The Myth Of The Modern Swing Vote

Who is the heir to Justice Kennedy, if there is any at all? The post The Myth Of The Modern Swing Vote appeared first on Above the Law.

For decades, the gravitational center of the U.S. Supreme Court could be pinpointed to a single seat. Justice Anthony Kennedy famously occupied that role—casting pivotal votes on same-sex marriage, affirmative action, campaign finance, and capital punishment. His jurisprudence wasn’t always consistent, but it was often decisive. With his retirement, and the appointments of Justices Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett, the Court adopted a solid 6–3 conservative majority. Many observers concluded the swing vote had vanished—an artifact of a bygone era of ideological balance.

But the story doesn’t end there.

In this article, I analyze all 104 closely divided Supreme Court decisions from 2020 onward—the Barrett era—each decided by either a 5–4 or 6–3 vote. The question: does a swing justice still exist? If so, who fills that role? And just as critically—does swing behavior depend on the kind of case?

To answer this, I combined full-text analysis of opinions with voting data, legal metadata, and case structure. Using natural language processing alongside doctrinal tagging from the U.S. Supreme Court Database (such as cited constitutional amendments or statutory bases), I clustered decisions not just by linguistic similarity, but by legal substance. These fused clusters revealed distinct issue areas—ranging from Fourth Amendment policing to statutory procedure to ambiguous constitutional rights—each with its own swing dynamics.

With the six conservative justice majority at least two of these justices need to pivot to vote with the three more liberal justices to swing a vote. This means that by definition the notion of a true swing justice is contested. This also means to ascertain a swing justice or justices we need to have a broader perspective than was previously accepted when there were four liberal justices, four conservative justices, and Kennedy who primarily voted along with the conservatives but was most likely to be the swing vote, especially in high profile civil liberties decisions.

What emerged from this analysis wasn’t a Kennedy-style centrist. It was a fragmented map of ideological flexibility. Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Kavanaugh swing frequently, but selectively. Justice Barrett’s influence, once assumed to be rigidly conservative, is quietly increasing—particularly in cases touching on procedural fairness, personal liberty, or the limits of government power.

The result is not one swing vote, but a constellation of issue-specific coalitions. In some areas, the conservative bloc holds firm. In others—especially where dignity, restraint, or individual autonomy are in play—the ideological lines begin to fracture.

This article charts that evolving terrain: not a search for a single median justice, but a deeper attempt to understand how judicial moderation now depends on doctrine, institutional pressure, and legal context.

The Dataset and Methodology

To analyze contemporary swing voting on the U.S. Supreme Court, I assembled a dataset of 104 decisions from the terms beginning in 2020—the period since Justice Amy Coney Barrett joined the Court. Each case was either a 5–4 or 6–3 decision, representing the narrowest outcomes where a single vote could have changed the result.

Each entry in the dataset includes:

- The full text of the Court’s majority opinion

- Individual justice voting positions, coded as “majority,” “dissent,” or not present

- The majority opinion author, an indicator of institutional tone or consensus strategy

- Legal metadata, such as cited statutes, constitutional provisions, and authority types (from the U.S. Supreme Court Database)

- Opinion length, treated as a proxy for legal or cultural importance

Defining a Swing Vote

I located the swing votes as any instance where one of the six conservative justices—Barrett, Kavanaugh, Gorsuch, Alito, Thomas, or Roberts—joined the liberal bloc (Breyer, Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson) to form the majority in a closely divided case.

To ensure the swing is meaningful, I applied two criteria:

- The conservative justice must be in the majority; and

- At least two liberal justices must also be in that majority—indicating a genuine cross-ideological coalition, not incidental overlap.

This operationalization allowed me to isolate not just formal alignments, but moments of ideological movement within the Court’s conservative wing.

Identifying Issue Areas: From Text to Doctrine

Traditional legal datasets assign issue codes that are often too broad or static to capture the shifting terrain of constitutional conflict. To address this, I turned to machine learning—specifically, clustering full opinion texts alongside doctrinal metadata—to infer a more nuanced structure of issue areas.

The process unfolded in two stages:

- Textual Modeling: I vectorized each opinion using TF-IDF, a model that highlights words that are especially distinctive to a document. I then used K-Means clustering to group opinions by linguistic similarity.

- Doctrinal Fusion: I augmented this with structured legal data—including cited constitutional amendments, types of legal authority invoked, and whether precedent was altered or constitutionality challenged. These variables were one-hot encoded and combined with the text vectors to produce fused clusters: data-driven issue areas informed by both language and law.

Cluster Interpretation

The resulting clusters offered rich thematic coherence. After extracting keywords and identifying dominant legal provisions, I labeled each fused cluster. Highlights include:

- Post-Conviction & Habeas Corpus: Procedural challenges to criminal convictions; rights of incarcerated individuals.

- 4th Amendment & Police Powers: Search, seizure, and excessive force; doctrinal boundaries on state enforcement.

- Technical Statutory Disputes: Low-salience or bureaucratic issues often resolved through textualism.

- 1st Amendment & Public Institutions: Expression, association, and the constitutional role of public institutions.

- Residual Liberties & Institutional Tension: Doctrinally unmoored cases involving emergent rights claims, often without clear legal precedent.

Notably, abortion and bodily autonomy cases—once presumed to sit squarely in “civil rights”—appear across multiple clusters, most often in the Police Powers and Residual Liberties clusters, underscoring the fractured nature of contemporary jurisprudence.

With this framework in place, I proceeded to evaluate swing behavior not only by justice, but by legal terrain—using these issue clusters as the primary analytical lens.

Swing Justice Rankings and Patterns

With fused issue areas in place, I turned to the central question: Which conservative justices act as swing votes—and under what conditions?

To answer this, I analyzed each instance where a conservative justice—Roberts, Kavanaugh, Barrett, Gorsuch, Alito, or Thomas—joined at least two liberal colleagues (Breyer, Sotomayor, Kagan, or Jackson) in forming the majority in a 5–4 or 6–3 decision. These are the votes that shift outcomes and signal ideological movement.

The results were clear—and revealing.

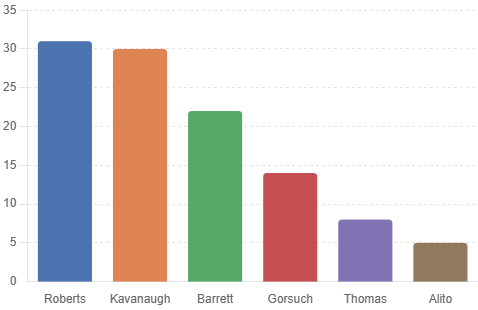

Chief Justice John Roberts was the most frequent swing vote, joining liberal-majority coalitions 31 times. Justice Brett Kavanaugh was close behind with 30 swings, followed by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who broke ranks in 22 decisions. By contrast, Justice Gorsuch did so just 14 times, and Justices Thomas and Alito remained firmly aligned with the conservative bloc, swinging only 8 and 5 times, respectively.

Yet the story deepens when these swings are viewed through the lens of fused issue clusters—a model that integrates both opinion language and legal substance.

Roberts and Kavanaugh were most likely to swing in cases from the “4th Amendment & Police Powers” and “Post-Conviction & Habeas Corpus” clusters—areas involving search, seizure, and criminal procedure, where legal doctrine and legitimacy often intersect. Barrett’s swing behavior also concentrated in these clusters, but extended further into cases coded as “Residual Liberties & Institutional Tension”—a category that includes structurally ambiguous or precedent-sensitive disputes often involving dignity, enforcement boundaries, or procedural fairness.

In contrast, swings were nearly nonexistent in clusters like “Technical Statutory Disputes”, which include administrative law, jurisdictional mechanics, and economic regulation—domains where ideology tends to align with predictable blocs.

This issue-specific variation complicates any effort to identify a single modern swing justice in the mold of Anthony Kennedy. Instead, it reveals a more dynamic pattern: a modular swing role, where different conservative justices moderate in different legal terrains. As the analysis progresses, we test whether this pattern can be predicted systematically—not just observed—using the issue cluster as a stand-in for judicial terrain.

Roberts tends to swing when the institutional credibility of the Court is at stake. Kavanaugh leans toward moderation in cases implicating due process and procedural fairness. Barrett’s swings often reflect a principled concern for liberty, structure, or dignity—especially when the stakes involve the state’s power to coerce.

This is not ideological centrism. It is constitutional strategy.

Civil Rights and the Limits of Ideological Cohesion

If there is a fault line running through the Roberts Court’s conservative bloc, it is most visible in cases involving civil rights and state authority—especially where enforcement power intersects with individual liberty. These tensions are concentrated in the fused clusters labeled “4th Amendment & Police Powers” and “Residual Liberties & Institutional Tension.”

It is in this domain that swing behavior among conservative justices diverges most sharply.

Chief Justice Roberts has often cast pivotal votes in these clusters. So have Justices Kavanaugh and Barrett, whose participation in liberty-reinforcing coalitions has grown in recent terms. In contrast, Justices Thomas and Alito almost never join liberal justices in these domains—highlighting a firm, formalist stance on enforcement and state power.

In Niz-Chavez v. Garland, the majority opinion was written by Justice Gorsuch and joined by Barrett, Thomas, Kagan, Sotomayor, and Breyer. The Court ruled that the government’s use of fragmented notices in removal proceedings violated statutory requirements. As Gorsuch wrote:

“A notice to appear might seem to be just that—a single document containing all the information about an individual’s removal hearing. But as it turns out, the government often serves up that information in a series of smaller bites.”

This case shows Gorsuch and Barrett aligning with the liberal wing on procedural grounds—an outcome shaped not by ideology, but by textual fidelity and due process logic.

In Goldman Sachs Group v. Arkansas Teacher Retirement System, Justice Barrett authored the opinion, joined by Kavanaugh, Roberts, Kagan, and Breyer. The Court scrutinized the class certification process in securities fraud litigation:

“Goldman sought to defeat class certification by rebutting the Basic presumption through evidence that its alleged misrepresentations actually had no impact on its stock price.”

Though framed in financial law, the case reflects Barrett’s concern with procedural legitimacy, a theme that drew swing alignment from both conservative and liberal justices.

In Becerra v. Empire Health Foundation, Justice Kagan, writing for the majority, interpreted a Medicare reimbursement formula and affirmed the Department of Health and Human Services’ broader reading of statutory entitlement. The opinion states:

“The statutory description of that fraction refers to ‘the number of [a] hospital’s patient days’ attributable to low-income patients ‘who (for such days) were entitled to benefits under part A of [Medicare].’”

Barrett joined the majority, along with Thomas, Sotomayor, and Breyer—an ideologically mixed coalition that reinforced the role of textual clarity in high-stakes administrative cases.

Again, the coalition spanned ideological lines, and Barrett’s vote placed her in a camp prioritizing statutory precision and equitable application of federal benefits.

In both Biden v. Missouri and Biden v. Texas, swing coalitions formed on emergency relief and administrative enforcement power. Roberts and Kavanaugh joined liberal justices in allowing the administration to proceed. While the text of the decisions is procedural, the coalition patterns affirm a flexible alignment on questions of federal authority and executive discretion.

What emerges is a modular swing structure—one in which alignment fractures not by ideology, but by issue area.

Roberts swings to preserve institutional legitimacy. Kavanaugh swings when procedural justice is paramount. Barrett increasingly swings when statutory language and enforcement context demand restraint or clarity. These are not centrists in the traditional sense. They are issue-specific swing justices, responding to pressure points in doctrine, structure, and public legitimacy.

In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, Justice Alito declared:

“The Constitution makes no reference to abortion, and no such right is implicitly protected by any constitutional provision…”

Barrett joined that majority in full. But in these civil rights cases—where bodily autonomy, procedural fairness, or state coercion are at stake—her voting pattern has often moved closer to the Court’s center.

The swing vote, then, no longer resides in a single conscience. It fractures by issue area, forged through doctrine rather than ideology, and anchored not in compromise but in distinct judicial philosophies.

A Predictive Model of the Swing Vote

To test whether swing voting behavior can be predicted—not just observed—I trained a series of statistical models using the fused issue clusters as inputs. These clusters integrate both the semantic content of opinions and their doctrinal structure, offering a richer representation of the legal terrain.

The goal was straightforward: could knowing the issue area of a case predict whether a conservative justice would break ranks?

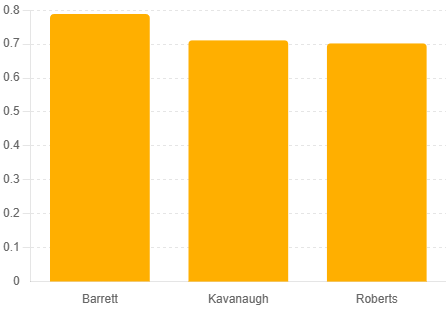

I tested three justices: Roberts, Kavanaugh, and Barrett—each a key figure in contemporary swing behavior.

Using logistic regression, I modeled each justice’s swing status as the outcome (1 if the justice joined the liberal bloc in a 5–4 or 6–3 majority, 0 otherwise), and the issue cluster as the sole input. The models were evaluated using five-fold cross-validation.

The results:

- Barrett: 78.9% accuracy

- Kavanaugh: 71.1% accuracy

- Roberts: 70.2% accuracy

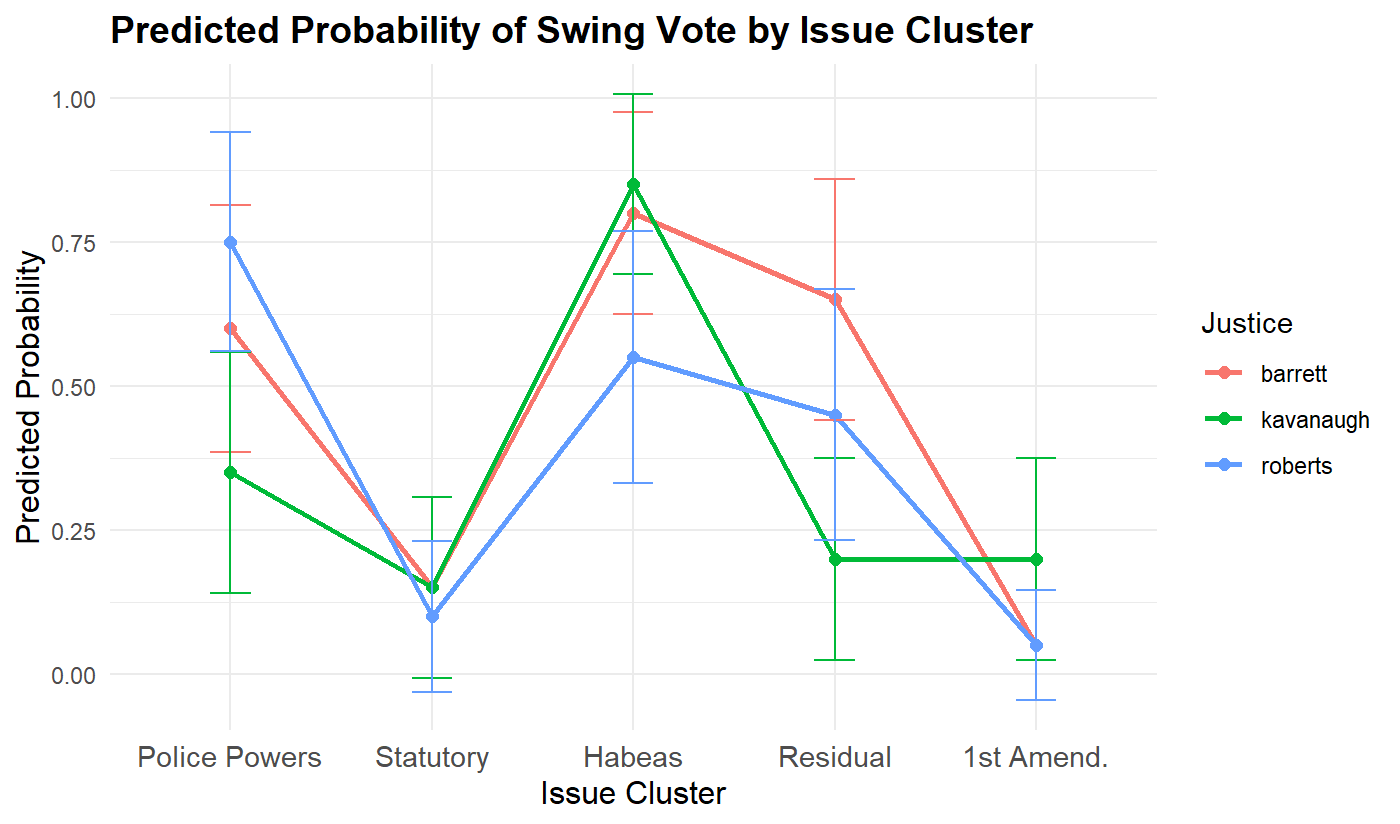

To visualize how legal context shapes swing behavior, I plotted the predicted probabilities from each justice’s logistic regression model across the fused issue clusters. The chart shows how likely each justice—Roberts, Kavanaugh, and Barrett—is to swing in each legal domain, based solely on the issue area of the case.

These predictions confirm that swing behavior is not random—it is systematically shaped by issue area. In fused clusters like 4th Amendment & Police Powers, Post-Conviction & Habeas Corpus, and Residual Liberties, the model assigns high swing probabilities to justices like Barrett and Roberts. In contrast, issue areas involving economic regulation, technical statutes, or immigration enforcement yield predicted probabilities close to zero—indicating near-total bloc alignment.

These probability trends reinforce the core finding: different justices swing in different legal terrains, and those terrains can be modeled.

One Swing Justice, or Many?

To clarify the dynamics further, I tested two competing frameworks:

- Single Swing Justice Model

Treats Roberts as the definitive swing vote across all cases. - Issue-Specific Swing Model

Allows the identity of the swing justice to vary by cluster—e.g., Barrett on civil rights, Kavanaugh on criminal procedure.

The data overwhelmingly favors the second model.

While Roberts remains the most institutionally consistent swing voter, Barrett’s predictive model was the strongest, with nearly 79% accuracy. Her swing behavior correlates most with cases involving state enforcement limits and constitutional restraint. Kavanaugh’s swings, meanwhile, align more closely with procedural fairness and criminal process protections.

This pattern reflects a dispersed architecture of swing influence. The swing vote today is not a single seat—it is a modular role, activated differently depending on the issue area, legal frame, and institutional stakes.

What was once a matter of median ideology is now a function of doctrinal pressure and judicial logic—and that shift can be measured.

Barrett and the Long View

The quantitative and case-level analyses converge on a central insight: Justice Barrett’s swing behavior, though less frequent than Roberts or Kavanaugh, is the most systematically tied to the nature of the case. While Chief Justice Roberts often garners attention as the Supreme Court’s institutional swing vote, the data reveals a quieter but consequential evolution: Justice Amy Coney Barrett is emerging as a swing vote in key domains—particularly those involving enforcement power, procedural fairness, and statutory interpretation.

Since joining the Court in 2020, Barrett has aligned with liberal justices in multiple closely divided decisions. Her swing behavior concentrates in issue areas defined by constraint and clarity: the 4th Amendment & Police Powers and Post-Conviction & Habeas Corpus clusters. Her votes in these domains don’t signal ideological drift but reflect a jurisprudence rooted in textual rigor and structural restraint.

In Van Buren v. United States (2020), Barrett authored the opinion limiting how prosecutors may use the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. Emphasizing statutory boundaries, she wrote:

“It does not cover those who, like Van Buren, have improper motives for obtaining information that is otherwise available to them.”

Here, Barrett narrowed the government’s power to prosecute access violations based solely on motive—underscoring her view that liberty must be protected by precision in statutory construction.

While Goldman Sachs arose from financial regulation, Barrett’s opinion reveals her procedural formalism—her swing votes often hinge not on policy outcomes, but on statutory precision and burden of proof. Her reasoning in that case reflects a focus on burden of proof and the procedural rights of defendants, even in high-stakes economic contexts.

Perhaps most telling is her participation in Lombardo v. City of St. Louis (2020), a Fourth Amendment case concerning excessive force. Barrett joined a per curiam majority alongside Kavanaugh, Roberts, Kagan, Breyer, and Sotomayor that vacated a summary judgment in favor of law enforcement: “The three officers brought Gilbert, who was 5’3” and 160 pounds, down to a kneeling position over a concrete bench in the cell and handcuffed his arms behind his back… Emergency medical services personnel were phoned for assistance.”

By remanding the case, the Court signaled concern that lower courts had failed to fully consider whether the officers’ force was excessive under the Constitution.

Barrett’s swing votes do not appear driven by ideology—they are rooted in textual discipline, a willingness to reconsider enforcement practices, and a procedural sensibility that sometimes leads her to coalition with the Court’s liberal wing. She is not a centrist in the Kennedy mold. But she is increasingly a structural voice for constraint—especially when liberty, enforcement, and precision intersect.

The Fragmentation of Swing Power

If the Roberts Court has a swing vote, it doesn’t belong to one justice. It belongs to a pattern—and increasingly, to a map of issue-dependent alignments.

Across the 104 closely divided cases, Chief Justice Roberts remains the most frequent swing voter. But his influence is no longer universal—it is situational, shaped by questions of institutional credibility and precedent. Justice Kavanaugh is nearly as likely to swing, particularly in cases involving procedural fairness or criminal law. And Justice Barrett, while swinging less frequently overall, shows the clearest directional shift: a rising presence in clusters where state power, enforcement boundaries, and constitutional dignity are contested.

This reflects not the death of the swing vote—but its transformation. The era of a single ideological median, epitomized by Justice Kennedy, has given way to a modular model: different conservative justices swing in different legal terrains, guided by distinct judicial logics.

Kennedy’s swing votes spanned doctrines and decades. His role was personal, often framed in the language of dignity and individual autonomy. But today’s Court does not hinge on personality. It hinges on terrain.

- Roberts swings where institutional legitimacy is at stake—especially in administrative law, precedent-sensitive disputes, and interbranch tension.

- Kavanaugh swings when procedural integrity comes to the foreground—cases involving arrest process, prosecution, or due process claims.

- Barrett swings in domains of constitutional restraint—where liberty and dignity intersect with enforcement, and where doctrinal clarity can limit state power without signaling ideological compromise.

This fragmentation has both doctrinal and predictive consequences.

It means that counting votes is no longer enough. Understanding outcomes requires reading the opinion structure—who authored it, who joined it, and how the majority reasoned. Swing votes now cluster around specific legal questions: Fourth Amendment seizures, death penalty reviews, procedural habeas, and administrative removal power.

It also shifts how we forecast the Court. Ideological orientation alone is not predictive. The strongest models—like those used here—show that swing behavior is best understood through fused issue clustering. The probability of a swing can be forecast based on legal context, not political identity. Barrett, for example, is the most predictable swing vote by cluster. Roberts is more frequent but less modelable. Kavanaugh falls in between.

In this sense, the swing vote has not disappeared. It has dispersed—across justices, across issue clusters, and across a Court that no longer speaks in consensus, but in coordinated, fractured alignment.

And that, too, is a signal—not of ideological unity, but of judicial structure under pressure.

Adam Feldman runs the litigation consulting company Optimized Legal Solutions LLC. Check out more of his writing at Legalytics and Empirical SCOTUS. For more information, write Adam at adam@feldmannet.com. Find him on Twitter: @AdamSFeldman.

The post The Myth Of The Modern Swing Vote appeared first on Above the Law.