shein sold speed, novelty and accessibility, at the price of an opaque and controversial industrial model. Vestiaire Collective defended sustainability, quality and circularity, at the price of educating consumers and a profound cultural change. But this battle was not limited to public statements, it already influenced legislative work. Law that caused debate Despite the initial withdrawal of the anti-fast fashion bill, mobilisation continued to put pressure. Under the effect of intense media coverage and growing indignation, the law was revised and put back on the parliamentary agenda, albeit in a watered-down version. While the bonus-malus was retained, the maximum tax was lowered, and advertising restrictions were relaxed. This was a partial victory for advocates of more responsible fashion, but a clear signal that pressure worked. A sign of the times: leading figures in French fashion were now taking a public stand. From couture houses to independent labels, several industry leaders in turn denounced the Shein model, praised Vestiaire Collective’s courage and called for structural reform. This dynamic could mark a turning point: criticism of ultra-fast low-cost was no longer only voiced by activists, but was becoming an image issue for established players in French fashion. Shein counter-attacked, French fashion retaliated As the anti-fast fashion bill approached its examination in the Senate, scheduled for June 10, Shein went on the offensive. Aware of the regulatory threat, the Chinese brand launched a vast advertising cam

France - Two irreconcilable visions of have fashion clashed. On one side, Shein, a Chinese ultra-fast fashion giant, advocated for fashion “accessible to all”. On the other, Vestiaire Collective, a French pioneer of high-end second-hand fashion, denounced a toxic promise based on social exploitation, textile waste and the endangerment of an entire industrial ecosystem.

“Fashion for all, misery for a few.” With this slogan, Vestiaire Collective responded to recent Shein’s advertising campaigns, which defended a vision of fashion as a “fundamental right”, affordable for all budgets. According to Vestiaire Collective’s chief impact officer, Dounia Wone in a post on LinkedIn, the real cost of this right is much higher than the price tag: sacrificed local employment, erased textile know-how and a polluted planet. The promise of “democratising” fashion was built on working conditions denounced as abusive.

A seductive economic promise, but unsustainable? Shein conquered the world with a simple formula: thousands of items, updated in real time, at ultra-competitive prices. A dress for 12 euros, delivered in 72 hours, returned if necessary or thrown away. Behind this impressive logistics operation was a model based on a frantic pace of production, up to 75 hours of work per week in workshops denounced by several non-governmental organisations, and a return rate so high that it justified the burial or incineration of unsold new clothes.

Vestiaire Collective directly attacked this logic: “Why should fashion be disposable?” the brand asked in its campaigns. It stated that this model did not include any real costs, neither for the environment, social rights, nor local economies.

Vestiaire Collective, activist and activated

Vestiaire Collective’s attack did not stop at slogans. From 2022, the platform progressively banned more than 70 fast fashion brands, including Shein, Zara, Boohoo, H&M and PrettyLittleThing. This strategy went against the imperatives of volume in e-commerce, but seemed to be paying off. According to the platform, 92 percent of buyers remained active after these decisions, as it banked on the upgrading of the second-hand market.

The company no longer hid that it was now a political player. It actively campaigned for stricter regulation of the textile sector, particularly against Asian fast fashion giants. The anti-fast fashion bill, led by member of parliament Anne-Cécile Violland, which included a bonus-malus system and a limitation on advertising for polluting brands, was in its sights. This bill was buried in March 2025 in a chilling political silence.

Lobbying, appointments and grey areas

The controversy was reignited with the surprise appointment of Christophe Castaner, former minister of the interior, to Shein’s corporate social responsibility strategic committee. For Vestiaire Collective’s co-founder, Fanny Moizant, this was a “national scandal”. She stated that this arrival strangely coincided with the withdrawal of the bill. “Shein was very clever. They defused a regulation that would have cost millions,” she told Madame Figaro.

According to Moizant, France could have become a world leader in the regulation of disposable fashion, and Shein had stopped at nothing to prevent this.

A war of narratives as much as a clash of models

This duel highlighted two antagonistic narratives around consumption: Shein sold speed, novelty and accessibility, at the price of an opaque and controversial industrial model. Vestiaire Collective defended sustainability, quality and circularity, at the price of educating consumers and a profound cultural change.

But this battle was not limited to public statements, it already influenced legislative work.

Law that caused debate

Despite the initial withdrawal of the anti-fast fashion bill, mobilisation continued to put pressure. Under the effect of intense media coverage and growing indignation, the law was revised and put back on the parliamentary agenda, albeit in a watered-down version. While the bonus-malus was retained, the maximum tax was lowered, and advertising restrictions were relaxed. This was a partial victory for advocates of more responsible fashion, but a clear signal that pressure worked.

A sign of the times: leading figures in French fashion were now taking a public stand. From couture houses to independent labels, several industry leaders in turn denounced the Shein model, praised Vestiaire Collective’s courage and called for structural reform. This dynamic could mark a turning point: criticism of ultra-fast low-cost was no longer only voiced by activists, but was becoming an image issue for established players in French fashion.

Shein counter-attacked, French fashion retaliated

As the anti-fast fashion bill approached its examination in the Senate, scheduled for June 10, Shein went on the offensive. Aware of the regulatory threat, the Chinese brand launched a vast advertising campaign signed by Havas, hammering home that “fashion is a right, not a privilege”. This charm offensive was based on the argument of purchasing power, aimed at rallying public opinion against legislation it deemed elitist.

But the French fashion sector was not intimidated. Designers, entrepreneurs, federations and influencers were taking a stand one after the other. Victoire Satto, founder of The Good Goods, summed up the situation: “It’s no coincidence that Shein is communicating so much: it’s scared.” For her part, Fanny Moizant, president of Vestiaire Collective, continued to denounce the destructive economic and environmental impact of the ultra-low-cost model. She reminded people that the law was not intended to make fashion inaccessible, but to restore a competitive balance, while setting clear limits to an industry that was running towards exhaustion.

Yann Rivoallan, president of the French Federation of Women’s Ready-to-Wear, called for immediate action via the DGCCRF (Directorate General for Competition, Consumer Affairs and Fraud Control), citing misleading business practices and illegal promotions.

Jocelyn Meire, founder of FASK and president of the 'École de Production de Confection textile de la Région Sud', also spoke out firmly. He recalled a previous exchange with the president of the Grand Port Maritime de Marseille, who was none other than Shein’s corporate social responsibility advisor, who had described the idea of an environmental penalty on clothing mass-produced in undignified conditions as “disgusting”. Meire reacted with irony and anger: “When clothes become faster than ethics and cheaper than dignity, we’re no longer simply consuming fashion, we’re participating in a collapse.”

At the same time, associations such as 'Les Amis de la Terre', Emmaüs France and WeMove Europe were mobilising citizens and decision-makers. A petition was circulating, opinion pieces were being published one after the other, and a mobilisation was planned for May 14 in Marseille, a city declared “Capital of Eco-responsible Fashion”.

This collective pressure was pushing the legislator to revise its copy: the bill, which had been threatened for a time, was returning to the Senate, in an amended but still ambitious version. Two complementary proposals were sent to senators by the UFIMH and the En Mode Climat collective, in order to avoid any dismantling of the text. For the first time, French fashion was putting up a united front against a global industrial offensive.

Towards a more circular future?

Will the future of fashion lie in second-hand and traceability? Vestiaire Collective was convinced of this. In particular, the company was involved in the development of the Digital Product Passport (DPP), a digital passport that will make it possible to identify a product’s origin, composition and repairability. This technology was supported by the European Commission, and could sustainably transform the textile market by promoting resale, transparency and circularity.

Vestiaire was even envisaging a future where brands would receive a share of resales made on its platform, a new form of sustainable revenue aligned with the circular economy.

At a time when public opinion was polarising around the price of clothing, the battle between Shein and Vestiaire Collective went beyond the simple commercial framework. It questioned our collective priorities: produce more and more for less and less, or consume less, but better?

FashionUnited uses AI language tools to speed up translating (news) articles and proofread the translations to improve the end result. This saves our human journalists time they can spend doing research and writing original articles. Articles translated with the help of AI are checked and edited by a human desk editor prior to going online. If you have questions or comments about this process email us at info@fashionunited.com

This article was translated to English using an AI tool.