Honey, wake up: mead abuzz with a new lease of life

Forget everything you thought you knew about mead — Gosnells is rewriting the rules. Light, sparkling and refreshingly modern, it’s a bold new take on an ancient drink, writes Declan Ryder. The post Honey, wake up: mead abuzz with a new lease of life appeared first on The Drinks Business.

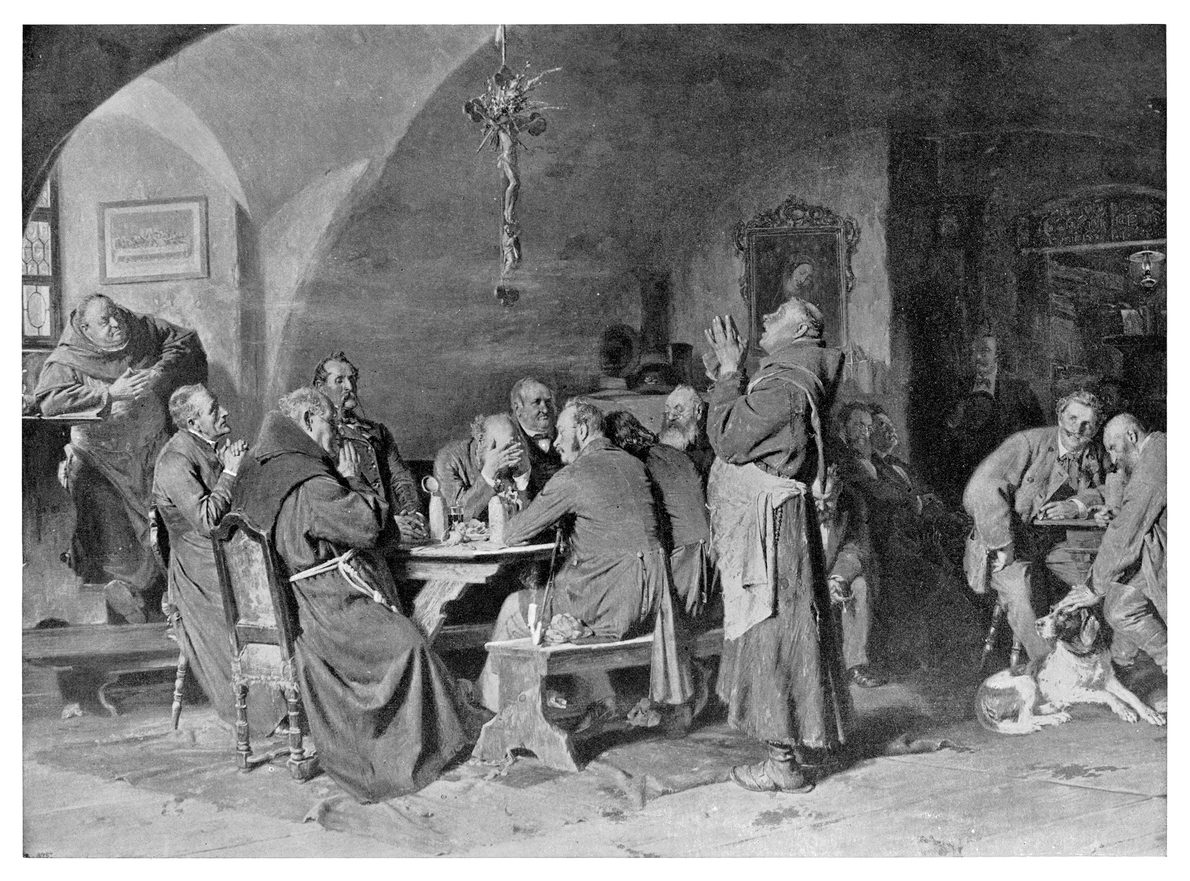

Most of us know mead as the forgotten medieval tipple that faded into complete insignificance centuries ago. It is discussed in conversation much in the same light as other now obsolete relics like trebuchets and chamber pots. Though once relegated to obscurity around the Renaissance, mead has enjoyed a mini renaissance of its own in the past 10-20 years, moving out of the history books and back onto the palettes.

The mead industry was declared the fastest-growing drinks category in the US in 2017. There are now around 250 meaderies across the pond – a figure that only increases year on year. And globally, the appetite is increasing too: Fortune Business Insights projects the global market to grow from US$591.5 million in 2024 to US$1,395.7 million by 2032, at an annual growth rate of 11.33%.

But while many hail this as a great revival, Tom Gosnell, founder of one of the UK’s leading meaderies, sees things very differently.

“I haven’t seen a resurgence of mead, at least in the UK,” he says. “There’s not that many producers, and they’re all quite small.”

This is the tension at the heart of mead’s modern moment: it may be the world’s oldest alcoholic drink, but its future may depend on forgetting its past.

Most of us know mead as the forgotten medieval tipple that faded into complete insignificance centuries ago. It is discussed in conversation much in the same light as other now obsolete relics like trebuchets and chamber pots. Though once relegated to obscurity around the Renaissance, mead has enjoyed a mini renaissance of its own in the past 10-20 years, moving out of the history books and back onto the palettes.

The mead industry was declared the fastest-growing drinks category in the US in 2017. There are now around 250 meaderies across the pond – a figure that only increases year on year. And globally, the appetite is increasing too: Fortune Business Insights projects the global market to grow from US$591.5 million in 2024 to US$1,395.7 million by 2032, at an annual growth rate of 11.33%.

But while many hail this as a great revival, Tom Gosnell, founder of one of the UK’s leading meaderies, sees things very differently.

“I haven’t seen a resurgence of mead, at least in the UK,” he says. “There’s not that many producers, and they’re all quite small.”

This is the tension at the heart of mead’s modern moment: it may be the world’s oldest alcoholic drink, but its future may depend on forgetting its past.

![[Podcast] Behind the Breakthroughs: How Almac Powers Clinical Trial Success with Care](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/5lAJkli_KcGt1FSsw4EaegjgP76IHREqYEWbhNBJOXw/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9CaW9QaGFybWFEaXZlXzEzNDZfeF83MjlfQXJ0d29yay5qcGc=.webp)

.jpg)